A Case For A Sad Holiday

and: Facts That Care About Your Feelings

Happy Autumnal Equinox, Readers!

I know you just got a long email from me, but I’ve had September 22nd marked on my calendar for quite a while to make the case for a new holiday. (We’re going through a bit of a holiday phase here it seems!)

In my work with a couple wellbeing nonprofits, there’s lots of activity around the International Day of Happiness -- a holiday the UN declared in 2012 that is observed on March 20th. You are probably thinking: “March 20th! Why, that’s often the Equinox!” And yes, though your time zone may cause it to be occasionally on the 19th or 21st, you are generally correct!

Middling Content loves the equinox, because it is the day when everyone gets the same length of day. It is a shared experience in a world that does not have many shared experiences. And if the Spring Equinox is the International Day of Happiness, then it must follow that the Autumnal Equinox is its emo cousin. For starting about 10 hours ago, roughly 81% of the world transitioned the half the year where nights are longer than days.

Though there has not been a UN resolution to declare it, I like to think of today as “The International Day of Despair”. “Blue Year’s Day”, “Dearth Day”, “Cryday”, “Blahlloween”. You get it. We have so many days to be happy together, but no days to be sad together. And so we often end up being sad alone, which is such a drag.

This is not, to be clear, a new idea. Around the northern hemisphere, the autumn has holidays that have us reflect on our night times. In China, the Hungry Ghost Festival was a couple weeks ago -- it marks the last full moon of the summer, a harbinger of long nights. The “Ghost Month” spans from the new moon before and after the festival, so it just wrapped up on Saturday. Though the concept of the “hungry ghost” is originally Buddhist, the Daoist adaptation of it sees “hungry ghosts” as created from unhappy deaths. So it is, in a sense, a holiday honoring bad vibes.

And of course as pop-up costume aisles are foreshadowing, America is entering its “spooky season”, which is connected with a variety of autumnal traditions in Europe and the Western Hemisphere. When visiting Budapest in 2019 during All Saints Day, the midpoint of autumn, a new acquaintance shared with me how she was heading to her home village to visit her deceased relatives in the cemetery. In Mexico, this same day hosts festivals for El Dia de los Muertes. In what I think is quite thoughtful holiday design, there are separate celebrations for those who have recently lost children and those who have lost other relatives, creating a shared space for sharing sorrows. Meanwhile, the US celebrates the mid-autumnal festival with candy distribution, gruesome displays and looping “The Monster Mash”.

Having shared days of mourning to deal with difficult feelings helps to normalize them and provide support, and they help struggling people find each other. I don’t know if Autumnal Equinox is quite the right fit, but I’ll try to make an effort to use this writing project on this day to focus on topics of struggle.

Though we don’t have a shared day like this, I suppose I just want to remind everyone that tough times are a shared part of the human experience. And I do think that pain that teaches us empathy while also encouraging us to spend some time in our hearts, reflecting and growing.

The assignment I’ve given myself today was to critique that old saw, “Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings”. It has been done in a few places, but I have some of my own thoughts.

I will make the following three points:

The Implicit Understanding of Facts is Flawed

Everyone Cares About Feelings

Thousands of Feelings Facts Exist

These points together will, I hope, make the case that the phrase should be retired.

The Implicit Understanding of Facts is Flawed

To some degree, I suppose some would say that “facts don’t care about feelings” in that facts don’t care about anything. And there is some truth in this. Facts don’t feel; people feel.

But I think this misunderstands facts in two ways: (1) it treats estimates as facts and (2) it incorrectly anthropomorphizes them.

Most “Facts” Are Estimates

I used to work at a large TV Ratings company that spent lots of money creating and operating a system to measure media viewership. The statistics are very valuable to companies who buy or sell advertising, and so it’s important that the statistics are only available to those who financially support the measurement ecosystem.

A possible concern about a business like this would be that intellectual property law doesn’t permit copyright protections for facts; “facts” are public domain, encouraged to be spread to support education and future research. And so how can such a business make money? The business was able to operate sustainably for decades because it differentiated between “estimates” and “facts”. And most of what we think of as facts are actually “estimates”.

In his article “Three Theories of Copyright in Ratings”, law school professor James Grimmelmann breaks down the difference between ratings as “facts”, “opinions” and “self-fulfilling prophesies”. Courts have found ratings to be protectable “opinions” if they are labor-intensive, expertise-driven or creatively-designed.1

When people speak about their sense of the Truth, these feelings are often drawing upon estimates -- like TV ratings, coroner’s reports -- that rely on particular methods from a particular perspective. It’s often complicated that most purveyors of “estimates” try to position them as “facts”, as facts are higher-status and more monetizable. But alas, it’s just marketing.

Opinions have lots of feelings, of course. The facts themselves wouldn’t adjudicate these sorts of matters.

Facts Won’t Tell You What To Value

The semantic construction of the phrase “facts don’t care about feelings” is also inherently misleading.

By specifically calling out “feelings”, we are being asked to anthropomorphize facts -- poetically imagining them as caring about some things and not about others. (The addition of “about feelings” would be superfluous otherwise.) And this idea seems misconstrued. Facts are neutral arbiters, but they require people to make judgements.

A Fact, if it were a human, would be the sort of human that cared only about Truth in itself.

