Law & Quoter: Trial by Geometry

A plea for quotation mark regulation; a journey into wordspace; ¿Cómo se dice “run”?

When walking last year near New York City’s Times Square1, typically a great joy of mine, I saw an ad that made me upset.

Obviously any reminder of ill-will toward a country I’m in is a bad vibe, but that wasn’t what upset me most. It was probably third on my list of concerns.

Primarily, I was upset because the ad was distorting a classic Maya Angelou aphorism. The quote is “when someone shows you who they are, believe them”2. While I never met Angelou, she seemed like the kind of person who would have considered “tells” as an alternative to “shows” when crafting an iconic line like that. The point of using “shows” is that you shouldn’t pay so much attention to what people say as what they do. People don’t know themselves well and are prone to lying; it’s their actions that give you insight into another person’s true identity. Altering the quote in this way3 completely confuses its meaning.

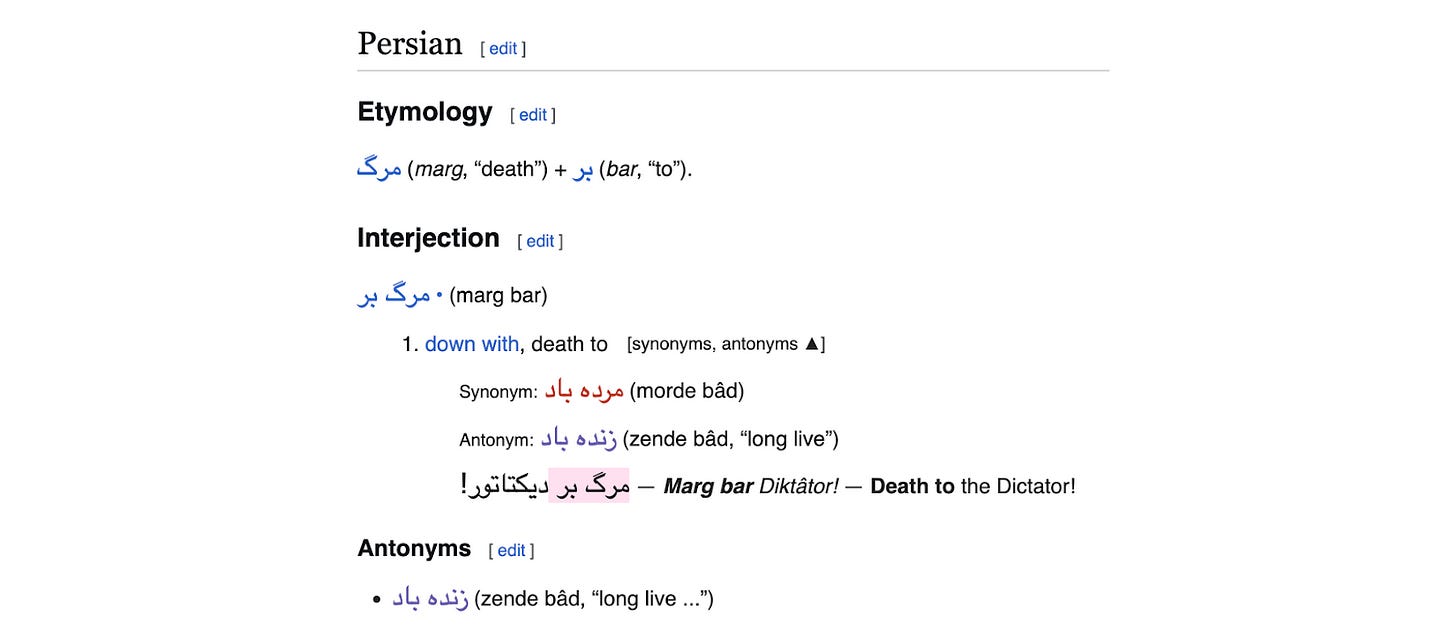

But then there was the thing I was upset about second-most: the use of quotation marks around words that I’m quite confident were not spoken. What was instead used was the Farsi phrase “Marg bar Âmrikâ” (مرگ بر آمریکا), which official Iranian sources tend to themselves translate as “down with America”. While Wiktionary lists “death” as the primary definition for the “marg” and “to” as the primary definition for “bar”, it also lists “down with” as a translation for “marg bar” earlier than “death to”.

Indeed, the same week of the Tehran University Conference they quote, CNN covered the Ayatollah’s qualification the meaning of the phrase: “it goes without saying that the slogan does not mean death to the American nation; this slogan means death to the U.S.’s policies, death to arrogance.”4 And even here, this is CNN’s translation5 introducing the literality of “death” into a more abstract and nuanced phrase. If a narrowly inflammatory translation is “death to America”, a more generous paraphrase could be “stop hurting us, America”.

