Happy Belated May Day!

or: How I Spent My Summer Vacation

Foreword / Editor’s Note

I originally intended to write a short reflection this past May Day, and most of you received an earlier draft that was rescinded because immediately after I sent it I could tell it was incomplete. This draft is not perfect either, but I do think it at least better contextualizes its central question as compassionately grounded and better answers it.

Since the prior release, these are the main adjustments I made:

I read a broader range of primary and secondary sources that I link at the end of this email, correcting my own sense of the history and, in at least a couple cases, correcting Wikipedia’s as well.

I designed, deployed and analyzed my own global survey of thousands of respondents about May Day associated policies, much of which is referenced only briefly.

I traveled to a few key cities relevant to the Haymarket Affair’s origins, trying to understand the narrative at a human scale.

I added more info on historical context, included more background on the key characters, deepened the existing timeline, added narrative analysis and conclusions, and all-in-all over quintupled the length of the essay.

I know this is mainly a space where I share intermittent updates with friends and family, so please feel free to just skim headers and/or pictures. You can think of this as an optional draft that I’m sharing with you, and I will likely revise this to share on future May Day(s), so I am open to hearing likes/dislikes.

You may have feedback like “don’t use the word anagnorisis so much” or “stop spreading disinformation about the Chicago flag”. The only feedback I won’t incorporate is criticism of the historical present tense. Spellcheck really hates it. And clicking “ignore” when it gets triggered is a small way I assert my humanity and fight the rapid technological erosion of the storied craft of storytelling.

…And do you know who else was futilely resisting rapid technological dehumanization of their labor? (That’s as good a segue as we’re going to get, I think.) Skim away and you will find out, dear reader!

Have a happy May Day, no matter what month you find yourself in.

In Your Inbox,

Harry

How I Spent My Summer Vacation

Happy Waning Day(s) of Summer!1

While most of my readers are friends and family in the US and Canada who wrapped up their Labor Day Weekends this month, I’m currently in Istanbul where they observed a completely different holiday that same weekend. Turkey instead celebrated Victory Day, which commemorates their victory at the Battle of Dumlupınar in 1922 which set the stage for the end of the 623-year-old Ottoman Empire. There’s something kind of cool about a country celebrating the end of their own empire.2

Turkey celebrates Labor Day too, of course, but they did it back on May 1st. Indeed, in most of the world's countries, Labor Day is celebrated on May 1st. And that’s not a plurality or driven by many small countries; May 1st is Labor Day for a full-on majority of people on the planet. Over two-thirds of the world’s population live in a country that celebrates Labor Day on May 1st. The explainer map on Wikipedia is so steeped in deep socialist red for May-celebrants, it has the aesthetic of a Reagan-era war game rapidly approaching checkmate.

This map in some ways overrepresents American counterprogramming to May Day:

The UK is engoldened to remind us that even though its “Early May Bank Holiday” overlaps with May Day septennually, it does NOT identify as May Day.

Australia’s green coloring is somewhat misleading, as their provinces independently choose when to celebrate labor day, with Queensland and the Northern Territory in the same; the Northern Territory’s holiday is explicitly called May Day.

Though Denmark and Greenland are gray on this map, the Scandinavian nation and its territory tend to follow the rest of the EU and give workers at least a halfday.

This map is from 2020, when Afghanistan was still US-occupied and there was no celebration of May Day; after American withdrawal from the conflict, Afghanistan seems to celebrate May Day again.

But putting aside the scheduling disagreement for a moment, it’s remarkable to note the widespreadness of Labor Day celebrations as a whole. Truly global holidays like this are actually somewhat of a rarity. If we gave out awards for holidays here at Middling Content, a “Middley” for Most Shared Holiday, how close would Labor Day be to earning that prize?

Middling Content Holiday Rankings

As I wrote about on the Vernal Equinox of 2024, the purpose of this Middling Content project is to reflect on the media's function as a grand societal centerpiece that provides a platform for discourse. A healthy media environment serves the public by providing a common “middle”, connecting people across lines of difference through shared touchstones. Individuals can know they’re consuming a healthy media diet when they have something to talk about in the elevator -- astrological phenomena, local sports and the weather. Such was easier in the days of a small handful of TV and radio stations; when the media fails to provide a common “middle”, people are more isolated and strangers feel further away.

