Health Policy in Saw VI & Sharia Law

Concept testing global models for a more humane death panel.

You can tell a lot about someone’s politics from their favorite film in the Saw franchise.

For a series that found its start in the violence-glorifying post-9/11 milieu alongside torture tales from 24 to Hostel, the Saw series has sustained itself long enough to see itself shapeshift politically. Spiral: From the Book of Saw was a post-2020 resistance-inflected critique of police power, and other installments take on the legal system (Saw III), medical scams (Saw X) and predatory mortgage lending (Saw VI). And then there’s the feel-good Saw V, which is a sort of allegory promoting teamwork and collaboration -- almost sickeningly sweet for a series that is normally just, well, sickening.

The scattershot worldview of Saw universe is a major critique of the series1, and it is indeed very disorienting. But it also allows the films to serve as a kind of social barometer measuring shifts in attitudes about political violence over the two decades it spans. Specifically, you can plot how the stories and cases modulate in two key ways: the depicted efficacy of violence and the status of the violence’s victims.

And indeed, because this blog aims to help people be more mindful of the messaging in media and because putting films in biplots is an established interest of mine, that is exactly what I’ve done.

The broad arc can be observed while avoiding the (literally) gory details, as I try to keep this a family newsletter/blog. Perhaps another newsletter can dig deep into the particulars of Saw’s journey from a political climate of fascistic violence to one of anarchic violence. For now, I will just paint in broad strokes and group the films into four phases.

Phase I: Post-9/11 Violence Fantasy

Saw & Saw II (2004-2005)

Victims are primarily low-level criminals. The main victim in the first Saw is a doctor, but the other victims are lower status: targeted for lying, using drugs and practicing self-harm. Saw II targets petty criminals (a drug dealer, a prostitute, a fraud) and also innocent folks improperly jailed.

Traps are therapeutic in intention. The systems are designed by Jigsaw to help “save” people. While many die in horrible deaths, Amanda and Dr. Gordon escape, and Amanda articulates gratitude.

Historical Context: This peculiar concept of “therapeutic violence”, imagined as a sort of constructive abuse endured by the recipient, is perhaps somewhat fitting for a time period when the US held foreign policy goals of nation-building through military action. There was a belief that violence against a population, if engineered appropriately, could serve a noble purpose.

Phase II: Disillusionment with Violence

Saw III & IV (2006-2007)

Victims are still relatively low status. Saw III targets Jeff, a father who is vengeful about his son’s death; Saw IV targets Riggs, a police officer who tries to save everyone around him. Other traps target a drug addict, a defense lawyer, a couple in an abusive relationship, a drunk driver and a lenient judge.

Traps are ineffective and occasionally rigged. Despite a seemingly cathartic experience, Jeff is unable to control his rage, resulting in various deaths of loved ones. Similarly, Riggs cannot stop himself from trying to save people, ironically resulting in various deaths of loved ones. It’s a dark turn from the more optimistic view of Phase I, plus there are new “false hope traps” set up by Jigsaw’s apprentice.

Historical Context: By 2006, a majority of Americans would see the Invasion of Iraq as a mistake, with polls showing two-thirds of Americans opposing the war.2 This parallels the shift in the treatment of violence as a constructive and supportive force.

Phase III: #Occupy Era Elite Purification

Saws V, VI & 3D (2008-2010)

Victims are increasingly powerful. Saw V targets five people tied to the real estate company cover-up of an arson that killed 8 people; Saw VI focuses on a health insurance executive; Saw 3D focuses on a celebrity charlatan. Other traps focus on the rivalries between Jigsaw’s apprentices.

The traps are generally fair and well-intentioned. Victims in Saw V & VI appear to have conversion experiences, though Saw 3D reverts toward hopelessness.

Historical Context: This turn against high status professionals takes place in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Obama-era optimism drives a belief that interventions can be redemptive and reforming.

Phase IV: Increasingly Anarchic Anti-Elitism

Jigsaw, Spiral & Saw X (2017-2023)

Victims mostly remain higher status. Spiral focuses on police corruption; Saw X covers wealthy clinic scammers.

The traps are ineffective and often rigged and spiteful. We do not see growth from the key victims within each film.