This post isn’t going to discuss that particular quote in additional depth6, but it has a robust Wikipedia page with references you can read if you want to. As a non-Farsi speaker outside of Iran7, I can’t adjudicate what the word and phrase “really” means to those using it in Iran. I’m more concerned about how freely the media throws quotation marks around translated remarks.

The AP Style Guide asks that “Quotes from one language to another must be translated faithfully. If appropriate, we should note the language spoken.” The use of “faithfully” here fascinates me; if we must bring faith into this, I’d prefer “must be translated in good faith”, though that would be impossible to audit. Equally fascinating is the qualifier “if appropriate” before “we should note the language spoken”, which leaves much to discretion. The display ad that upset me appears to comply with the AP Style Guide, a noble achievement for an unmarked van.

There is a clear tension here between journalistic accuracy and audience comprehensibility. Quoting the actual words spoken would preserve nuance, but it would make the quote inscrutable to readers. How do we enable truthfulness in global media in a world where 82%8 of people don’t speak English?

In a recent encounter with dubious “quotations”, I experimented with new tech in an attempt to become a more sophisticated media consumer. For others who partake in media covering foreign-language-speaking speakers, this approach can be similarly useful.

¿Cómo se dice “run”?

The writer Gustav Flaubert is said to have written, “A good prose sentence should be like a good line of poetry—unchangeable… just as rhythmic, just as sonorous.” But he didn’t. (Technically.) What he did write was: “Une bonne phrase de prose doit être comme un bon vers, inchangeable, aussi rythmée, aussi sonore.” They mean largely the same thing, of course, but to change the words of a writer who insists his words are “inchangeable” seems almost mean-spirited.

This is not to criticize this translation, though. My French is somewhere between my Farsi (nonexistent) and my Spanish (bad), but I can still grasp much of the original, and the translation seems pretty solid. It’s clear that the English rendition took effort to preserve both the sound and sense as best as possible. And yet… we can observe compromises resulting from unresolvable tradeoffs in the act of translation.

Let’s note a few of them.

While “bon vers”9 has two syllables, there are six syllables of “good line of poetry”; the tightness of the phrase in French lets Flaubert accelerate up to the ellipsis, a build of excitement and then space that is to my ear more musical and exciting. Preserving clarity here means sacrificing the “Flaubertian rythmée” of the line.

To maintain the sort-of octuple-quaver feel of “aussi rythmée, aussi sonore”, the translator uses “just as rhythmic, just as sonorous”. But “just as” is enclosed in consonants, and it doesn’t sing free like “aussi” does. It’s supposed to be musical! To substitute “also” is better from a pure-sound perspective, but fails to focus the meaning. Again: a trade-off!

Translating “sonore” to “sonorous” seems as rote as one can get. Yet the English word “sonorous” is just so much less sonorous10 than the French “sonore”? It sounds too much like the negatively connoted “onerous”11 perhaps? The translator has chosen the seemingly obvious equivalent and yet fails to capture the essential aesthetic.

It is for this reason that I skipped reading some of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in 12th-grade English12. Flaubert tormented over a precise and particular articulation of his concepts -- only for me to read completely different words? Absurd.