And so when I think about how to rank the holidays, I’m influenced by the question “If not the people then who?”, a 1966 speech given by a man who built and shaped the organization where I learned the trade of media market research. In it, Art Nielsen Jr defends TV ratings with a take reminiscent of Churchill’s “Democracy is the worst form of government… except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”. He invites us to consider alternative approaches to evaluating media, and arrives at the conclusion that indeed a people-centered approach is the optimal method to select programming available to the country.

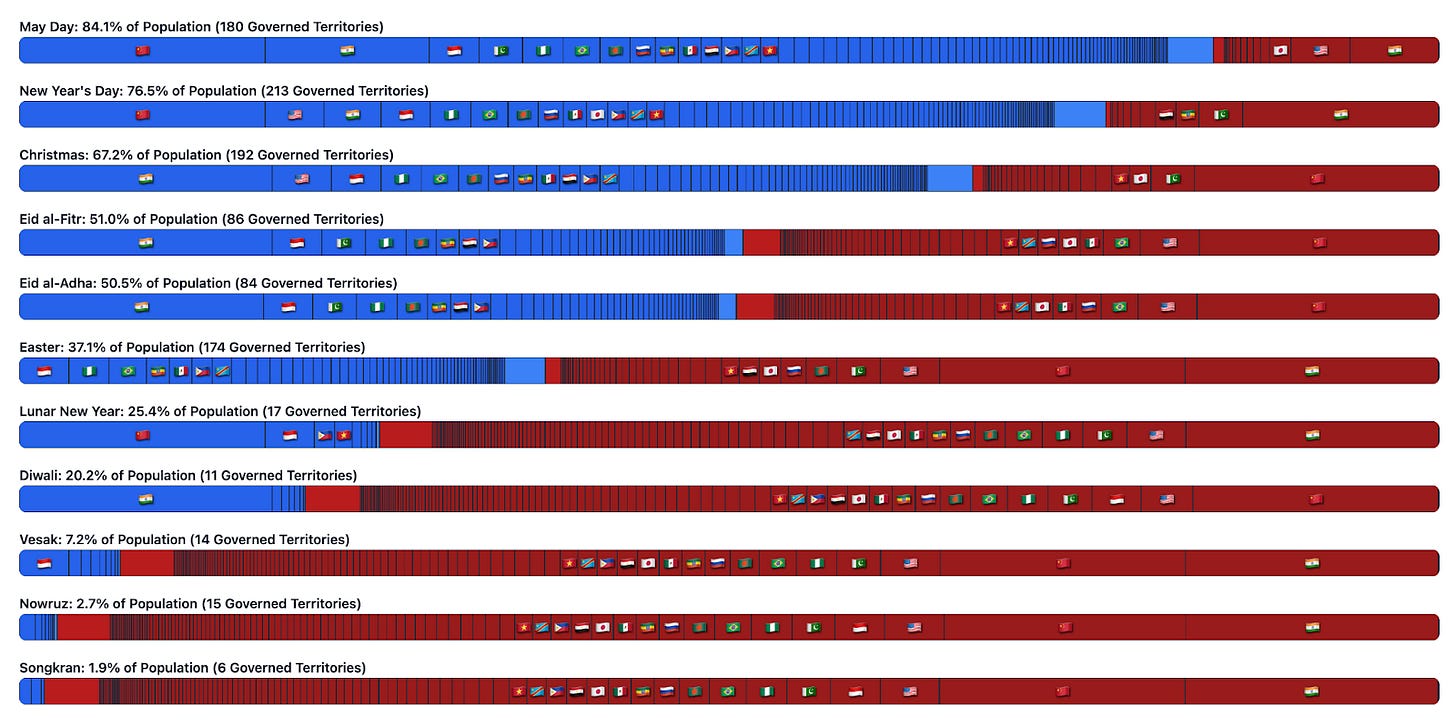

So what holidays win in a raw count of government-directed observation? I collected data on each country and aggregated it to create the following ranker:

It’s perhaps a surprise that the most common holiday, with over 4 in 5 people on the planet in a municipality that honors it, is Labor Day AKA May Day AKA International Workers’ Day. It is bigger than Christmas by over a billion people. And it even ekes out New Year’s Day, that old holiday that gives us an annual opportunity to think about the Roman Empire that established it. Over four times as many people live in a region that recognizes May Day / Worker’s Day than speak the most-spoken language English (~6.8B vs ~1.5B).