I think in some regards, I feel a sort of kinship with this Fact-as-Person. In part because, as a professional researcher, it is my vocation and calling to seek Truth, a pursuit I’ve engaged in for over a decade now. But also because, when I was 25, I was diagnosed with OCD.

OCD is very publicly misunderstood. Many folks are familiar with the excessive handwashing that can cause a person to scrub their hands so hard they break skin. I’ve never been an obsessive handwasher.2 I think of my experience with “OCD” as an experience with “pathological skepticism”. Or put otherwise: I had a deep hunger for certainty that was fundamentally unresolvable.

Understanding OCD has been helpful in me thinking differently about how Facts and Truth operate in our lives, so I’ll give a quick overview.

A Brief Overview of OCD

The handwasher persona can be a helpful illustrative guide to how OCD functions. Someone can see a person handwashing obsessively, and they imagine it as a deep drive toward cleanliness; as I understand it, a person with OCD is more driven away from disease and infection. “But aren’t all people driven away from disease and infection?” Indeed, but some people don’t think about it; some people just have a phobia that leads them to avoid hospitals or countries on the CDC advisory; those with OCD are not capable of feeling “certain” that they’ve removed the germs from their bodies, and thus will do harm to themselves in seeking that certainty. Where many would get a feeling of “cleanliness” or “sufficiency” from washing to their 20-second song of choice, someone with OCD is denied that sense or feeling. While OCD is seen as moving toward something, it is felt as being starved for a kind of epistemological clarity.

This “certainty-seeking” behavior is what differentiates having OCD from just being someone who likes things organized. My obsessions were of the “pure-O” type, which meant that I would be drawn into self-reinforcing thought loops, mostly of the “existential” subtype. What that meant is I would become gripped by mundane philosophical questions, like “what if this is all a dream”, and I would desperately think as hard as I possibly could, trying to think myself out of distress while ironically escalating it substantially.

I’m generally not always a fan of classifying unique modes of thought into pathological categories, but I did find that “CBT” and exposure therapy were helpful. I had to learn to not feed this hunger for certainty; that hunger only deepens once you let it chase shadows through the labyrinth of your mind. We have agency! And we can learn to say no!

Part of what helped me was learning that Descartes’, in the life he led leading up to his “cogito ergo sum” revelation, had a series of nightmares one night in 1619 when he was a mercenary in the Thirty Years War. I even went to a series of lectures on the anniversary of these nightmares -- which I think of as the panic attack that launched Modern Philosophy.

When I first read Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy in college, I honestly found it deeply unsatisfying. I still sought Truth as my primary goal, and his reliance on faith at the end felt like a cop-out. I don’t agree with his entire process and with the particulars of his solution, but ultimately I do agree that we must choose to ignore certain deep philosophical questions in order to operate as “healthy” adults.

It still seems counterintuitive to me that “healthy” psyches can ignore such blatant risks and concerns. People with “healthy” psyches do indeed occasionally miss germs when washing their hands, and sometimes those germs take root and kill them. People with “healthy” psyches occasionally leave the stove on to burn down their apartment killing innocent people. People with “healthy” psyches are wholly unconcerned with whether or not they are living an inconsequential life in a meaningless dream. This is because what is “healthy” is not the relentless pursuit of certainty. Life is so rich with mysteries, and so we must pick and choose which to chase to advance our broader human dreams.

It is typical for many people that go through a therapeutic intervention that reshapes their cognition, and then to see their pathology everywhere in the world. This is often unhelpful. But in this case, I do think the analogy is useful. Seeking Truth as an end to itself leads to unbalanced and unhealthy psychology.

If a Fact were a person with feelings, it would be overly obsessed with minutia and incapable of functioning in a healthy way. It would be no guide to anyone. A Fact serves its function within the broader context of human judgment.

As humans, we have a responsibility to see the broader context of things. We set the plan and use facts to navigate to our goal. And that requires us to see certainty as not just a logical abstract state, but as a feeling that occasionally is denied to us through unpleasant neurochemistry.3