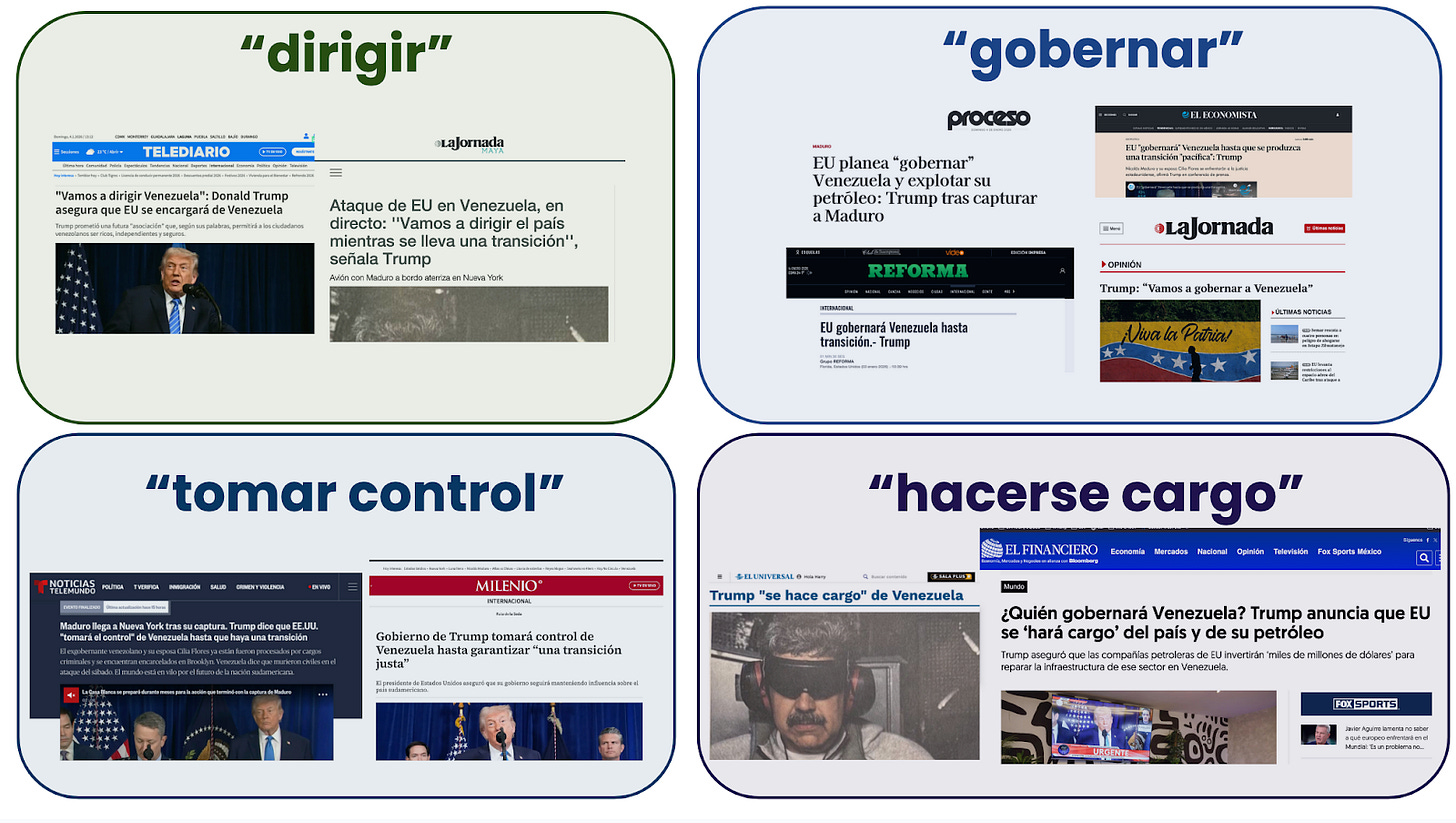

I get the sense that Donald Trump does not suffer so long to find a precise Flaubertian “rythmée” in his phrasing, but it’s a quote of his that has brought me back into translation turmoil. I’m spending January in Mexico City, and to prepare for a presentation I’ll be giving in Spanish in March, I’ve been reading headlines in national papers. And I was intrigued by the varied translations provided of a quote Trump gave in his press conference on the American intervention in Venezuela: “We are going to run the country.”

To give some credit, there is some strategic ambiguity in the monosyllabic, quasi-colloquial “run”. In English, this could cover a wide range of scenarios, broadened further by Trump’s particularly loose use of language. And the breadth of the term makes interesting work for translators -- does one try to find a similarly broad term? or does one read into the broader context to infer specificity?

Ultimately, different papers put different words in the same mouth.

While my Spanish is B1-level13 at best, these are all at least partial cognates14: “dirigir” for “to direct”, “gobernar” for “to govern”, “tomar control” for “to take control” and “hacerse cargo” for “to take charge”. They are all also seemingly more specific than “run”; although “correr” is used in some Spanish-speaking contexts to mean running a computer program, it is not idiomatic Spanish to use it for running an organization or a country.

There is also inconsistency in deciding between Spanish’s two distinct future tenses: near future and simple future. This distinction does not exist in English, but it has some implications as to the certainty and timeframe for future action. To use the near future (“futuro próximo”) tense suggests a resolved decidedness and short-term action, whereas the simple future (“futuro simple”) suggests a more general prediction or anticipation.

With the variance in possibilities in choices, I was curious if there was some way to evaluate the quality of each choice. Since we’re in a golden age of linguistic computational capabilities, I wrote a short script to assess “semantic similarity” between each translation and the original quote.