Historical Context: Populism and anti-elite sentiment contribute to the election of Donald Trump and the #MeToo movement. Trust in institutions in the US is degraded to previously unforeseen levels in measured records.

So we see that this decalog of films traverses the entire political compass; attitudes on economic redistribution are a proxy for the perceptions of redeemability, and attitudes about authoritarianism show whether one prefers violence to constrain the powerful or to keep the masses in alignment. Which suggests that we’ve moved from a political climate of fascistic3 violence to one of anarchic violence.

In today’s newsletter, I want to focus on the two films that take, as their victims, elites within the healthcare system.

Competing Treatises on Healthcare

Topics of medicine are commonplace in the Saw franchise as the protagonist’s central motivation is supposedly his purpose-clarifying encounter with cancer treatment. So it’s unsurprising that the tenth and most recent film focused on this particular bogeyman, but what was more interesting was how the approach was framed differently from Saw VI, which also took on healthcare.

The films have been on my mind since around December 4th of last year, for reasons that will probably be clear after discussing the plots and villains in greater detail.

Saw X main victim Cecilia Pederson operates a fraudulent healthcare clinic and scams desperate patients into paying for sham therapies. She and her employees scam John Kramer AKA serial killer Jigsaw, and he takes retribution on them. She tries to break traps with little regard for the rest of her team, but Jigsaw has thought steps ahead of her and ultimately she is abandoned to die. There is no learning and no character growth, it is simply a violent revenge fantasy on a cruel elite.

This is in somewhat contrast to the more wonkish and specific Saw VI, where the main victim is William Easton, an insurance executive, who completes a series of traps including choosing which of his employees live and die. Despite the cruelty, there is an Obama-era optimism to Easton’s arc, and he reaches the end seemingly having learned the evil of his ways. But alas, his final challenge is to convince the widow and son of a man to whom he denied coverage to spare his life; he fails.

Whereas Cecilia’s scheming villainy is run of the mill, William is a product of a system and seems to be capable of change. He is doomed only by the fact that his conversion came too late. Violence tragically begets violence.

Saw VI and the killing of William Easton also sparked mixed reviews. With a Rotten Tomatoes score of 39%, it’s actually the third highest rated film in the Saw franchise. Here’s a taste of what critics had to say:

“Instead of being punished because they take their lives for granted, which had a certain classicism to it, they’re now punished for being mortgage lenders or health-insurance adjusters.”

“I wasn’t all that curious to see the explosives cuffed to [the insurance executive’s] hands and feet detonate if he failed these tests. Yet suddenly the carnage has a wicked bit of literal and metaphorical social resonance.”

“Most Americans, however, would probably prefer to pay lower premiums than witness their HMO manager being dissolved from the inside out by hydrofluoric acid.”

James Franklin, “'Saw' horror films aren't cutting-edge thrillers”, Oct 30, 2009, The Philadelphia Inquirer

It’s probably to be expected that The New York Times, ever the mouthpiece of the pro-institutional left, would pine for the “classicism” of the old days when it was the downtrodden who were “punished”. In contrast, The Boston Globe at least recognizes the compellingness of this revenge fantasy, perhaps befitting its history opposing the Vietnam War and exposing sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. Meanwhile The Philadelphia Inquirer, matter-of-factly, is just trying to keep us solution-oriented.

These themes sound familiar. In the media after the UnitedHealthcare CEO assassination, the mainstream coverage hit similar notes to these Saw VI reviews -- either dismissing the angst outright or dispassionately acknowledging that the system frustrates many. Many, though, expressed surprise that so many people would celebrate a killing of this kind. I expect none of those people watched Saw VI. Such violence was precisely the cathartic climax. And while the film was no box office smash, it played on 4000 screens, was profitable and had an opening weekend gross over 3X that of Babygirl.4

I do wonder if anyone who watched Saw VI was swayed by it in any meaningful way -- in how they voted or what career they pursued. I’m surprised I was able to watch all the films in the series; none of the Saw movies are really watchable anymore. I watched the first several with my brother when we were teenagers, often in theaters, as a kind of Halloween tradition. When I attempted to watch Saw X in 2023, I spent about half the runtime staring at the floor of the Logan Theater. (It’s a fine floor and certainly preferable to watching human dismemberment.)