Experiences that unite more than half the planet are phenomenally rare, so May Day is really something to marvel at. And indeed I have been marveling at it -- all summer long, from Labour Day (Intl) through Labor Day (US). And I suppose it all started when I decided to make my way into the American Interior and settle myself down in Wyoming.

Some Stats on States & Stadia

About a year ago, when I started centering my life in Wyoming to strongarm myself into getting more serious about writing and entrepreneurship, I was seeking out analogies to comprehend the state’s population. On one end, there are countries with roughly its population, such as Bhutan -- another mountainous landlocked polity that I visited last year. On the other, fewer people live in Wyoming than saw the Eras tour in London. (100k fewer! It’s not even close!)

A series of stadium events would be a great way to meet all the citizens of Wyoming. A dozen meetings with a dozen people each day, you could meet everyone in about 11 years assuming no days off. Too long! While Wyoming’s largest venue, War Memorial Stadium, is only a third the size of London’s Wembley stadium (30k vs 90k), you could introduce yourself to all ~587k Wyomingans in 20 gatherings. Maybe a matinee and a couple evening shows back-to-back?

This is all theoretical, of course. I have a strict “no friends in Wyoming” policy that I’ve been abiding by. I’m confident friends here would disrupt what I see as my life’s “mid-meal sorbet course”. For this sensory deprivation chamber to provide its productivity gains, I must be disciplined. But in theory: if I did want to say hello to everyone in Wyoming in a series of stadium events, and I were not restricting myself to only locally available mass assembly infrastructure, where would be the best place to hold it?

According to Wikipedia, the largest stadium in the world is Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad, Gujarat as of 2020, a year when it would find itself underutilized; with a capacity of 132,000 one could feasibly handle the population of Wyoming in four events. Wikipedia excludes stadia that no longer host athletics, so Prague’s “velký strahovský stadion” is ruled out (capacity 250k), even though this massive space famous for gymnastics could hold Wyoming in merely three gatherings. They also don’t consider motor sports athletics, disqualifying racing circuits like the Indianapolis Motor Speedway (capacity 400k) which could easily handle it in two.

But the reason this exercise has stayed on my mind the past year is not because of the largest raceway nor the current largest stadium nor even the all-time largest stadium. But what sparks today’s newsletter in the twilight minutes of technically-May-somewhere is over a year of reflecting on the name of what was for over 30 years the largest stadium in the world: May 1st Stadium.

It resonated with me because the namesake of May 1st Stadium is the “eight-hour workday” march down that kicked off “the Haymarket affair”, a slice of American history that I’ve always found personally fascinating. I also found it amusing that this established a roughly ten-year period where Chicago both held the tallest building in the world (the Sears Tower) and was a namesake-of-sorts for the largest stadium in the world.

But this stadium named for Chicago’s labor movement is not in Chicago. It’s not even in the US. May 1st Stadium is actually known as 릉라도 5월1일 경기장. It’s on the Korean Peninsula, and not the part that allows Americans 30-day visa-free visitation.

More directly: the May 1st Stadium is in Pyongyang, North Korea.

From a May 1st Parade to a May 1st Stadium

There are really two parts to this journey: first there is the story of what’s called the “Haymarket Affair” which takes place between May 1st 1886 through November 11th 1887 -- a series of events resulting in the state-sanctioned murder of four men in a judicial process the government itself declared as corrupt and misled less than 6 years later.

Then there is “the story of the story”, which carries this tale from Chicago to Paris to Russia to China to Pyongyang, while also seeding the debate for the forty-hour workweek.

