A Pocket Canon to Shrink the World

How to Get Along via "Middling Content"

I set a goal at the beginning of this year to complete a draft of a book I’d been toying with for a few years, and those of us with paper calendars can see the pages getting mighty thin.

The book will be a manual to help people make the most of their media experiences in a media environment that is growing increasingly hostile to healthy human functioning. In it, I’m consolidating my experience doing research with major advertising platforms like Google and Facebook, analysis for major creative studios like Disney and Sony, and my personal exploration of global media traditions in a half-dozen trips around the world. I hope it’ll be useful to others, but at the very least I am confident it will be helpful to me as I map out my 2026.

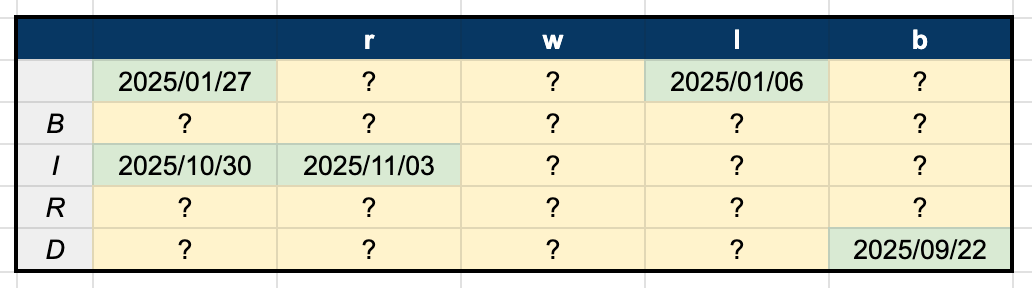

I am using the above 5x5 matrix to track the components; I’ll share more about this matrix in an upcoming post.

The “Middling Content” of Middling Content

Just as Frankenstein isn’t the monster and Jaws isn’t the shark, the content I write in Middling Content isn’t itself “middling content”. True “middling content” spans large audiences and provides a common reference point through which human beings can connect with each other. The 80-song playlist was a helpful exercise for me, but it takes a few hours to listen to completely1. What if you want to middle in a more short-form and convenient way? What could be a tool to facilitate this, almost like the Babel Fish in The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy, but for narratives instead of languages?

In trying to facilitate communication and understanding in broad global contexts, I’ve assembled what I consider my “pocket canon”: a short list of passages that I personally have found meaningful from distinct yet populous traditions of thought. I have specifically tried to identify passages that complement each other and my own passions, so that I can continue to deepen my understanding of them without straying too far outside my normal life and goals.

In today’s newsletter, I’m going to talk through a few key points:

an overview of modern western history

my four passages that represent over 7 billion people globally

how I knit those four passages together

how you might create your own “pocket canon”

But first: a quick disclaimer.

A Quick Disclaimer!

I’m going to talk about texts that are literally sacred to people.

In all of world culture and human history, religion is one of the most beautiful, spiritually deep and intellectually enriching aspects of our species. And yet, it also incites terrible and horrific violence. People have been killed for liking sacred texts, killed for disliking sacred texts and killed for minor deviations in interpreting sacred texts.

I don’t want that. I want the opposite of that. I think a lot of human conflict boils down to misunderstandings and semantics. I am approaching from a place of genuine adoration and curiosity.

As a part of trying to be respectful to the texts I’m discussing, here are four disclosures that hopefully communicate my entering this conversation in good faith.

My Knowledge Is Limited. While I’ve been working through these texts for years (and in some cases decades), I am not trying to crowd out other deeper expertise and experience. Indeed, I’m trying to do the opposite and I hope that with more conversations my thinking will continue to evolve. My goal is to provide a broad-based yet simple textual foundation for a global society, and I believe being open about this process will allow me to improve and document what I learn so others can benefit.

Intentions Matter. If you want to use a structure like this to spark conversation, it does require some level of tact. My success in using this “pocket world canon” to enter into conversations with people around the world has been because I balance genuine adoration and curiosity. And I think both elements are needed together. If you are just passionate about the text but inflexible in your interpretation, you can find yourself starting a fight. If you are inquisitive but haven’t spent any time or work investigating independently, your inquiry can be burdensome. But in balance, appreciation and curiosity can allow you to use these passages to build common ground and grow relationships across lines of difference.