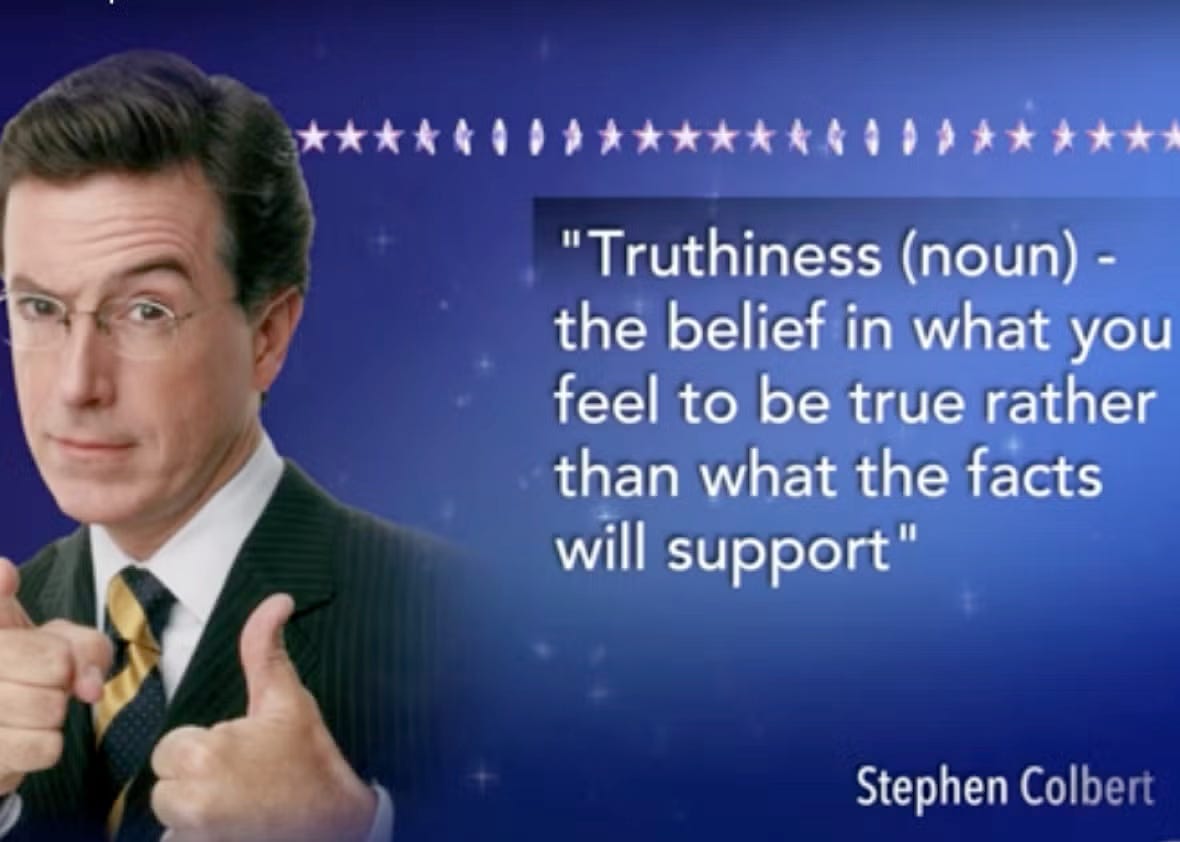

Truthiness as a Nicomachean Virtue

I, like many college students of the late 00s, found the Colbert Report brilliant and delightful. One of the most famous coinages from the program was the concept of “truthiness”, which would describe the “feeling” of truth that may not even be true. It was the focus of his segment “The Wørd” in the program’s pilot episode in 2005, when it was increasingly clear to Americans that the intelligence that led to the 2003 Invasion of Iraq was misleading. In that context, “truthiness” was obviously a troubling and dangerous idea.

I do think, though, that seeing “truthiness” as always bad can be troubling as well. As I’ve gone through life deciding exactly how much time and energy to spend on truth-seeking versus other pursuits, I think there is a less explored antonym of “truthiness” -- perhaps called “truthinesslessness”.

Aristotle famously saw the good life as one of balance. Too much courage and we are brash; too little and we are cowardly. Similarly, I think too little “truthiness” can disconnect us from our humanity. When we see college campuses as spaces to throw our facts in the ring and see them fight each other like Pokemon, we miss how they are also spaces where people learn to connect with each other as a community. Our Facts don’t have to be weapons; they can be tools to build our shared environments.

You can’t survive on Facts alone; you have to care about other things.

Fortunately, pretty much everyone cares about other things.

Everyone Cares About Feelings

Feelings are a huge part of how people experience the world, to the degree where it’s almost tautological.

We like to feel good. We don’t like to feel bad.

And it’s something observed across geographies, across politics and across interests.

Americans Are Particular Feelings-Oriented

For those in America, it’s within our founding sense of human liberty. The right to pursue the feeling of happiness closes out the first sentence of the second paragraph of the US Declaration of Independence. Other countries have adopted happiness as an objective too, most notably the Government of Bhutan with its Gross National Happiness concept.

When we meet each other, we check in on each other’s wellbeing. In Singapore, where I spent most of my teenage years, the local greeting was more practical, asking “Have you had your lunch?” This was an anglicization of the Chinese greeting “你吃饭了吗?”, which I have always assumed gained deep meaning to generations that survived periods of brutal starvation during the Great Leap Forward famine. When visiting Croatia, I remember learning that a common greeting is “Jesi živ(a)?” or “Are you alive?” Here too, one can speculate that tragically harsh historical conditions shape pleasantries.

People who visit the Anglosphere from other countries are surprised at how feeling-oriented the culture is. Rather than asking about wellbeing from a purely material sense like the Chinese or Croatians, we allow the interrogated to interpret the greeting “how are you?”. Visitors will sometimes misunderstand the question to be a deeper probing of sentiments, but practice is more to signal interest in the feelings of others before moving into other topics of conversation. And if you’re in the Beverly Hills of 90s film Clueless, teenagers have the emotional sophistication to respond to petty annoyances by asking “what’s your trauma?”

There is a sense within the United States it is only the Left that concerns itself with feelings, but that seems to me to be not true.