Adventures in Wordspace

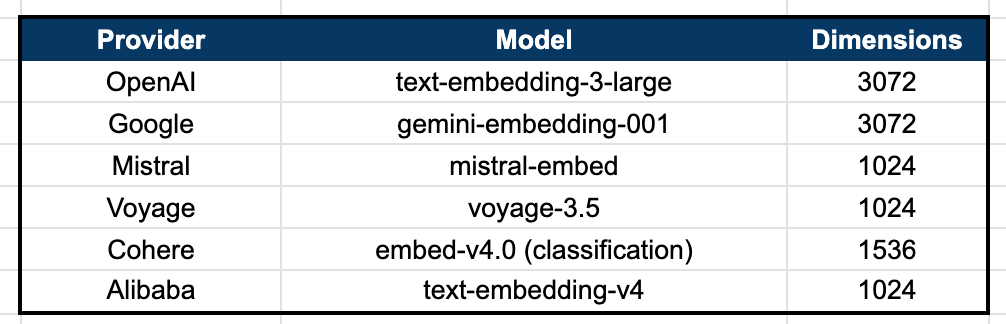

The term “translation” is not just used with words, but also with geometry. To translate a shape, you just move it consistently in a single direction. And in the world of “Large Language Models”, geometrical and linguistic translations are broadly similar15 operations. Many who use ChatGPT16 may be less familiar with some of the underlying technologies, underneath the chatbot is an “embeddings” model like OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-large that can place any word or sentence within a 3072-dimensional space17. Many of the major AI providers make these embeddings models available to developers.

I’ve used these models in the past for activities like sentiment analysis or topic clustering, because similar words will be closer to each other. Positively associated words have a sort of hyper-geometrical neighborhood, as do words in certain categories: adjectives, words in Laotian, technocratic jargon, spooky noises, etc. I think of LLMs as a sort of “hyper-dictionary”, where instead of just providing a set of words that are “equivalent”, you can identify the proximity of every word to every other word.

With this theory guiding me, I used six different models to evaluate the “proximity” of our source content. I started by selecting the three that I hear the most about people in professional conversation: OpenAI, Gemini and Claude. From there, I added three that I thought might represent “outside voices” in my sampling mix: Mistral (for a French model), Ali Baba’s Qwen (for a Chinese model) and xAI (for a MAGA Republican model). Alas, since Claude and xAI do not make their embedding models public18 at the time of this analysis, I substituted in the embedding models they refer to in their developer documentation: Voyage and Cohere respectively.