I break this out into the following sections:

Preamble: 15 Years Earlier

Part I: The Story of the Affair (May 1st, 1886 through November 11th, 1887)

Part II: The Spread of the Story (November 11th, 1887 through May 1st, 1989)

Representing the story of the Haymarket Affair is challenging because there is not one definitive telling of the story. There are thousands of pages of court documents available from the trial. There are books that have done additional research, recounting the events and hypothesizing about details. And then there’s somewhat of a mythical oral tradition distinct from everything recorded.

I do my best to capture a common version of the story and give context where aspects are disputed, occasionally in footnotes. I know many folks are already familiar with these events and their context, so you are welcome to skip to my conclusions and analyses. But if it’s been a while since you brushed up on the contours of this event, I’ll revisit the key dates connecting what some in the US still see as the most lethal anti-police act of violence of the 1800s to over 6.5 billion vacation days globally.

1871: The Historical Maylieu

a Confederation Consolidates, a Commune Collapses, a Cow Kicks a Candle3

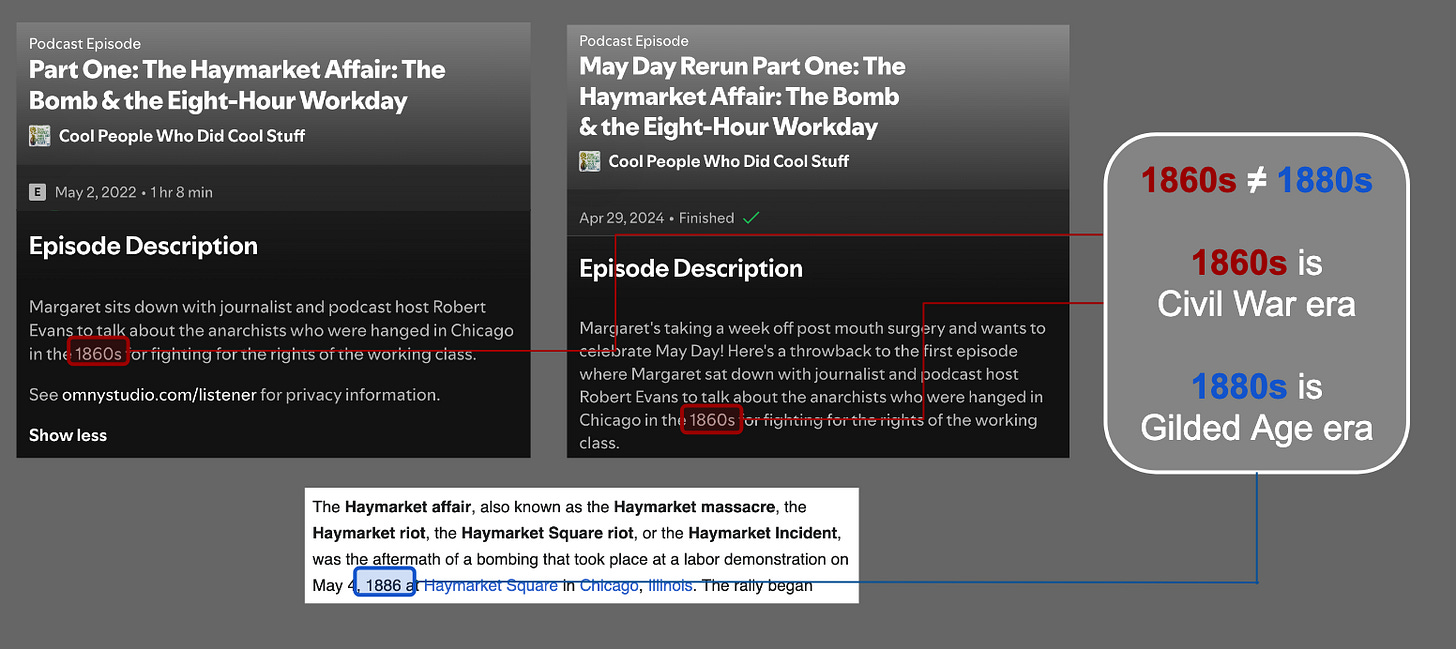

The 1880s, when the key events of this story take place, lacks a sense of specificity which can make the events hard to comprehend. For example, you could even be a history podcast so passionate about the Haymarket Affair that you make it the pilot episode of your series and still accidentally write that it took place in the 1860s.4

My point being: the 1880s are just a non-distinct old-timey time, and so giving some background will help process the story if it’s new to you.