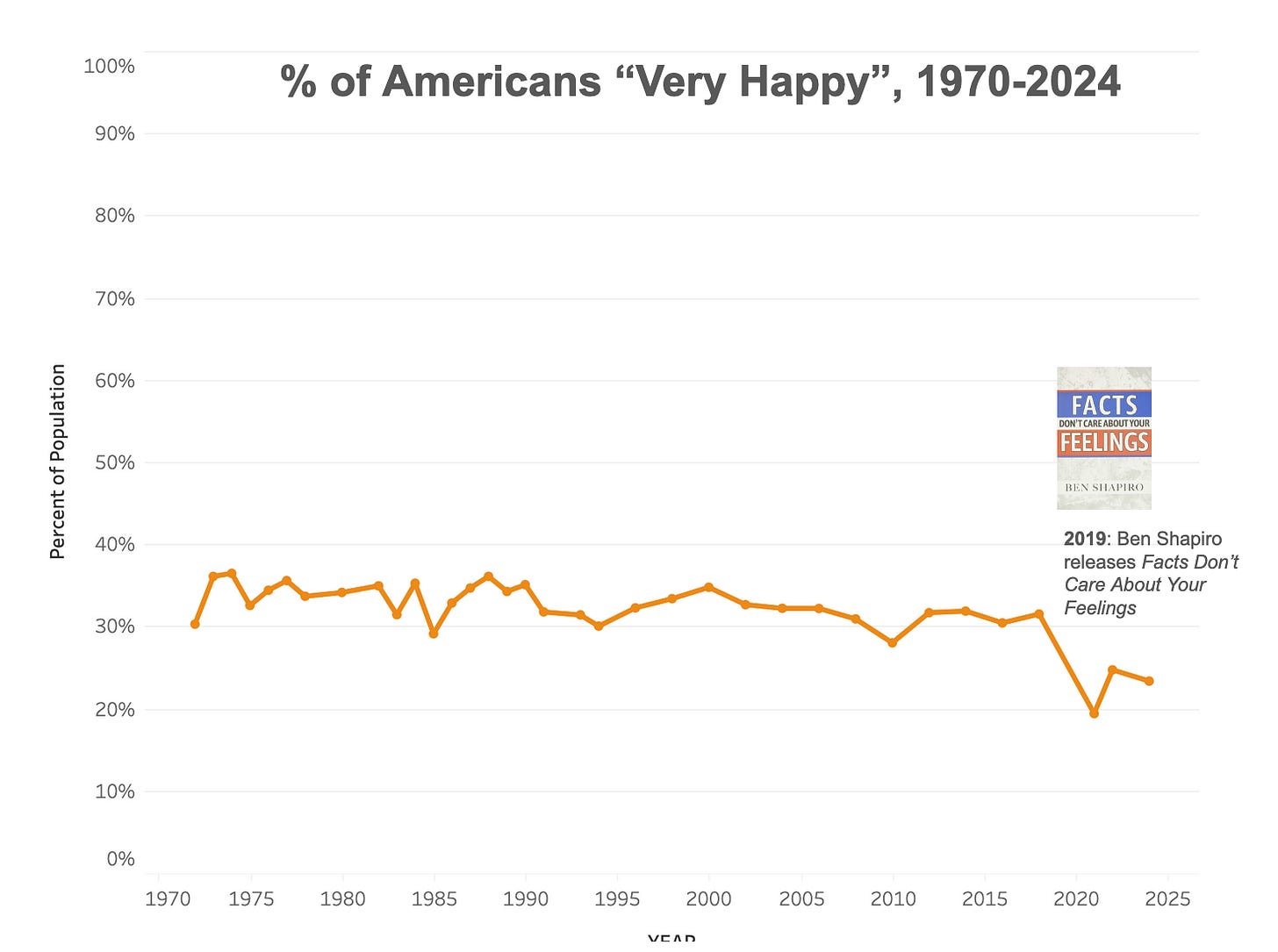

Conservatives Care About Feelings Too

The person I most associate with the phrase “Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings” would attend high school in Southern California a couple years after Clueless came out. I wonder if Ben Shapiro saw it in theaters?4 His 2019 book, Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings, was named after the phrase that he helped make popular. It was such a success that in 2020 he released a sequel Facts (Still) Don’t Care About Your Feelings. I’ve not read these books, but I have listened to a few episodes of his podcasts in perhaps 2021, mainly as part of a project trying to understand how right-wing media criticism is different from left-wing media criticism.

Most of the news it felt like his program was covering at the time was in fact talking about the media environment, which was something that I think was also increasingly common on the left. Everybody was operating with a “clip show” style that I think was first made famous by The Daily Show. The format is highly replicable, and in some ways social media feeds that use shares/replies/stitches are just algorithmically curated clip shows.

Regardless, it’d been a few years since I’d last heard him, as I had felt that a few episodes was enough for me to understand his format and take, which I took to largely align with what academics call “elite capture”. It’s in broad strokes the same theory that motivates the Fighting Oligarchy Tour; the examples that the populist right selects to make the point are just more centered around cultural issues rather than class issues.

Talking About Feelings Without Talking About Feelings

That said, I do think hearing him speak on The Ezra Klein Show5 about his new book Lions and Scavengers gave me new insight on his politics. Lots of seemingly prolific program hosts rely on a format, and the clip show format is commonplace largely because it lends itself to factory-style production that isn’t too taxing on hosts; a couple interns can find a bunch of clips online, and a producer can boil down the list to a few pieces that the host can respond to more-or-less in real time.