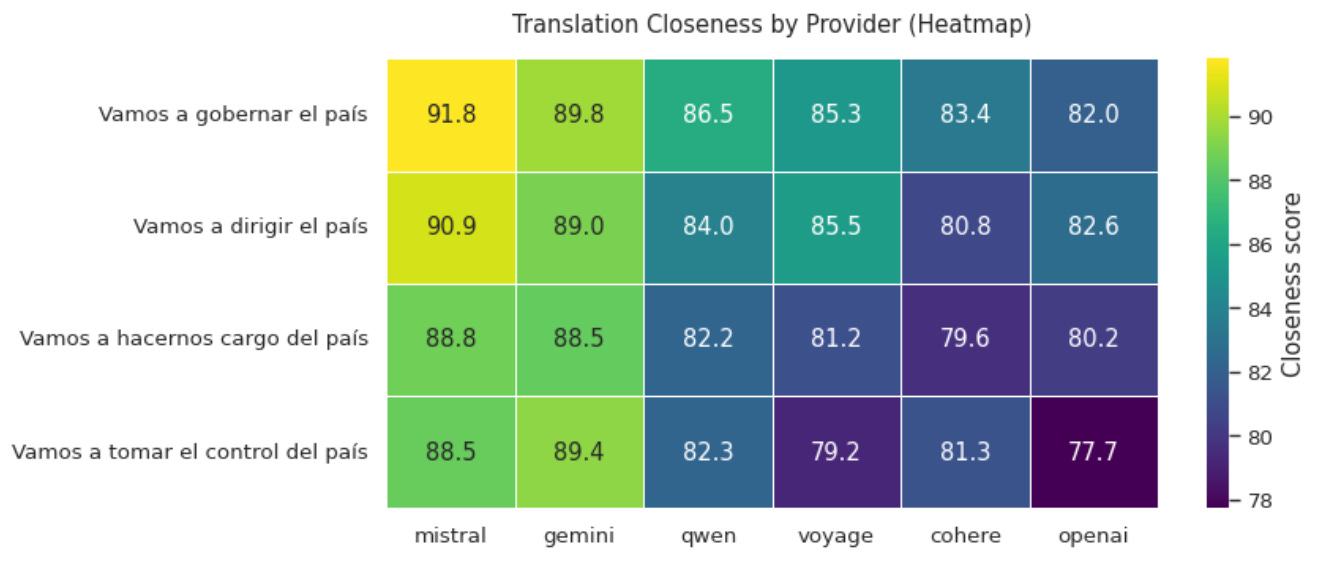

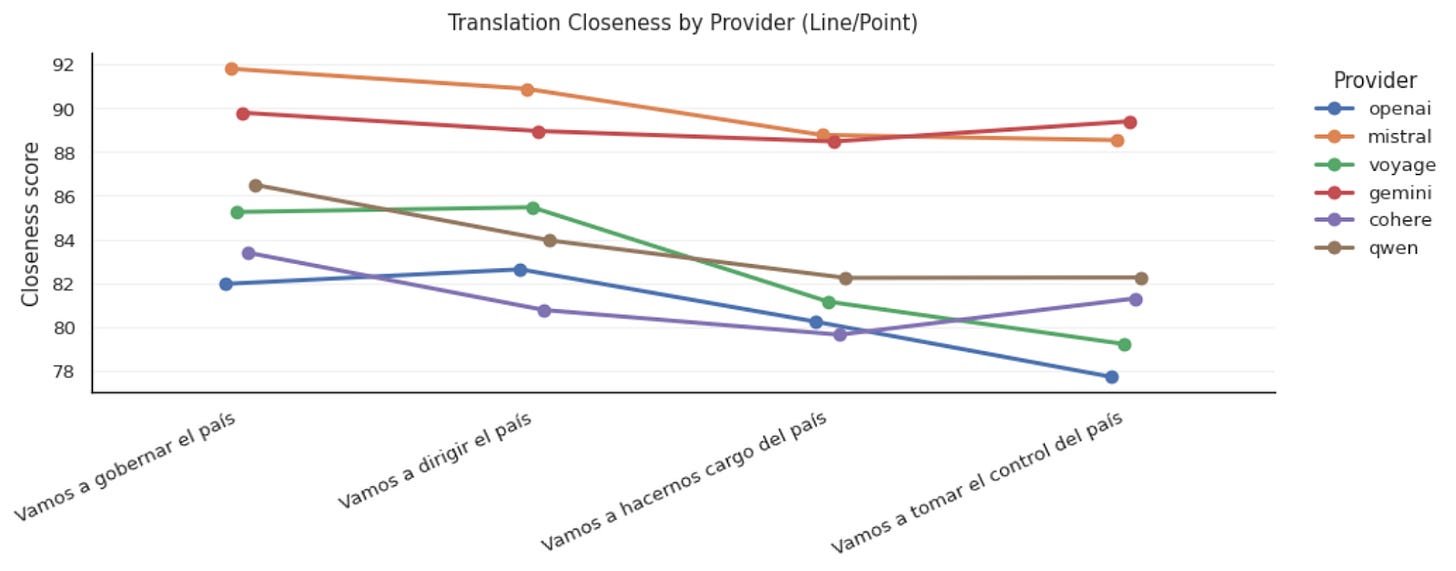

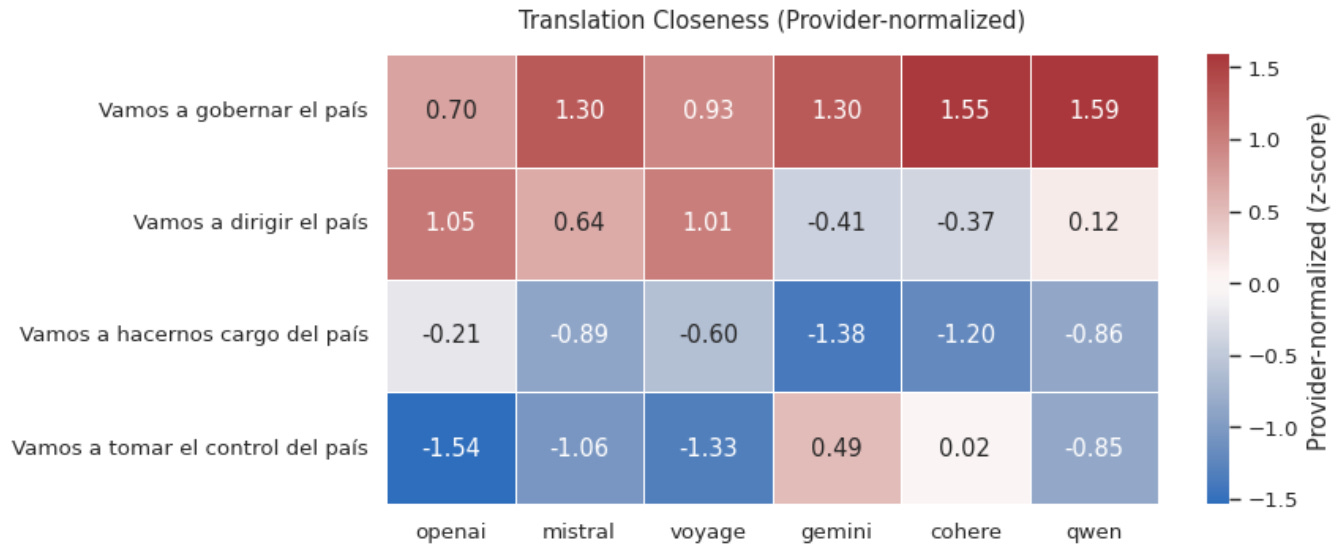

Using this mix of embedding models, I can evaluate and compare how “close” in “semantic space” the terms are to the original quote: “We are going to run the country”. (I list caveats for this at the end of the analysis; there certainly are a few.) Ultimately, we find that though the models provide different scores, they tend to agree on translation preference.