Text Inclusivity Is Essential. I’ve deliberately selected texts that resonate on a purely humanist level for those who don’t identify with any religious tradition. I also think they can reflect on each other in case you identify exclusively with one of these traditions. I know many people have had negative experiences with religion, and that will certainly make it harder to see anything positive in a religious text.2 I still hope that by selecting texts that are meaningful to billions of people, that there might be an opportunity for creating connection and value. But it’s okay to skip parts that aren’t for you at this moment.

Exclusion Doesn’t Signify Dismissal. I do not consider my “pocket canon” the optimal “pocket canon” for everyone. I expect it may even evolve for me as I continue to read and learn. I understand that it overlooks many important narratives and people groups globally, and that is not to be taken as diminishment of those narratives and people groups. Indeed, having a “pocket canon” hopefully facilitates branching out into these traditions as well. Having a core foundation helps integrate and retain new information.

If you see anything in here that doesn’t look or seem right to you, please reach out and let me know as I can continue to revise this! Though I’m keenly aware of the maxim “all models are wrong, some models are useful”, I do still aspire to

With that out of the way: let’s talk about knitting!

Generations Simplified: Knittings & Splittings

Before the word “millennial” was co-opted by the marketing industry, it was coined as a part of a generational theory created by playwright William Strauss & policy consultant Neil Howe. Their deeply detailed “Strauss-Howe Generational Theory” has four types of generations and four corresponding cycles that combine into what they call a “turning”. Essentially, a “turning” is a roughly 100-year process through which a stable society collapses and rebuilds in its own ashes; there are four cycles between the American Revolution and the Civil War, and another four cycles between the Civil War and World War II.

Rather than getting lost in the weeds of learning all of this, I like to simplify it into an alternating pattern between “knitting” and “splitting” that is less caught up with birth year, which seems to be useful mainly in applying generational segments in marketing contexts. History tends to have two kinds of critical figures: “knitters” who unite disparate peoples into a greater whole and “splitters” who disturb an unjust consensus. Usually the knitters whose coalitions persist will be viewed favorably by historians like Alexander the Great, Sukarno and Yu the Engineer; figures whose coalitions don’t last, like Genghis Khan and Napoleon Bonaparte, have a more mixed consensus. Similarly, the splitters whose divisions are permanent, like George Washington and Simón Bolivar, are viewed more favorably than those who fail to make a lasting impact on the map.

Because Middling Content is a humanist project, we tend to be more interested in the “knittings”; specifically, we are interested in the “knitters” who use media and culture to unite rather than divide through fear or violence, and we are interested in ways to knit the knittings together to an even broader human consensus.

The Strauss & Howe Generational framework is specifically a framework for thinking about “The West” in particular. You already have some intuition of their system if you’ve used the phrase “Generation Z”. Strauss & Howe start their generational framework with the “Arthurian Generation”, which includes the explorers that brought Europe into contact with the New World. Because “Z” is the 26th letter, “Gen Z” is the 26th generational season3. But of course, over three-quarters of the world’s population exists outside this framework.4

The goal here is to find four texts that each cover roughly a quarter of the world’s population. And to do this, we’ll begin our history not around the sixteenth century’s age of protestant reformation, but instead to an earlier reformation a couple short millennia earlier.

I.) Reformation & Self-Help in ~544 BC

When trying to create a “pocket canon” to fit the thinking of the world’s people, an easy way to start is to look at a list of the most populous countries, and at the top of that list is the country where our first text is sourced.

The largest country in the world as of April 2023, India is home to over a billion practitioners of Hinduism (or, to some, “Sanātana Dharma”), with another 200 million abroad. And the traditions within the practice are expansive enough that they substantially overlap with other major practices -- and finding a text that is both in conversation with Hinduism but also groups in the 400 million followers of Buddhism in countries like China (244M), Thailand (64M), Japan (46M) and Myanmar (38M) will give a key to conversation with over 1.6 billion humans.5

Though many Buddhists will practice and study Buddhism separate from the other traditions that influenced it, the Buddha draws from Vedic concepts in core Hindu texts like the Upanishads. And even though he deviated from some core Hindu ideas, much of his thinking was later incorporated into broader Indian culture; Ashoka, a ruler of the Maurya Empire that spanned the Indian Subcontinent, was a major patron of Buddhism, and as a consequence, many practitioners of Hinduism today still consider this text significant. (Some of this may even not be religiously motivated but simply a fact that any primary source from Buddha is at the very least relevant as a piece of India’s intellectual history and development.)