Going to watch a horror movie in a movie theater used to be a sort of group exposure therapy for me, confronting themes of death alongside my fellow mortals. When people I love started dying, the art form became much less therapeutic. But hopefully I’ve seen enough horror films in my youth to guide my moral compass appropriately, and maintain my focus on constructive work.

My work, of course, is research. And with so much conversation about healthcare in December, I wanted to more deeply understand sentiment, and so I ran a couple surveys, and I’ll close out today’s newsletter with a few findings and notes, to hopefully help everyone feel a bit more aware of healthcare attitudes.

In 2023, as a part of a sabbatical project, I built my own survey platform, and it’s my goal now -- about 18 months later -- to regularly share stats and insights from that platform. Mostly I’ll share media-related perceptions, as they relate to my other writing and projects, but in this case I wanted to investigate the healthcare question in particular.

And ultimately, I found that a sizable minority of Americans are displeased with their access to healthcare.

Overall, though, it is worth noting that Americans still outperformed international measures of healthcare satisfaction. The effects were slight, and of course it’s important to recognize that the US is spending much more on their healthcare than the international comparison group. Still, it is misleading to construe that Americans dislike their healthcare. Over 3 in 4 are to some degree satisfied!

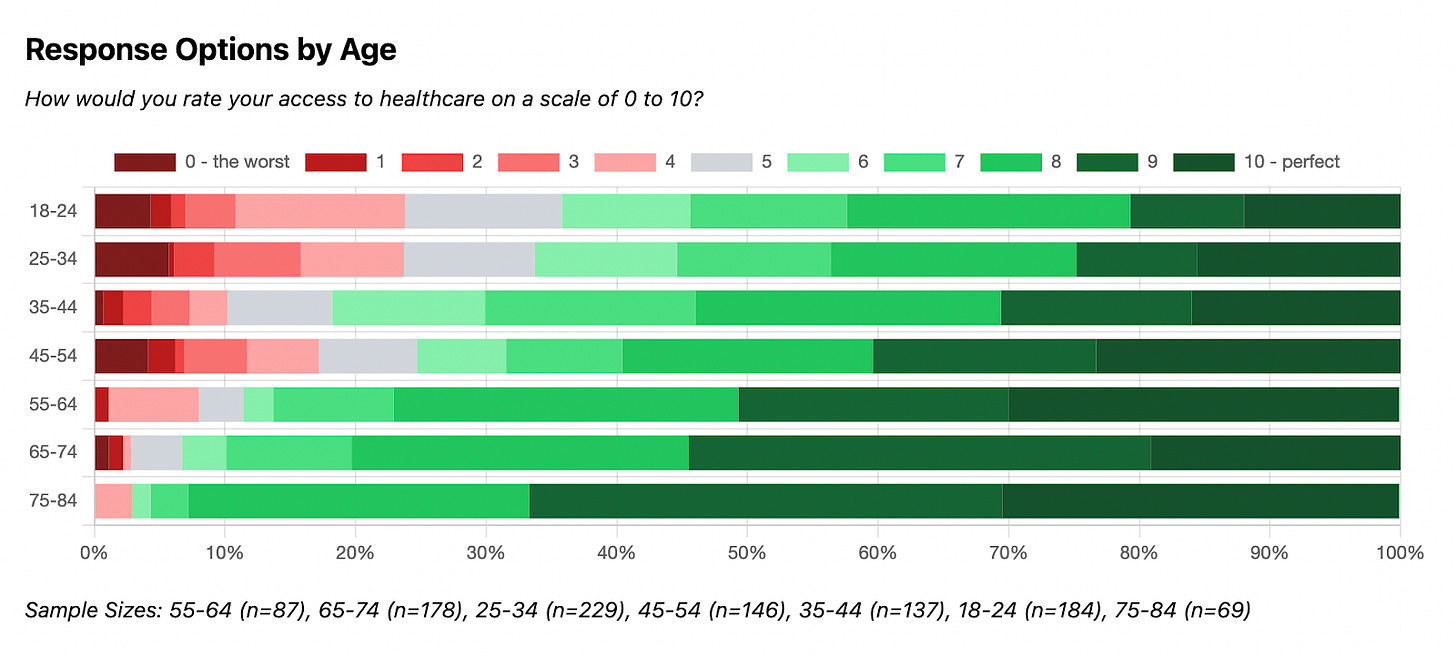

That said, there are substantial divides in satisfaction across demographic groups. You’re largely on your own until you make it to Medicare age, but many Americans don’t make it to 65. So discontent is most pronounced among younger demos like 18-24 and 25-34.