Further, nearly all the secondary sources I consumed were told from a very American perspective, focusing on the more domestic mysteries of “who threw the bomb?” or “how did this impact the American labor movement?” But because the mystery I’m most interested in is the mystery of how this became such a global phenomenon, I think it’s helpful to view the story globally and begin, as most of the Haymarket defendants did, outside the country.

And if we’re going to allow ourselves some context for how the world saw the US in the 1880s, my advice would be to look to the year 1871. It’s a year that sets into motion both the forces that push our protagonists away from Europe and toward the United States. And the motivations it establishes help us see the entire arc of the narrative as an immigrant story.

So after the clock strikes midnight and “all acquaintance [of 1870] be forgot”, the world wakes to tidings of a pivotal year: European political upheaval and an American city’s global plea for support.

January 1st, 1871: The Empire/Reich’s Back

Having published and distributed a constitution on New Year’s Eve, the Northern German Confederation becomes a new German Confederation overnight -- expanding Prussian King Wilhelm’s militarist-authoritarian coalition further south and absorbing new states. This concludes a decades-long campaign of consolidation, earning elite support by crushing democratic uprisings in 1848 and expelling Austrian pluralists in the Austro-Prussian War. Wilhelm’s modern industrial state can at last reconstitute itself as the Second Empire or “Reich”, a nostalgic classification calling back to the 1007-year-lasting Holy Roman Empire.

The Prussians’ ability to operate a highly centralized system while savvily cloaking themselves in pseudo-democratic norms would bias those departing Germany against even seemingly well-meaning governance. This is part of what makes trust-building a challenge in the New World. For an example of this, you can look at their three-class franchise which is basically “what if the US Electoral College existed, but representing wealth instead of people”.

Most of the May Day Martyrs grew up in areas under increasing Prussian dominance and its accompanying rapid industrialization and rising authoritarianism. This political and cultural transformation not only drove them out of Germany but shaped their politics in the New World.

March 18th, 1871: The Communards Take Martyr Mountain

Meanwhile, in the Parisian working-class neighborhood of Montmartre, the civilian militia resists an attempt by the federal government to appropriate their cannons. Because the Prussian military had marched into Paris and forced the French military to disarm, the civilian militia alone is managing city security and is brimming with new recruits from artisan and manual labor classes. This gives them a numbers advantage that allows them to drive the military out of the city, putting Paris and its two million residents under complete local control.

For two months, the people of the Paris Commune experiment with self-governance. They held elections for a Commune Council with roughly half of all eligible voters participating. They created nine functional commissions to keep municipal services like railways and telegraph/mail delivery operational. They toppled the big statue of Napoleon as it was "a monument of barbarism". They decreed to bring back the old revolutionary calendar and its 10-day weeks.

After the military has time to regroup in Versailles, they return to take the city. It takes a week of violence, but the experiment is brought to an end and remains only an anecdote to be discussed and debated among historians.