My personal favorite text that knits together the large and disparate Hindu and Buddhist communities is one I spoke about last week in my October tax reflection: the Dhammacakkapavattana. It’s the first sermon given by Siddhartha Gautama after his enlightenment, and is associated with Sarnath, just north of the holy city of Varanasi6. I actually have visited where this speech allegedly took place!

I prefer to refer to it by its Pali pronunciation7, because that was the language the Buddha used to deliver it -- and also because it avoids the dreaded “r” sound that outs foreign language speakers in basically every region of the planet. But the Sanskrit name will have more familiarity to yoga practitioners and/or viewers of the LOST television series: the Dharma Chakra Pavartana. The use of concepts like “dharma” and “chakra” are just another way that the text fits not just within the Buddhist canon but also in the broader South Asian philosophical history.

This ~800-word text has Buddha’s greatest hits like “the middle way” and “the four noble truths”, but personally I ground my thinking with the 54 words near the end where he outlines his befamed “eight-fold path”.

What is that middle way of practice?

It is simply this noble eightfold path, that is:

right view, right thought,

right speech, right action, right livelihood,

right effort, right mindfulness, and right immersion.

This is that middle way of practice, which gives vision and knowledge,

and leads to peace, direct knowledge, awakening, and extinguishment.

The translation above is from Sutta Central, which I’ve enjoyed using for my study of Buddhist texts because they will provide the Pali transliterations; because this was an aural tradition before it was a written tradition, I enjoy hearing the rhythm of the words and consonants.

Eight steps are manageable on their own, but every consultant knows a process should have three steps; and indeed, the Buddhists are good consultants -- centering the problem (suffering/pain) and providing a three-step framework to abstract over the more granular/technical resolution. I found it helpful to use a common distillation of the eight steps into three categories8: panna (wisdom), sila (virtue) and samadhi9 (immersion). This breakdown also becomes more relevant as I talk about synthesizing these passages later on.

II.) The Wind & the Water

Again, to find a large intellectual movement, it can help to find a large nation-state; the other 1.4 billion-person population powerhouse China also has deep roots for its intellectual history. The three major philosophies in Ancient China all relate to orienting the self within a broader system: Confucianism focuses the social order, Legalism focuses on the political order and Daoism focuses on the natural order.

Of these three, Confucianism is probably most discussed both in and outside of China, but I think despite Wikipedia’s estimate of a population of only 12 to 173 million Daoists that it is a school of thinking with broad applicability and relevance. Just as Buddhism was grounded in a validatable study of the psychological/psychic world within us, Daoism was grounded in a study of the physical world around us. To study “the Dao” is to study the way the world operates and develop life practices within that. In this way, one can see it as similar to the study of physics or “design thinking”.

For example: consider the Daoist practice of “fengshui”. To those who don’t speak Chinese, the name can sound exotic and perhaps mystical, but the truth is much more practical and empirical. Translating to “wind and water”, it explores a kind of broad fluid dynamics within nature. It is a study of flows. One can see gravity and electromagnetism within a Daoist concept of the universe. Mainland China’s CCP could be seen as believing in a historical “dao” or path, an innate Marxian entropy to the universe that eats away at wealth inequality and elevates the working class. There are crackpot Daoists just as there are crackpot scientists and crackpot economists, but the goal is to identify the hidden springs that move the world. If you include naturalistic atheists and scientists/engineers into a sort of Greater Daoism, this group likely draws on at least 2 billion of the world’s population.

By using a Daoist text to reflect this perspective, I do not mean to suggest China is the only region of the world analyzing the flows and tendencies of the universe. There are many others, and I don’t mean to claim Daoism is the first of these practices either. What Daoist texts do, though, is connect you with over 1.4 billion residents of Greater China. And it is a school of thinking that came into the world with some truly beautiful poetry.

The Dao de Jing is the first and core text of Daoism; written by the father of Daoism Lao Zi, its brevity makes it an easy access point to the way of thinking. When I was in my mid-twenties, I would ask my Alexa10 to read it to me when I wanted to fall asleep. Essentially 81 short poems, it can be read in its entirety in under an hour. But its sparse and metaphorical style means translations run the gamut, and the reading and re-reading of passages can be a deeply satisfying process.11

The passage I use in my “Pocket Canon” from the Dao De Jing is Chapter 28.

Know strength, yet remain yielding;

Through this flow, excellence is unending and rejuvenating

Know truth, yet remain open-minded;

Through this system, excellence is unfailing and expanding.