From left to right, we see that Mistral and Gemini are more likely to find all the quotes as similar, with Cohere and OpenAI seeing them as less similar. And from top to bottom, we see that the “closest semantic match” in terms of average cosine similarity is “Vamos a gobernar el país”, which indeed was the most common translation I came across. This seems to agree with the decision of many publications to choose that wording within their translation. (Three of the eight I came across that used quotation marks.)

It is notable, though, that there’s some disagreement between models. The overall second-place choice “dirigir” is the top choice of OpenAI and Claude’s recommended Voyage, and both Gemini and xAI’s recommended Cohere had the lowest overall performer “tomar el control” as their second-choices.

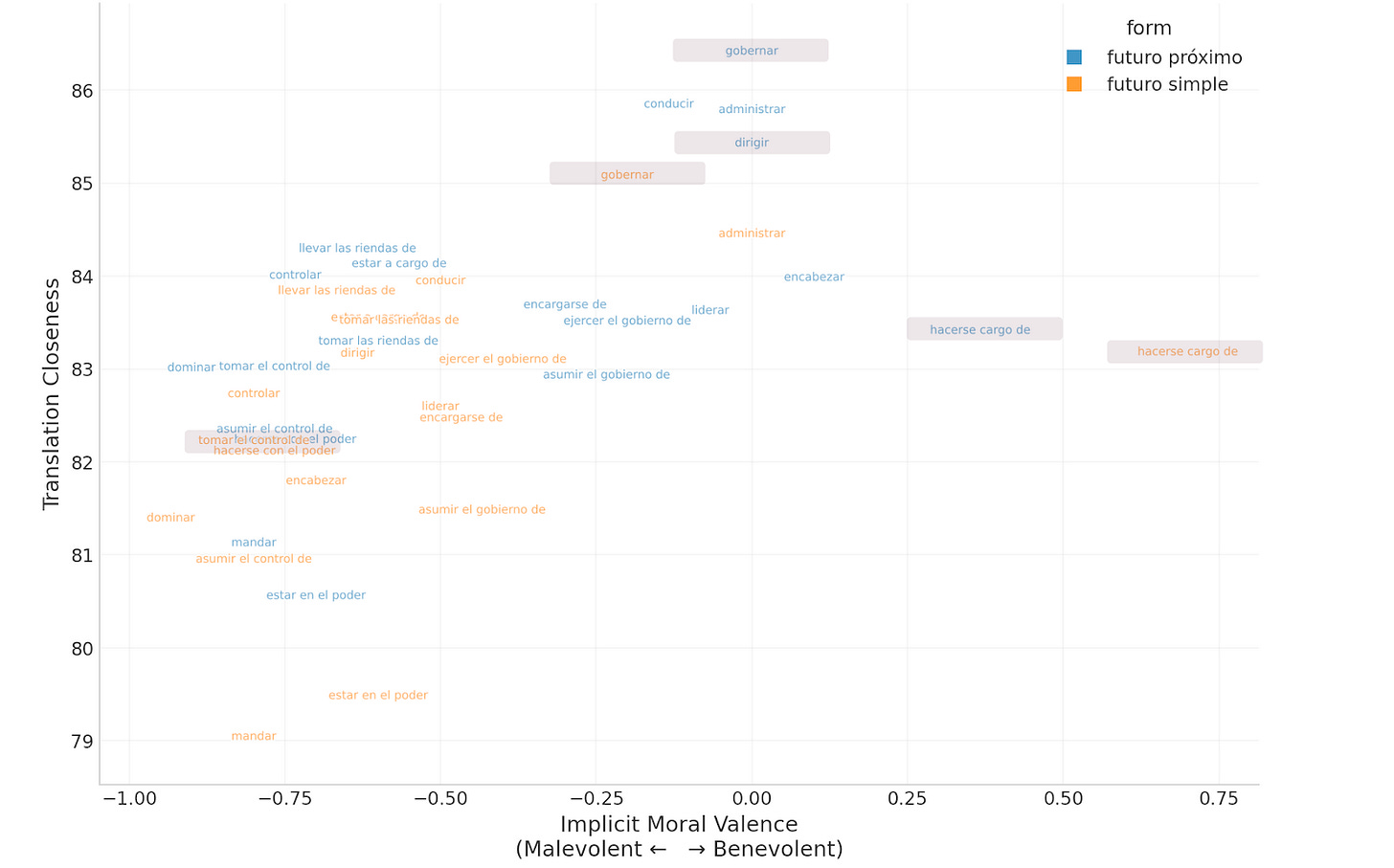

But these four verbs are just a small subset of the possible translations a headline-writer could use. We want to know how these compare to the broader range of possibilities. I generated a set of 20 different verbs, and for each I created a quote in both “futuro próximo” (near future) tense and “futuro simple” (simple future) tense, resulting in 40 different quotes to evaluate.