The new book fits his typical anti-feelings framing with a taxonomy of “Lions” and “Scavengers”; “Lions” bravely defend noble ideals of a healthy and good society and “Scavengers” are false prophets who exploit ego, resentment and hedonism to gain power. Unsurprisingly, the Scavengers play to feelings whereas the Lions somehow transcend that style of politics.

To his credit, Shapiro does acknowledge that many of Trump’s policies align him with Scavengers, though he suggests that politicians can scavenge a bit without going full-Scavenger. It’s unclear to me how much of this is his genuine take versus hedging to avoid retribution from the current administration; he also could be just savvily positioning his ideology in a way that will sell more books to Ezra Klein Show listeners.

The part that interested me, though, was a part that, to me, gave me a better sense of how “feelings” fit within the Shapiroean vision of Lion-led society. Klein observes that the Lions are positioned as defenders of “Western Civilization”, and so he asks him to define Western Civilization.

The definition he provides is narrow yet pluralistic:

The way that I describe it in this book, and I give a sort of more fulsome definition in an earlier book that I did called “The Right Side of History,” is the tension between Jerusalem and Athens. Not my original construct. That’s a division that goes back to Tertullian.

The idea of a biblical heritage combined with Greek reason and the tension between them. They don’t easily fit together. And so what you see over the course of Western history is this tension. Sometimes it moves in the direction of biblical theocracy, which you can see in European history. Sometimes it moves more in the direction of reason.

But if either comes on more than the other, you end up with a pretty bad thing. If you end up with, like, a full biblical theocracy? Bad. If you end up with a fully amoral, rationality-based system? Also bad. Which is the history of the mid-19th to mid-20th century.

And so the history of Western civilization is the symbiosis between those two factors. But the basic principles of Western civilization that I think are the most important, at the very least that I discussed in the book, are things like equal rights before the law, private property, freedom of mind, freedom of thought, freedom of religion.

The balanced tension between reason and religion on one level avoids reference feelings explicitly, and yet both reason and religion are blissful pursuits. In a Freudian sense, reason plays to Lebenstrieb (“life drive”) and religion plays to Todestrieb (“death drive”); one provides the delight of agency and the other the delight of submission. Shapiro overstates the unique Western heritage; before the times of Socrates, the Dao De Jing Chapter 28’s endorsed of balancing the agentic 雄 (“xióng”) and yielding 雌 (“cí”).6

There are certainly politicians that scavenge on feelings on both sides of the aisle. An appeal to the ego of his “Barbarian” archetype will resonate with White Savior types on the Right and with Social Justice Warriors on the Left. An appeal to the resentment of his “Looter” archetype can exploit class regardless of party, with the Left dividing on income brackets and the Right dividing on educational attainment. An appeal to the hedonism of the “Lecher” archetype will resonate with the wealth-obsessed on the Right or with the sex-obsessed on the Left. But both parties also have many people who delight in thoughtful action and community participation, even as I’m sure opinions will vary on the validity of egoism, resentment and hedonism as pleasures to pursue.

So to me, the main face of the contemporary “Feeling-Nonaligned Movement” has a place for feeling within his ideology, though he does not name feelings directly. And I think his frustration with the Left is more driven by a lack of shared narrative through which to communicate. And because he’s drawn a semantics-grounded boundary, it’s hard for others to break through.

An Alt-Right Appeal for Feelings Conscientiousness

I’ve said it many times in this newsletter, but my goal is to help people create a media diet that “middles”. I specifically try to engineer for myself a globally oriented content diet that spans the political spectrum. With podcasts, that usually looks like Blowback on the populist left, Pod Save the World on the institutional left, The Intelligence (from The Economist) on the institutional right, and History 102 on the populist right.7 I round that out with reading a few of my favorite publications: The South China Morning Post, The Hindu and Al Jazeera.

I share that because it just so happened that the Rudyard Lynch, who co-hosts History 102 and runs the Whatifalthist YouTube channel, is not someone I’d listen to if I were only seeking out content that affirms my current worldview. There is a great deal that disagree on, and he does occasionally get facts wrong without issuing corrections, meaning anything I hear from him has to be independently verified. He does connect me with new historical examples and also synthesizes and critiques narratives in a way I find strengthens my own thinking. To me, listening to people discuss history is similar to how I think about listening to jazz, and I’m curious to hear people riffing on a shared collection of stories and ideas. Also, Lynch is a 23-year-old and the only person a decade younger than me that is in my information diet, which I think is important in a world where young men’s worldviews diverge meaningfully from my own.

Obviously people listen to arguments in different ways, and while I think consuming a broad range of ideas has benefits, I respect that most people lead busy full lives that don’t give them the energy and patience for this kind of thing. Citations are never endorsements unless explicitly stated. My goal is to design an information diet that reflects the world, not to curate one that reflects my own tastes and values exclusively.

This is all preamble to share that Whatifalthist posted a video titled “why empathy is the meaning of life” yesterday, which within his own definition of terms, defends empathy as a value and offers his perspective as an anthropologist. I will warn that I think most people I am friends with will dislike almost all of the video, as it uses phrases like “woke tyranny” unironically, presumes his listeners share his specific conservative gender ideology, and makes claims like “it’s obvious the Left is totally incorrect and mentally ill”. Again, he’s 23. He’s willing to read extensively, break with orthodoxy and construct his own theories, and I’m interested to see how his thought continues to develop. And he’s an advocate for EMDR as a PTSD treatment, which I think is a nice thing for his young adult male audience to hear. (Honestly the part that triggered me most was when he was praising Bismarck, who I had framed as a major enemy in my recent Haymarket Affair article.)