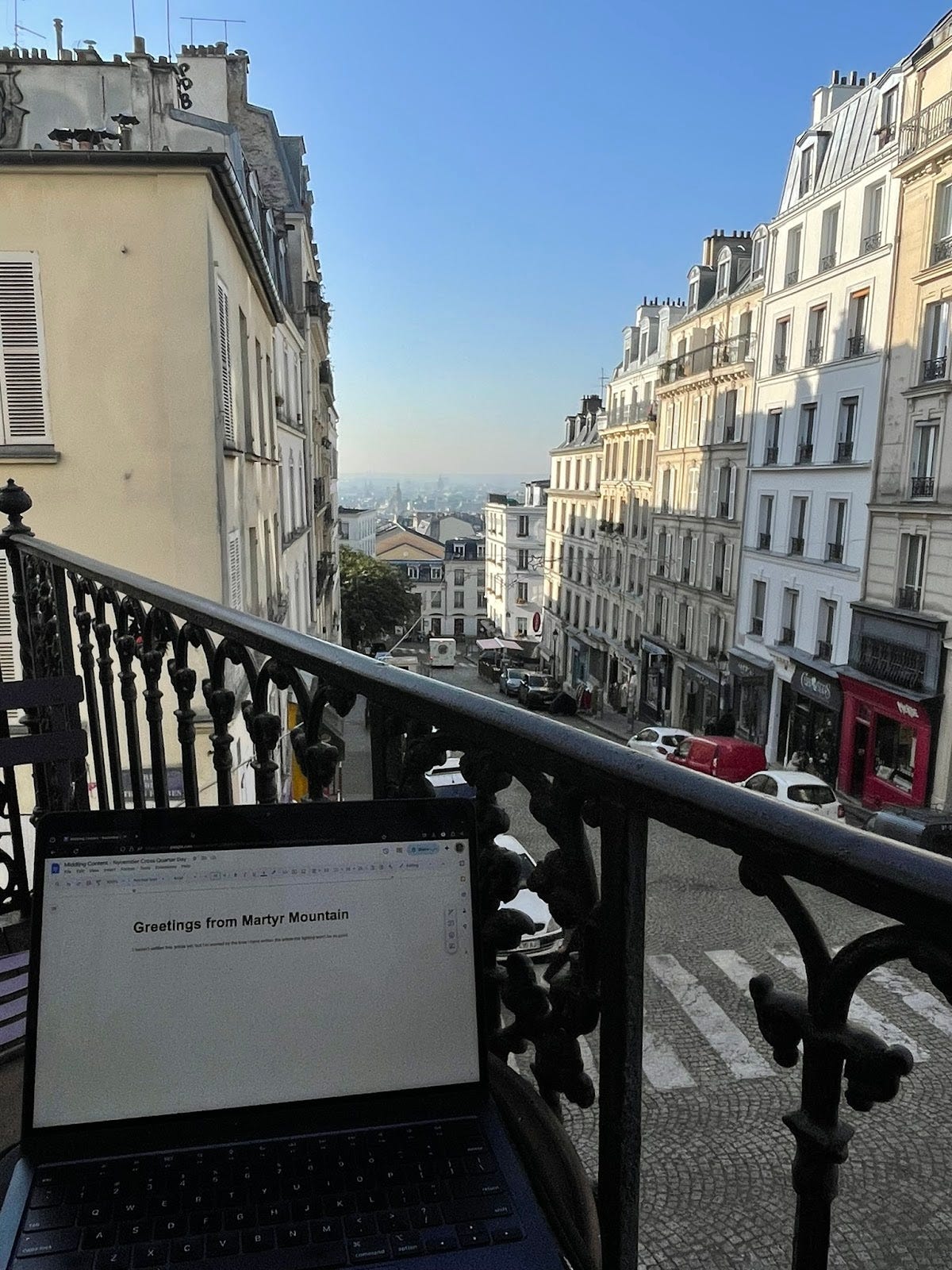

I stayed in Montmartre last October and hope to write about it in greater depth at some point. But for now there are really two important factors to draw from this:

In crushing the commune, France proves not-so-friendly to the cafe radicalism that some may have otherwise associated with it. Leaders were demonstrating further that they were willing to use state violence just as they had in the suppression of the Revolutions of 1848. This makes a transatlantic journey seem more compelling to those seeking a life outside of government oppression.

The other is that all other cities globally would be on higher alert, with the Paris Commune’s bloody conclusion elevating the term “communist” as a political epithet. It raised awareness of these radical political ideas outside of esoteric theoretical circles.

Oh if only some major city would just burn itself to the ground, creating a blank canvas for these European radical refugees and their utopian schemes…

October 8th, 1871: A Great American Fire

It is global news when a three-day fire burns through the city of Chicago, destroying over 17,000 buildings and leaving over a quarter of the city homeless. The city’s critical location between the largest estuary in the world and the largest river system in North America made it a natural logistics hub to take goods further west, so it would take the opportunity to rebuild and modernize to serve a growing country. The city would nearly double in population in the decade following the fire, and it is in this rapidly developing Chicago where the May Day mythology takes shape.