Know right, yet remain humble;

Through this path, excellence is sufficient and sustainable.

The wise govern with simple splits;

The best rules never divide.

This above translation is my own, influenced by the Chinese Text Project, which has a variety of key Daoist and Confucian texts; in particular, I like how they have implemented tooltips for fast character-by-character translations, which allows for a more direct reading of the original text. (The translated lines they provide for the Dao de Jing in particular force a rhyme scheme that distorts the meaning and makes the passage too verbose, in my opinion. But it can still be interesting as an alternative! And I love rhymes!)

Though this passage does not explicitly mention the famous yinyang (literally: dark-light), we see how Daoism both elevates and rejects binaries.12 The xióng/cí binary (strength/yielding) reflects on gender and power; the truth/ignorance binary reflects on knowledge; and the righteous/humility binary reflects on virtue.

And even as we move west and into the new millennium, we still find a continuation of this struggle for balance.

III.) SparkNotes from a Street Magician

The latter two texts in my “Pocket Canon” hit the two billion mark pretty easily, though it’s still useful to break down. Wikipedia suggests that the world has 2.3 billion Christians, for whom their sacred text would be the Bible. This large number does somewhat mask variance in a couple ways: (1) there are various denominations within the ~1.3 billion Catholics, ~700 million Protestants and ~300 million Eastern Orthodox and (2) of all the texts discussed so far, the Bible is consumed almost exclusively in local languages through translations that can vary considerably.

I was raised Catholic, which means the Bible is the text I’ve spent the most time thinking about; it also means I was not raised with the text in the same way as friends of mine raised Protestant. I do still tend toward the Catholic belief that meaning resides not within text itself but within communities. While I don’t currently attend Mass, I received my first communion, was confirmed, and even considered becoming a priest. Part of what sparked my prioritizing writing my thoughts out was a conversation about Catholicism with my grandfather in June 2019 where he said I ought to write this stuff.13 This exercise requires me to be a bit more textually-centered, though, so it’s still a bit outside my primary context.

While we don’t know much about the childhood of Jesus Christ14, the Gospel documents that he moved at least twice -- from Bethlehem to Egypt and then later to Nazareth. Using the historical context of his time, though, we can make a few educated speculations.

A Few Educated Speculations

Since the city with the largest Jewish expat community at the time would have been Alexandria, there’s a good chance that’s the unspecified Egyptian city where the Holy Family relocated post-Bethlehem and where young Jesus grew up.

Since Alexandria was famous for having the largest library in the world, it would have been a likely place where knowledge from the rest of the world would be stored.

Since Alexander the Great made it as far as the Nanda Empire15 in 323 BC, some knowledge of Buddhism is likely to have made it back into his empire by the times of Jesus centuries later.

Since the Silk Road that connected Chinese and Roman empires started in 30 BCE when Rome conquered Egypt, it also seems reasonable to expect core Chinese literature and ideas would be represented in a knowledge center like Alexandria.

Putting these together, it feels highly feasible and even likely that Jesus had exposure during his childhood to ideas from the traditions we’ve already discussed. Turn-of-the-Millennium Alexandria would have been an extraordinarily diverse place, drawing on a variety of traditions from Africa, Europe and Asia.

Some go further and theorize about a Beatles-esque “Jesus in India” period, which would of course provide him even more exposure to broader thought, but to me that starts taking unfalsifiable leaps of faith. Even just using consensus text, I think we can infer that young Jesus was a “third culture kid” who had exposure to a wider range of ideas than his peers by the time he returns to Jerusalem. And this insight helps us make meaning of our next text.

The Bible focuses on Christ’s life between the ages of 29 and 33. As an adult back in Jerusalem, Jesus was a part of a broader movement within the Roman empire of itinerant preachers who would create spectacles to draw attention to their message. And my go-to passage is Christ’s own simplified expression of his religious perspective when asked.

Three of the four Gospels share the interaction. Let’s cover it in Matthew 22:35-40, because I like the phrasing there the most.

One of them, an expert in the law, tested him with this question:

“Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?”

Jesus replied:

“‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’

This is the first and greatest commandment.

And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’

All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

I’m using the NIV Translation above through Bible Gateway, which provides word-for-word translations in Greek or Hebrew for New and Old Testaments respectively. This “godly love” and “neighborly love” binary is reminiscent of the binaries found in Dao De Jing 28, though the layers of translation and interpretation can make it tricky to interpret. The “neighborly love” directive comes across as intuitive to most people, but the “godly love” directive has more theological weight to it.