So if a self-proclaimed “constitutional conservative” like Ben Shapiro cares about feelings, and a more MAGA-flavored Gen Z conservative like Rudyard Lynch cares about feelings, it’s clear feelings can be central to the American Right. But to make one more point, I think it’s important to draw in the central figure of the contemporary right.

Ave Maria and Permission to Feel

It feels deeply intuitive to me that the figurehead of the populist right right now, Donald Trump, is the most id-driven vibes-based politician who has led the country in my lifetime. (In order: Trump, Clinton, W., Biden, Obama, H.W.) His ability to feed on the energy of crowds is quite unique, navigating their feelings while also delighting in the process.

For me, the quintessential Trump feeling video is the roughly 3½-minute segment of him vibing to “Ave Maria” in the middle of a rally. For those who intensely need to win and dominate in every interaction, the arts can provide an outlet to the part of our soul that yearns to yield.

So it seems obvious that feelings are central to the right as well as the left; they just conceptualize them differently. I think Shapiro’s feelings palette with three corrupt drives (ego, resentment and hedonism) and noble drives (reason and community) can show how good and bad feelings are central to both political projects.

Still, a major challenge is perhaps convincing conservatives why they should care about other people’s feelings, and I think the Tertullian Athens-Jerusalem axis can potentially be of use here too.

Feelings are in Everyone’s Interest

Even if one isn’t concerned about feelings in themselves, one is certainly concerned with factors downstream of feelings.

If all you care about is captured within the Tertullian framework, as noted Feelings-Disregarder Ben Shapiro puts forward, then it should be enough to get you to care about feelings if positive feelings support a society’s treatment of reason and of religion. So let’s handle each of those in turn.

Feelings Support Society’s Capacity for Reason

Education is one of the nine domains in the Bhutanese framework for Gross National Happiness, and many people associate their wellbeing with the freedom to pursue independent intellectual pursuits -- free through, free speech, free assembly, etc. But what about the reverse? Does increasing the wellbeing of a society make it more friendly to reasonable living?

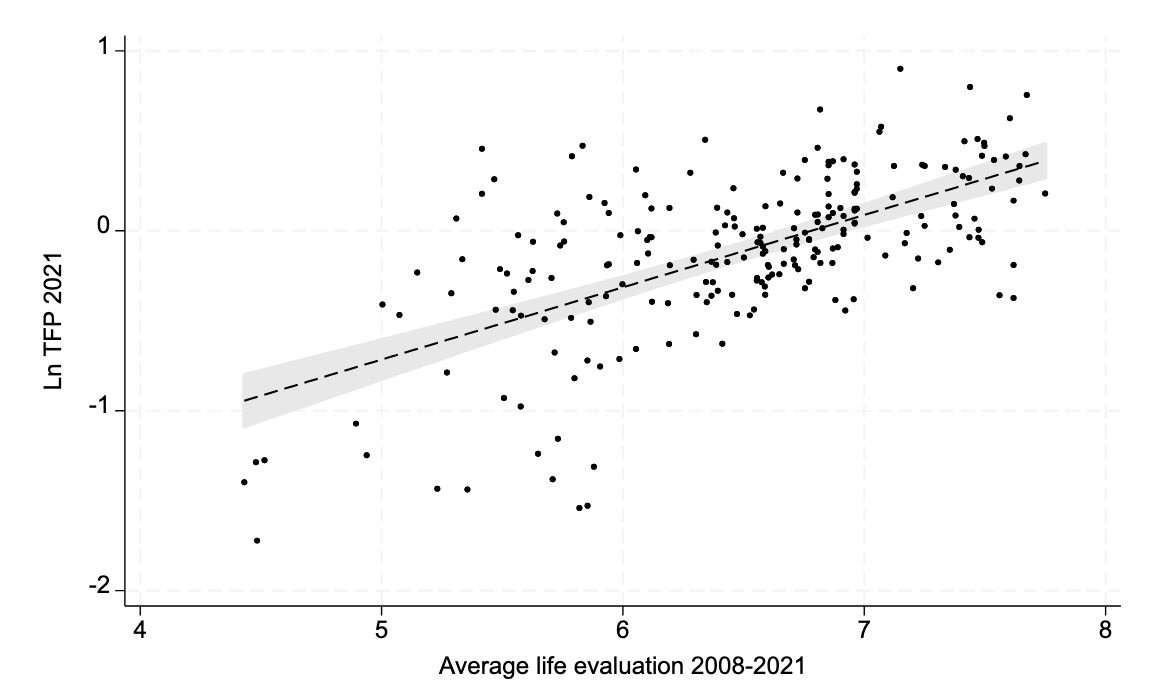

I’m a member of an organization called ISQOLS (any politics expressed here are my own), which is a consortium of researchers that investigate questions of wellbeing. There’s intense debate about how to best measure these concepts, but a common measure is called “Subjective Wellbeing”, or “the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his/her own life-as-a-whole favorably”. Some colleagues of mine recently published an article comparing self-reported life evaluations to Total Factor Productivity, a common measure of economic output.