As an additional dimension, I used gpt-4.1-mini to classify19 each statement from between -1 and 1, with -1 coded as “malevolente / coercitiva / dominadora / amenazante” (malevolent / coercive / dominating / threatening) and 1 coded as “benevolente / orientada al servicio / inclusiva / cariñosa” (benevolent / service-oriented / inclusive / caring). This gives a sense for which translations may be more politically loaded than others.

We find that the four verbs used in headlines occupy somewhat distinct areas on the map of wordspace we’ve generated.

The verb “gobernar” was not just the best fit of the actively used examples but the best fit overall, particularly when expressed in near-future tense. It was also deemed largely neutral in tone.

The verb “dirigir” was also a top verb among the full range of options, though “conducir” and “administrar” performed better than it. I only found an example of it being used in near-future tense, but interestingly it was considered malevolent in simple future tense.

The phrase “hacerse cargo de” was the most positively associated term of all that we tested in both tenses.

In contrast, the phrase “tomar el control de” was deemed among the most malevolent potential translations. Among the highly negative translations (such as “mandar”20, “dominar” and “controlar”), it was among the top for semantic closeness.

In general, we also found that the near-future tense tended to be deemed semantically closer in meaning than the simple future tense, and the use of simple future often increases the degree of valence -- that is, negative verbs become more negative and positive verbs become more positive.

There could be some utility in approaches like this when evaluating media bias in translations, with value for consumers reading the news or for public figures who are covered in the news. There are a few limitations important to consider.

It’s not public what the content was used to train these LLMs. The headlines I was looking at were primarily Mexican headlines, but there are regional variations in the language, and it’s unclear how much of an LLM’s source material is from Mexico vs Spain vs Argentina vs elsewhere.

This is a translation process that is naive of any meaningful context of the quote. It does not know that the quote is being said by Donald Trump, and lacks insight into his particular style of using words. It does not know that the countries involved are the US and Venezuela, and the history of relations between said countries. It does not know the tone of voice in which the quote is stated. Professional human translators are likely incorporating these factors when translating, and I expect it is these factors that result in different publications making different choices.

There are different approaches to semantic distance and “cosine similarity” is just one of them. I’m not 100% confident that this is the best way to examine gradient-synonymousness in this way. If there’s interest in this topic I could explore this further.

I’m reminded of that e. e. cummings poem that basically says not to try to analytically approach humanistic subjects in this kind of computational way. I think of that poem a lot because I tend to approach these subjects in this way a lot. So maybe this isn’t a useful direction to take things at all.

With limitations acknowledged, you are welcome to play around with this approach21. I do generally prefer to analyze these sorts of questions with embedding models because you can plug in the same inputs and receive a more consistent22 output -- rather than the randomization or personalization found in the web applications. Transparency23!

And speaking of transparency, I have a few recommendations based on this brief exploration.

Distrust in Translation

The point of all this is to say that translations involve judgment, and you may or may not agree with the judgments translators make. But while I’m calling attention to this issue, I don’t want this to drive people away from consuming shared media. Quite the opposite! The Middling Content mission is to support the development of “middling content” -- that is, content that mediates the human experience, forming common experiences that enable connections across lines of difference. So in an attempt at being constructive, here are some recommendations.

For Writers:

If the Associated Press wanted to improve their trustworthiness, I’d recommend a revision to their style guide that requires some manner of notating when a quote is translated. Ideally, not only the source of the quote is named but also the translator, since all translations inherently have bias. A translation is just an inter-linguistic synonym for a foreign-language quote, and one would never put a synonym within an English-language quote without notating or explaining.

Even though I trust expert translators, most other expert judgments (research papers, presentations, statistical estimates) transparently name the experts involved so one can investigate their affiliations and credentials.

For Readers:

My guidance here is just to always be particularly careful with how translation is presented to you. If a non-English speaker is being quoted in English saying something that influences your opinions on key political questions, it’s likely worth investigating the source material. As the US seems to be engaging militarily outside the Anglosphere, this will be increasingly important to avoid manipulation.

There don’t seem to be rules when quoting a translation -- different publications can reach different decisions, and ultimately they are all stretching the truth since words and phrases are essentially never truly equivalent.