In particular, the word “God” can trip some folks up; it is genuinely a bit odd that English speakers use the word “God” when the word doesn’t appear in any of the four languages Jesus is believed to have spoken. As we discussed earlier, Buddhist texts don’t translate key terms like “dharma” or “chakra”; Daoist texts retain key terms like “fengshui” or “wuwei”. But in the spread of Christianity, those speaking Greek and Latin would use the terms “Theos” and “Deus”, which share etymology with words for “day” since the sun was a critical deity. (And these terms carry into other Romance languages with the Spanish “Dios” or the French “Dieu”.) Slavic language speakers pray to “Bóg”, the name of the pagan deity at the center of their pantheon. In Indonesia, the Christian deity is called “Allah” because Islam spread to the island nation before Christianity did.

The word “God” is perhaps the weirdest of the bunch, though, because it’s the central deity for the Gothic peoples who were responsible for the sack of Rome in 410. So to pray to “God” is in a way to pray to Christianity’s greatest enemy. Due to the lack of written material, it’s hard to know what the Gothic peoples named themselves after, but one theory is that the term evolved from the name of the river where they originated (also the namesake of the city of Gothenburg). The idea of God-as-stream feels very Daoist and also consistent with the Greco-Roman God-as-sun etymology; these are etymologies that fit the Judeo-Christian model of thinkers like Newton and Spinoza who considered God deeply intertwined within nature itself.

Read this way, the primary directive is to love “the forces of the world”, to love nature and to love life itself. It’s to love “the flow” or to love “beingness”. It’s to love that the world exists.16 It’s a more internal project that contrasts with the external project of neighborly love.

This internal/external divide has parallels with the texts we’ve already discussed: Buddhism’s external virtue (sīla) and internal meditation (samadhi) or Daoism’s external strength (xióng) and internal yielding (cí). And similar to how these other texts created a portable framework that individuals can apply, this gloss functions as a sort of secret decoder ring through which all prior moral instruction can be read. In programming, we call this “refactoring”; this new framework takes a large codebase and expresses it more succinctly and elegantly. While it’s considered more “miraculous” that he conjured merely two fish into hundreds to serve his followers a feast, it was by reducing hundreds of commandments down to merely two that he most served his followers.

And there’s more active/passive duality expressed again in our final text.

IV.) Meditation on a Sunset

Our final major text draws on two billion readers to bring our canon’s coverage of the human population around 7.4 billion people (89%, solid B+ work). I’m not sure a text has changed the face of the earth as rapidly as the Quran. Completed in 632, the book’s followers would take less than a century to cross the northern coast of Africa and into Europe to become a tri-continental Umayyad Caliphate by 711.

The linguistic context in which the Quran is read is unique in that its sacred language is among the most spoken in the world. It is rare for readers of Dhammacakkapavattana to be able to speak Pali, and though it’s most common to read the Dao de Jing in Traditional Chinese characters with Mandarin pronunciation, it was originally in an old, now-unused version of spoken Chinese that is uncreatively called “Old Chinese”. There is a minority of Christians who speak Modern Greek, but this is not mutually intelligible with the Koine Greek of the New Testament; and, as touched on earlier, Christ’s quotations written in Greek were likely spoken in Aramaic or Hebrew, and the specific phrasings/diction is lost-to-time and -in-translation. MSA or Modern Standard Arabic was deliberately constructed to retain classical elements of Quranic Arabic to maintain comprehensibility against forces of linguistic entropy.

And on the topic of entropy, it is maybe fitting that the final of the four texts in my “Pocket Canon” is in some sense about the decline of the afternoon sun in the sky. And who doesn’t love a sunset?

Surah 103 is one of the shortest in the Quran, and I find it an accessible point to start thinking about the Quran because it’s light on abstract cosmology and metaphysics. The cosmology/metaphysics is really limited to the Sun, which is a pretty universal and accessible point of human experience. The “Asr” is the name of the third prayer time, which generally is considered to start when the sun is halfway between noon and setting. (So it’s about the buildup to sunset rather than the setting itself.) The surah opens with this “Al-Asr”, and its opening line also serves as its title, like an Emily Dickinson poem.