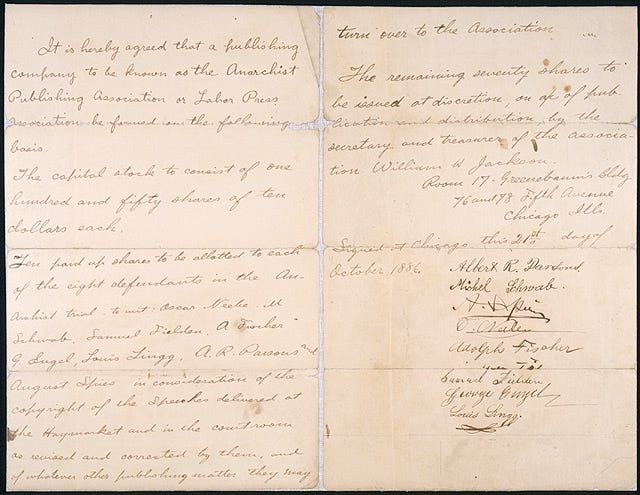

Of the Haymarket Eight, only one was in Chicago by 1871 and even he had just been there a couple years. Most were not even in the United States yet. They would eventually all become involved in the same broad movement, loosely aligning with International Working People’s Association and its anarchist Pittsburgh Manifesto with a few sharing office space for their publications, but their closest association as a large group would be as co-defendants in their 1886 conspiracy trial.

I’ve summarized what I took from their autobiographies and layered in some independent research of time and place, giving them each epithets because eight is a lot of names to keep straight. It’s worth noting that I’m not in a position to verify their claims, but there are two points to be forewarned as likely spurious.

First, my source for Louis Lingg’s childhood home address is an unsourced claim on German Wikipedia that I have not been able to verify elsewhere, though I provide some reasoning on its inclusion in footnotes.

And second, despite it being directly and plainly stated in his autobiography, I’m skeptical that August Spies was born in a castle.

With that, let’s start with August Spies.

1871: Before They Were Martyrs

The 🏰 “Castleborn” August Spies 🏰 [rhymes with “keys”] turns 17 in 1871 in Kassel, Germany, having grown. I put “castleborn” in quotes because though he claims to be born in the ruins of an old mountain-castle, I’m honestly skeptical of this. I walked up the mountain this castle is on, and the idea that his deeply pregnant mother made this hike in labor seems doubtful? Was she hiking to induce labor? In December? Adding to the suspicion is that the castle in question is cited on German Wikipedia as being built in the totally-not-made-up-on-the-spot year of 1234.

By the time he’s writing his autobiography, he seems very aware of how he’s fitting into history, so it seems fitting he’s crafting himself a hagiography. The story of the mountain castle allows him to pivot adeptly and elegantly into his pitch for socialism -- a pitch that winds through the curves of history. The rise and fall of serf lords, of religious systems, of empires give him faith a future despite the bleakness of his own end.

But childhood for the “Castleborn” Spies was largely positive. Having been educated by private tutors, he attends a prestigious Polytechnikum in Kassel that educated five early 19th century scientists notable enough to have Wikipedia pages and plans to be a government forester like his father. Unfortunately, after his father passes away he and his family are driven to make the move to America in 1872, and he eventually settles in Chicago where he is reported in 1880 in the US Census as an upholsterer. That same year he joins the staff of a workers newspaper, the Arbeiter-Zeitung, and he’ll be promoted to editor in 1884 which is the position he’ll hold during the Haymarket Affair.

The 💼 Journeyman Michael Schwab 💼 will eventually work with the “Castleborn” Spies as the Assistant Editor for the Arbeiter-Zeitung; he opens his autobiography pining about the Franconian forests which served as common property for him and his community growing up, and I imagine Schwab and Spies connected over their shared appreciation of forests.

In 18715, though, he is a 17-year-old apprenticing as a bookbinder in Würzberg, Germany. Having only recently arrived from his birthplace in Kitzinger, he completes his training and then his work search takes him to Bern, then Zürich, then Meerane, then Cologne, then Vienna, then Plauen. (And I am skipping over shorter stays in summarizing this.) It’s in Plauen working in a blank-book factory in 1879 that he decides to study English and try the United States.