To some degree, we can see creative and productive activity as a reason-oriented activity. It emphasizes agency, Lebenstrieb and xióng, acting on the world to create a desired future.

While that study does time-order variables to assess some level of causality, it’s not experimentally evaluating this effect -- but that’s just a paper from my own personal network!

Looking more specifically for direct impact on reasoning, we can find a 2001 literature review that finds studies where positive affect increases cognitive flexibility, creativity and efficiency.

All this while stress, on the other hand, has been shown to be detrimental to the pre-frontal cortex. This is observed in experimental settings where participants are randomly assigned a stress-inducing task like public speaking, and then their working memory and cognitive flexibility are testing -- and both show degraded performance.

So if you care about maintaining an Athenian society of reasoning, you also implicitly care about feelings! A society that feels bad will reason poorly!

Feelings Can Support Society’s Capacity for Religion

This is admittedly a bit more mixed as an effect. People can seek religion in trying times, which is actually a useful counter-cyclical response since religious participation tends to increase wellbeing.

But there are some documented cognitive effects of note, particularly on how wellbeing can in some cases increase open-mindedness and therefore religious tolerance. This was noted in a study with physicians where they

And one study found a particular kind of wellbeing, the loving-kindness sort, to reduce biases on implicit attitudinal testing.

This means that those who value religion might prefer to live in a society that is feeling-forward.

Literally So Many Facts About Feelings Exist

The clearest case for facts being at least occasionally concerned with feelings is the wide range of statistics about feelings that are easily available to anyone online today.

To say there are no facts that care about feelings is demonstrably false. Let’s walk through a few different examples.

The World Happiness Report (link)

This annual study, run by Gallup in partnership with a wide range of nonprofits, provides happiness measures for 140 countries. Finland has been the happiest country since 2018. (Honestly, I’m skeptical.)

CDC Mental Health Household Pulse (link)

The US government reports on levels of depression and anxiety on the CDC website; this data comes from the National Center for Health Statistics and breaks out by state and other key demographics.

OECD’s “How’s Life?” Report (link)

An investigation of what factors drive wellbeing in the 40 member countries in the OECD. It specifically calls out that people are struggling with financial wellbeing in particular, driven largely by increasing costs of housing.

GSS Data Explorer (link)

The General Social Survey, running out the University of Chicago, has been asking a happiness question to Americans every other year since 1970. Happiness levels show a slow three-decade decline, with a sharp decline in 2020 that has not yet recovered.

WHO Global Health Observatory Dashboard (link)

An interactive map of depression prevalence around the world, plus the Global Health Observatory has an API with a wider range of metrics to access and analyze related to mental health.

And this is just broad public datasets. Lots of smaller-scale independent research takes place as well in academic institutions. I track publications of studies that investigate the connection between media and wellbeing, and my tracker tells me that in the past week there were 480 papers on that topic. (And that’s down from 673 the week before!)

The previous administration’s Surgeon General released a 2023 report declaring a “Loneliness Epidemic”. And the current US Secretary of Health and Human Services explicitly called out making government data on depression more visible to policymakers in the White House.

The current Health Secretary’s operating model of wellbeing-creation may focus more on food dye than mine, but ultimately he’s decided to elevate facts that care about feelings. Putting aside other policies, this is constructive.

I even have collect my own facts about feelings. I personally have collected 25,000 interviews about feelings in a survey platform I built a few years back, and then I use LLMs to break them out into word embeddings, which break each feeling fact into 3072 components, so that’s like 76 million feeling facts. I’m on the board of an organization that stewards video interviews with people all over the country, talking about what matters to them in life and why. I analyze my journal entries to evaluate drivers of my mood, and I know others who use apps to track their moods over time.

There truly are a mind-melting quantity of facts that concern themselves with feelings.

Fighting Despair Together

I am continuing to build out my survey platform Mic Check Media, and if you have any interest in supporting that work, you are able to sign up at www.miccheck.media. I will give 10% of my profits to a blend of ISQOLS, GNHUSA, Samaritans and NAMI; these are all wellbeing organizations I’ve interacted with at some point and can vouch for, but the politics in this post is merely my own.

If folks want to help but don’t want to subscribe to Mic Check, I am happy to provide another option. I don’t want to force people into the subscription-industrial complex. If you just want to support directly you can Venmo me at @Eric-Brisson. As a disclosure, Mic Check is not a non-profit, but the 10% of your donation that goes to nonprofits will be tax-deductable.