At the end of the day, everyone is lost,

except those who see clearly and do good

and those who help others see clearly and be patient

This is my own translation, which I created with the assistance of Quran.com which provides word-by-word translation. While I’ve shouted specific sites for each text, I’ve found that the Quran has dozens of high-quality websites and applications, perhaps because it is a more standard practice in Quranic study to try to capture original intent and meaning of specific terms. These sites are some of the best user experiences I’ve ever had reading a text in another language; providing word-level translations, line-level translations, pronunciation audio and even the correct singing of each word. While I don’t pick favorite texts within the “pocket canon”, because I see the texts within conversation with each other, I also must acknowledge superior website design when I see it.

There are echoes of our other texts here.

Similar to the Buddha’s Dhammacakkapavattana, we see that Muhammad opens this Surah by framing the problem: “lostness”, which is a kind of disconnectedness, alienation, depression, suffering. And Muhammad, like Buddha, prescribes a path as well, though this one only has four steps. And it too begins with view and ends with supporting a sort of meditation/mediation.

As we found with the Dao De Jing, we see binaries in this four-step path. We have a division between the self (1 & 2) and the community (3 & 4), and there’s also a division between internal truth-seeking (1 & 3) and external action (2 & 4). The internal/external binary most closely maps to the binaries we explored in Chapter 28.

It’s unsurprising that we would find overlap with Christian doctrine since Jesus (“Isa ibn Maryam”) is in the Quran, but the parallels are worth noting. As we found with Christ’s distilled commandments, there is a godliness and neighborliness element. What I’ve translated here as “see clearly” is more often translated as “believe”; the word in Arabic is “aminu”, which Catholics will recognize as a close cousin of our common refrain “amen”.17

Lastly, I’ll just add that there’s also a sort of force of history I read into this text. I mentioned already the speed of Islam’s spread in the 7th Century, with the westward expansion serving as a kind of original manifest destiny; Northeastern Africa in Arabic is referred to as the Maghreb -- literally “sunset”. (Reflecting this concept back, Westerners will refer to parts of the Middle East as the “Levant”, which refers to the sunrise.) And I think the sun-chasing idea is powerful in “the West” at large. After the Umayyad Caliphate chases the sunset all the way to Spain, they occupy18 the territory for nearly 800 years; then in 1492, the same year the Muslim rule ended in Spain, the Spanish then carry the torch in the sunset-chasing conquest relay further West still into the New World.

As we follow the sun around the world a couple hundred thousand times, we find ourselves back in the present.

And so how in this moment might you make a framework like this? And how will this framework inform future writing here?

Assembling & Activating a Pocket Canon

As mentioned earlier, I don’t think everyone needs the same shortlist of cultural shortcuts to create common ground with the world’s population. If you’re trying to create your own “pocket canon”, LLMs have put us in a golden age of text-analysis tools that make it easier than ever to find parts of a text that could be meaningful to you. If you use a chatbot often, you could even just deliver a prompt: “based on what you know about me, what passage or quote from [text/tradition] do you think would resonate with me?”19 This allows you to make most of your reading grounded in primary sources with real human authors, but you’re just using the LLM to help find a suitable place to begin.

I think of this task as similar to peeling an orange in a single rind20. Before you start to peel, you want to examine the orange and find the right place to start, because this makes all the difference. If a passage doesn’t resonate with you at all from the get-go, it’s probably not the passage for you!

For me, it’s probably no coincidence that these texts all are applicable to media theory, the subject of this newsletter. The acts of producing and consuming media match these binaries: media production aligns with the action of Daoism’s xióng, Buddhism’s sīla, Christianity’s ahavta-rea & Islam’s amilu; meanwhile, media consumption aligns with the acceptance of Daoism’s cí, Buddhism’s samadhi, Christianity’s ahavta-Elohim & Islam’s aminu. Most academic media research21 I’ve read seems to center on pragmatic questions around messaging (either in the context of state propaganda and private marketing), but since my focus is wellbeing and the good life, religious texts and doctrine provide a more humanistic foundation.

For those still resistant to the use of religious frameworks in this way, it may be of some comfort that I also draw on the psychological frameworks of Freud, who considered all religion a “universal compulsive neurosis”. I find a lot of value in the writing of his school of thought on Lebenstrieb and Todestrieb -- the life drive that pushes us to act and the death drive that pulls us into submission. These too map to the creator/consumer tension modern media users must navigate.