Satisfaction with the current system is just one metric though. A system that occasionally condemns people to death can only be so popular. But I did want to investigate options to see if perhaps there might be a more popular option out there.

Concept Testing a Global Historical Model of Health Insurance

My main curiosity was sparked by my brief exposure to Islamic finance concepts, where I was familiar with a more community-oriented program called “takaful” that is specifically designed to avoid exploitation (“riba”) and excessive risk (“gharar”). Being conscious that people may generally reject foreign words, I used an LLM to generate a neutral but descriptive overview of both these American and Islamic concepts of insurance.

Market-Driven Insurance: A primarily for-profit healthcare model where individuals or employers purchase insurance plans, with access and cost determined by market competition and profitability.

Cooperative-Driven Insurance: A non-profit healthcare model where members contribute to a shared fund to cover costs for those in need, prioritizing collective welfare and returning profits to members.

This framing is quite broad, and allows people’s own anxieties about for-profit and collectivist systems to drive their preferences. And ultimately, we find that Americans overall seemed to tilt toward the takaful / cooperative system rather than the private / marketplace approach.

Further, Americans seemed more supportive of the cooperative approach than those in other countries, which to me has a whiff of a “grass is greener” effect. But in the US and abroad, the tilt is toward takaful, the sharia-compliant cooperative-driven approach to health insurance.

Also, there is substantial variance within the US population by age. Over 80% of those 18-25 lean toward the cooperative approach, whereas the split is closer to 33%/67% for those that are Medicare age. Still, in all age groups there is a preference for the cooperative approach when presented in abstract.

I initially thought of just titling this newsletter “4 in 5 Gen Zs support Sharia Law”, but a friend of mine told me that would probably make people unsubscribe. But if you want to share this newsletter with someone and tell them “look, Gen Z supports Sharia Law” to get some buzz and direct them to my newsletter, then I’m okay with that.

The Teenage Civilization

In connecting to the themes here at Middling Content, I want to return to topics of media and make a couple points.

We are occasionally told our times are unprecedented by people who haven’t investigated the full scope of human history.

If we approach global concepts in good faith, we can often find there is something for us to draw on.

Healthcare is indeed a thorny policy challenge. The stakes are life and death. That said, the challenge is not at all a new one. Western countries have only participated at scale in global commerce for a few hundred years, whereas Islamic finance has supported transnational merchant classes for over a millennia.

Most people are familiar with the concepts of “Millennials” and “Boomers”, but not many folks aren’t as familiar with the theory that underlies the terms. Strauss & Howe identified a four-phase cycle that they trace back to the “Arthurian Generation”, which covers people born between 1433 and 1460. This makes Gen Z the 26th generation, which is why they are named for the 26th letter. But I don’t quite agree that 1433 is the right place to start, and I’d instead propose starting with the Glorious Generation of those born between 1649 and 1675. The Glorious Generation are a Hero Generation (like those that fought in the American Revolution, the Civil War and WWII), and they’re best known for establishing the first enduring constitution-centered system in the anglosphere, with checks on royal power. In that way, the Glorious Generation is the first generation that had agency over their own destinies, co-creating a textually defined system of governance rather than merely being subjects of a single individual ruler.

If we start with the Glorious Generation, then Millennials are only the 17th generation actively participating in this Western text-centered system, with Gen Z the 18th5 and Gen Alpha the 19th. In this way, I think of the West as “the teenage civilization”, which highlights some of its strengths like dynamism and idealism.