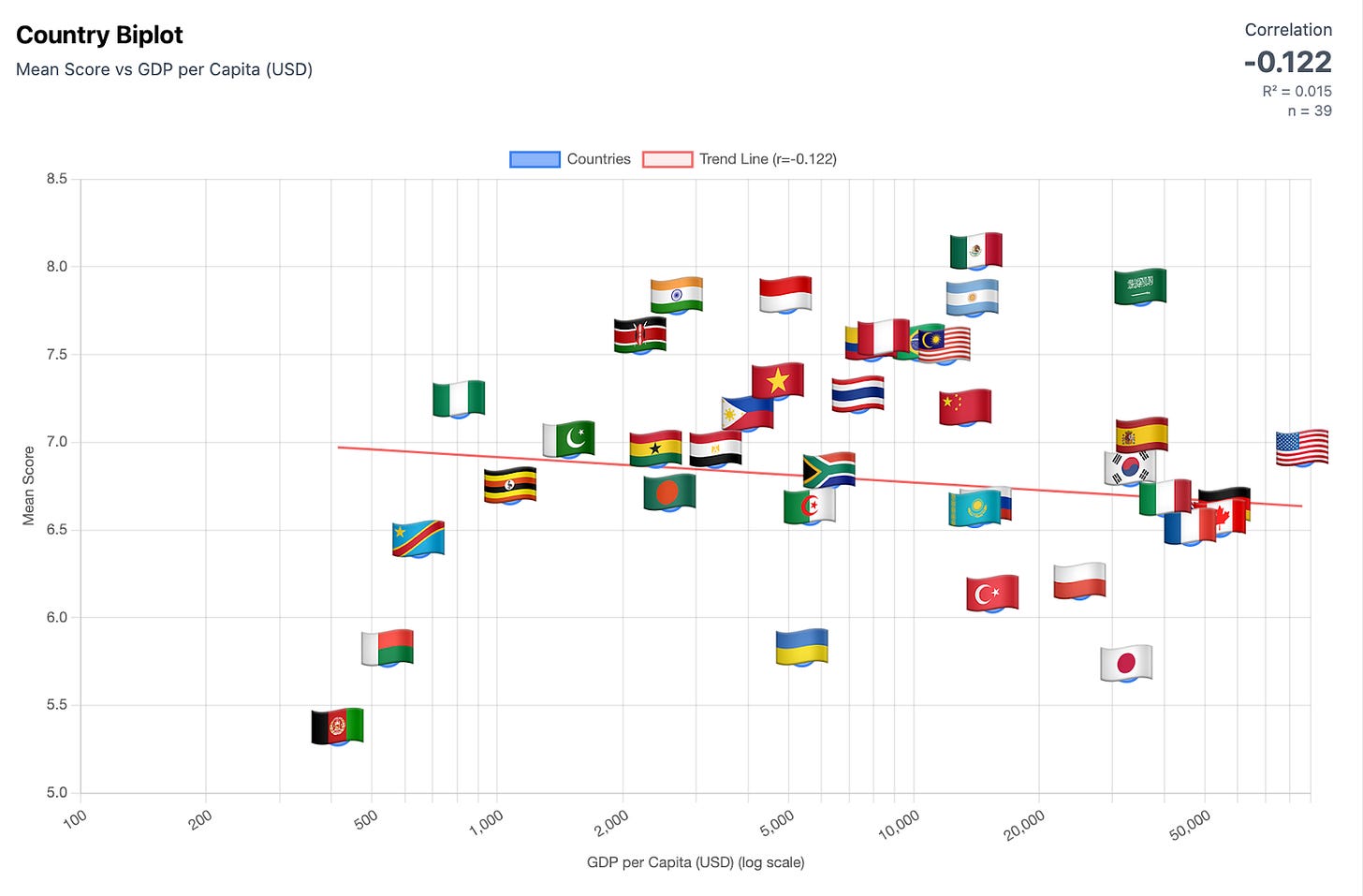

Above is a biplot I created in Mic Check. If I’m reading this biplot right, then income (proxied by per capita GDP) is negatively associated with happiness, so maybe that means you will be happier the more of your income you give to Mic Check? That is not a guarantee. Could be worth a try through?

No matter what you decide, I’m wishing all an emotionally rich and thoroughly cathartic International Day of Despair.

Your Brother in the Struggle,

We’re Never Alone,

Harry

Disclosure: I’m very much not a lawyer! It also does seem on further research that the stronger legal reasoning that prevents the sharing of data is contractual obligation; perhaps this is why I still see TV ratings data on program Wikipedia pages.

It’s fair to say nobody I’ve lived with would describe me as even moderately organized.

Disclosure: I’m also not a doctor! If you think you are struggling with OCD or any other issue, please reach out to a professional! I also expect our taxonomies of psychology as well as our understanding of them will evolve significantly with time, so it’s okay if you don’t strongly identify with terminology!!

He’s also cousins with Matilda from Matilda, which would come out the following year.

I know Klein has been taking a lot of flack for his comments where he identifies with a broader “public intellectual” movement that includes people who I would argue treat discourse very differently than he does. I think his interview with Shapiro, which was recorded before political violence became a central topic in the news, is more persuasive . My favorite Ezra Klein episode was the Vox series finale before the show moved to NYTimes, where he gets specifically into his theory of media -- largely that it’s an act of McLuhanian praxis attempting to model decency and highlight humanity even within disagreements.

There’s a gendered quality to this verse that I don’t really center in my reading, but it’s something you may encounter if you discuss it with cultural conservative Daoists; Shapiro might actually be more interested in that reading, though.

Recent political realignments do make me wonder if I should be grouping things differently here, as the difference between Pod Save the World and The Economist is less clear to me than it once was.

Abounding with interesting thoughts (as always), and good luck continuing to walk the Tertullian knife’s edge.

In terms of “sad holidays”, may I suggest Yom Kippur? 😉