The long-term goal is to develop a media practice that balances the wisdom of these four texts within themselves and between each other. It’s a humanistic knitting project that spans the species, and I think it’ll hopefully make me less frustrated with my own media experiences. Is such a Sudoku puzzle possible? I’m not sure yet, but if you follow along, you’ll know around the same time that I do.

Next I will move away from broad theory and textual basis and toward applying the “middling content” approach to navigating a particular political challenge: urban accessibility and immigration.

Huge thanks and appreciation to those of you that did listen and shared your thoughts though!

Every truth that has ever been discovered and shared has later been exploited by people who don’t even quite understand it. I am aware of this trend and trying not to perpetuate it myself.

Though technically only the 25th generation since S&H claim there was a skipped generation after the American Civil War. But let’s not overcomplicate this.

Importantly, the “knitting” that was the European Age of Exploration aligned with the “splitting” taking place in the New World already. Political tensions within the New World predated Western involvement; the insurgents that took down the Aztecs were primarily composed of their indigenous rivals the Tlaxcaltecs, with only 1-4% forces from Europe. (Which is not to excuse the horrors of colonialism, but more to show how the Strauss & Howe framework centers European ancestry at the expense of regional variations even within the Western regions it intends to represent.)

This is still excluding a growing number of Westerners who integrate aspects of the philosophy into their lives through its expanding application in talk therapy practices or self-help content like Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. It’s a big tent!

Varanasi’s globally significant religious tourism is independent of the Dhammacakkapavattana that took place a bit outside the city, which really speaks to both the breadth and depth of religious and philosophical traditions in India.

Which, despite my best efforts, I still certainly mispronounce.

This framework is from Majjhima Nikāya 44 (Cūḷavedalla Sutta), not the Dhammacakkapavattana itself.

One slightly confusing part of this is the use of “samadhi”; it’s the most varied in its translations, often as “meditation” or “immersion” (I like using “mediation” since my focus is on media.) Samadhi is also both the eighth step and the third grouping of steps, which is confusing to have samadhi be its own substep within itself. While I’m sure this violates the McKinsey style guide, this recursive property of samadhi is potentially intentional as a way to make the eight steps actually an infinite number of steps.

Named after the library named after the city named after the guy.

I spoke some about this in discussing how the Haymarket Affair trial was so well-suited to expand into a global holiday citing the Dao de Jing’s Chapter 11. The detail that “Chapter 11” connotes bankruptcy in American parlance but in the Dao De Jing reflects on the value in emptiness/absence is a fun coincidence.

If you heard the old Yogi Berra quote “When you come to a fork in the road, take it”, and you thought “I want this but an entire poetry anthology”, then the Dao de Jing is for you.

I long have held that anytime somebody tells me I should write, they are really just telling me I’m being too long-winded and confusing and I need to hash out my thoughts more clearly. But I think my grandfather was being genuine. Hopefully he’d think I’m doing the topics justice. Miss you and love you, Pepere.

There are apocryphal gospels about Jesus bringing clay birds to life and accidentally cursing fellow children to death that could be fertile territory for a GenAI slop sitcom.

To be specific, Nanda was a territory where Buddhism was growing among other Śramaṇa practices; it would evolve into Mauryan Empire led by the strongly pro-Buddhist Ashoka.

It’s worth noting that the commandment to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” is a part of the Hebrew prayer the “shema” and there is a great deal to read about it.

Interestingly, the Eastern traditions put action and practice first whereas the Western traditions put acceptance and belief first. This is why it can make sense to call a Western religion a “faith” but it often makes less sense to use that label with an Eastern tradition. At least in the texts I’ve highlighted here, the Eastern traditions emphasize aspiring to independent and empirical verifiability. Though practitioners themselves can obviously vary outside this highly simplified model.

Though I expect there is a point within 800 years of “occupying” a country where it just becomes “living there”?

Though I started this project before LLM-based chatbots were around at all, and prior to their use of “reasoning” and web search they were highly likely to confabulate quotes from the Dao De Jing in particular. It was interesting to see how asking about non-Western texts would be more likely to over-extend their ability to maintain accuracy. Similarly, you can’t trust the LLM’s interpretations of the text, and hopefully you can find ways to engage in conversations with real people. That is, after all, the point of the pocket canon!

...Everybody else compulsively tries to peel an orange in a single rind, right?

That said, I want to create a broad and cross-cultural framework, and so I will incorporate more academic findings from modern institutions going forward, potentially in a more conventional short-form newsletter format.