Each Textual Tradition Has Its Own Glorious Generation

With the recent regime change in Syria, I was occasionally hearing vague and speculative concerns expressed about “Sharia law” in the news, which would be accompanied by individual examples of violence or abuse. The development of Sharia law (or just Sharia, which roughly translates to “way” or “law”) was the Islamic shift in governance approach from person-centered to text-centered.6 It’s broad in the topics it covers, including mundane like healthcare that may in fact have broad appeal. To draw an analogy, the Islamosphere’s “Glorious Generation” would have lived in the 11th Century, putting them near their 50th generation.

Since this shift, centuries of managing large global market-based systems drove legal thinking around regulating risk (ghirar) and exploitation (riba). The age of a text tradition is the only relevant factor to consider when comparing them -- text-based traditions in China and South Asia are even older than Sharia -- but age does connote a certain resilience and sustainability. My hope is that it makes you less likely to dismiss the entirety of a text-based tradition until you’ve investigated it in good faith. Oftentimes if the most powerful rhetorical attack against a person or group is to use a vague, foreign-sounding word, that may be a sign that there is no real basis for concern.

A final thought: In geometry, many of us probably learned of Pascal’s Triangle, but we may not have learned that it is in some places known as Khayyam's Triangle since Persian mathematician Omar Khayyam had published it over half a millennium earlier.7 Sometimes I worry that we may be similarly handling the design of pro-human market-based systems, trying to invent a thing that already exists. If a better world is something we are truly invested in seeking, we should study the most time-tested versions of these systems; we shouldn’t burden ourselves with an obligation to reinvent solutions.

Send Me Your Questions!

If you are reading the news and wonder “what do people think about this topic?”, then email me / DM me and I can run a survey. Maybe you already have a question. Maybe you want me to re-ask a question I reported on today in a way that would be a bit more fair/clear. If so, let me know! Happy to do so.

Hopefully after analyzing the messaging within the Saw films, you are able to see how media analysis helps us understand shifts in political attitudes, and how the fantasies we feature on screen make their way into the real world. Which hopefully in turn makes you think about the creators you support and the media you sustain yourself with.

And further, I hope I’ve communicated the value of broadening our aperture when we look out into the world, incorporating both direct feedback in the form of surveys and perspectives outside our most familiar geographies and eras. There’s a lot out there.

Middling Content helps readers take ownership of their media diet to stay centered and sane. Subscribe for our weekly newsletters, where we bring data and theory together to provide tools and frameworks to help you take back control of your eyes and ears so you can achieve your best life.

Along with incomprehensible interweaving of narratives, constant retconning and, of course, the unwatchable violence.

“Poll: Approval for Iraq handling drops to new low”, December 18, 2006, CNN.com

A friend of mine recently introduced me to The Tapes Archive’s excellent YouTube film essay adaptations of Quintin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation, and I specifically have been thinking a lot about the chapter on Dirty Harry recently. In this video, Tarantino counters liberal criticism of the film as fascist, but he offers one concession, saying “the only scene that truly qualifies as fascist is when Callahan tortures Scorpio to find the whereabouts of the kidnapped 14-year-old girl”. If we take that standard to mean that films are fascist when they convey torture as effective, then the Phase I Saw films are clearly fascistic. What makes Saw strange, though, is that the “function” of the violence is construed so differently. In Dirty Harry, the violence is presented as useful to the law-abiding population. But the violence in the first Saw is presented as useful to the victims themselves; confronting death is clarifying and motivates them to get their lives on track.

$4.4 million vs $14.1M, though the comparison is confounded somewhat by inflation and more meaningfully by smaller box offices overall.

That would make them “Gen R”, which admittedly sounds much less cool.

There are certainly implementations of “sharia law” that don’t align with my own beliefs; I’m not suggesting unqualified support of other textual traditions, and there are certainly differences in how text traditions operate across cultures, but I generally try to contemplate broad textual traditions outside my personal experience with a similar open-mindedness to those closer to my personal experience.

All this said, Omar Khayyam seems to have taken the triangle from an earlier Persian mathematician Al-Karaji, but nobody calls it Al-Karaji’s Triangle. And while Pascal may not have been the first to come up with Pascal’s Triangle, Wikipedia does claim he developed “the first modern public transit system in the world”, which seems to be a largely semantic achievement (“modern”?) but still one I respect. I attribute two significant shifts in my political identity to transit policy, and I try to take a bus or train in any new city I visit.