Sometimes you’ll find that the quote reflects the original statement, but sometimes a quote is just a “quote”.

Technically it was Bryant Park, but I consider anywhere three blocks from Times Square to be Greater Times Square. Home of the beating heartbeat of the universe and debatably the only wonder of the modern world.

Technically she also said “the first time” at the end of it, but omitting that is less grave than altering a key verb.

Indeed, this sequence of words was particularly triggering because a woman once used this same verb-swap while dumping me. It is the only other time I’ve heard the saying construed this way. And for the universe to remind me of that moment while I was trying to enjoy “the world’s plaza” Times Square -- honestly pretty rude.

He could be lying about how he personally uses the phrase. He was not popularly elected to speak definitively on Farsi semantics. Indeed, he was not popularly elected at all.

Though it is not clarified, I assume this is a translation since the quote was from an interview on Iranian television.

With such a common phrase, I would not be surprised if some say it with hate in their hearts wishing the destruction of the United States; it similarly is reasonable that some say it to merely voice criticism of an international order that hurts their interests. Though I lack direct awareness, I do believe people have legitimate grievances with the Iranian government; the existence of this quotation is not a smoking gun signifying hostile intent.

I’m aware that much of the Iranian diaspora population is highly critical of their government, but I’m also aware that diaspora populations are highly critical of their governments in general -- thus their relocation. Having spent much time as a “digital nomad”, I’m aware that the American diaspora community is highly critical of the US establishment, more opposed to vaccines, etc.

Ethnologue is the leading source for these kinds of statistics, but as with everything else there are complexities-upon-complexities. What counts as a language? How many words count as speaking? Do reading/writing/listening competencies matter?

Perhaps saying “verse” instead of “line of poetry” is comprehensible with a footnote to clarify that it’s meant for poetry specifically. Aren’t footnotes great?

I’m reminded of informing my French-Canadian grandfather that his surname “Vadeboncoeur” shared some etymology with the British surname “Bunker” (“bon” + “coeur”) and him having a distaste for the sound of the anglicized cousin. I use 帮课 (“bāng kè”) as my Chinese given name, which perhaps he’d like even less; it means “to help with text”, kind of like I’m doing right now!

Though “onerous” comes from old French, there doesn’t seem to be a modern French counterpart.

Apologies to my 12th grade English Literature teacher who is a subscriber! I was a terrible student but I loved that class.

One of the most annoying things about using ChatGPT for language practice is it insists on providing constant sycophantic assurance that my competency is at a C1 level when it is very obviously not. Large Language Models, built upon massive repositories of text, are quite good at identifying when language is being used unusually, which is helpful in the learning process.

A “cognate” is a word in a different language with shared etymological roots.

While some aspects of language can reveal themselves as pure translation operations within datasets, this is not the case with contemporary embeddings models as far as I understand it. There have been studies that find generalizable transformations across separate monolingual embedding spaces like this 2013 paper from Mikolov, Le and Sutskever -- yes, that Sutskever. A recent 2025 paper from Kim and Lee did find the presence of a “language vector” when examining the relative positions of translated text in embeddings, but it isn’t a stable reversible process.

The particular operations of user-facing sites like ChatGPT is opaque though, and it is possible that publicly available embedding models are not meaningfully involved.

If the model is normalized, as many are, all embeddings will exist on the surface area of a many-dimensional hypersphere. It’s not possible to visualize, but still kind of neat to know there’s a sort of shape to these models.

This is in itself interesting, as it does limit ways the developers could investigate potential issues within the core LLM, which is unsurprising for xAI which has locked down developer access to its platform, but was more surprising for Claude.

I used the average score of seeds 0, 1 and 42 with the OpenAI API for replicability, though their documentation does not guarantee consistency over time.

AMLO used “mandar” in his message to Trump on X: “Por ahora no le mando un abrazo.” Essentially, he tells Trump that for now he won’t send a hug -- “abrazos no balazos” (“hugs not bullets”) was a major campaign slogan for AMLO, and I like to follow the discourse about its effects. Though “mandar” has a meaning closer to “send” in his sentence, it can also mean “to run” sharing negative overtones with the English-language words “command” and “mandate”. To me, the warm tone of “abrazo” (hug/embrace) contrasts with the colder authoritarian “mandar” (send/order/direct), though I’m not sure if that connotation conflict exists in Spanish.

If a few people say they’d be interested in an online tool that could run this analysis for them, I could put one together pretty quickly. I just would want to make sure this is something other people care about.

It’s possible that these models do change from time to time though, so if you’re reading this long after initial publication my metrics may not be replicable.

If you subscribe and message me, I’ll even share my colab notebook to reproduce the graphs!