He makes the trip to NYC, when he leaves for Chicago where he continues to study English and works a little in bookbinding. But Chicago doesn’t work out at first, and so he also tries Milwaukee, Kansas City, Denver and Cheyenne before returning to Chicago in late 1881. This time he’s more deeply networked in the social cause and finds work translating the book The Nihilist Princess for the “Castleborn” Spies at the Arbeiter-Zeitung. He is then offered a role as a reporter, and then promoted to Assistant Editor and Business Manager.

The third will-be employee of the AZ is 🍞 Understudy Oscar Neebe 🍞. Oscar Neebe is the only American-born of the German subset of the Haymarket defendants, though his parents' insisted he be educated in Germany, so like the “Castleborn” Spies he was educated in Kassel. By 1871, though, he was 21, living in NYC and manufacturing milk cans. In 1877, he’d return to Chicago, where he had spent some of his later teenage years earlier as a waiter.

In Chicago, he would find work at Adams' Westlake Manufacturing Company before being “discharged because [he] stood up for the right of working men”, after which he could not find other tradeswork, so he became a compressed yeast salesman and then started his own yeast business with his brother and some partners. He was on the publishing coop board that managed the AZ, and in that role he would step in when needed.

The 🤝 Liaison Adolph Fischer 🤝 is a 13-year-old in Bremen in 1871, a “free city” associated with the old league of merchant city-states. The city is perhaps most famous for a Grimm’s Fairytale about a quartet of farm animals that leaves their master to pursue a career as musicians in Bremen, an indicator of the sense of possibility a city like Bremen held at the time. The animals actually never make it to Bremen; instead they trick a group of robbers to give up their house instead. Kind of a “Babe meets Home Alone” vibe.

Liaison Fischer will move to the US in 1873 -- first to Little Rock where he is an apprentice compositor, then to Nashville, then to St. Louis and will make it to Chicago in 1883 with his wife and three children. In Chicago, he’ll serve as a typographer for “Castleborn” Spies’s Arbeiter-Zeitung while also co-editing a more radical publication Der Anarchist.

Liaison Fischer is important in the Haymarket trial because he is connected to both the Arbeiter-Zeitung and to “the North West Side Group” -- both are organizations connected with the anarchist IWPA, but whereas the the Arbeiter-Zeitung was simply a mouthpiece, the North West Side Group was focused on defense and direct-action.

It’s helpful to contextualize all this in the rise of private militancy in post-fire Chicago. Factory owners looking to ensure smooth productivity would hire their own security forces, and without much regulation and with Civil War veterans commonplace, it was pretty easy to find people to point guns at workers to keep them working. In response, laborers founded their own private militias, one of which was the “Lehr und Wehr Verein”. Wikipedia translates the name as the “Education and Defense Society”, but I think that misses the delight of how the name sounds. It says a lot about a militia that they commit to rhyming. “The Reflection & Protection Group”? “Maturity & Security Association”? “Skills & Kills Club”? I like to think they’re the kind of guys who would say “suns out, guns out”, but with actual rifles and muskets. The Lehr und Wehr Verein would be less active by the time of the Haymarket Affair, but the North West Side Group carried forward the principle that to balance power between owners and employees, the workers must be equally armed.

The next two defendants are not involved with journalism at all, but they were alleged to be at a “Monday Night Conspiracy” meeting connected with the North West Side Group of the IWPA.

The 🧸 Old Toymaker Georg Engel 🧸 is the only of the defendants that is already an adult in 1871. This is why I refer to him as old, not that his age is empirically such -- my take is that trees grow old and some maybe some species of sharks, but humans never do. But the Old Toymaker Georg Engel is the eldest of the group by over a decade, and so therefore I call him such.

On April 15th, 1871, the Old Toymaker Georg Engel turns 35 and he has already had a great deal of challenging life experience. Born in Kassel, he spent his earliest years in the same city where Understudy Neebe and “Castleborn” Spies attended private school. His experience there, though, would be much tougher. After losing his father at 18 months old, he would lose his widowed mother when he was 12. With no funds for schooling, he found a shoemaker who would apprentice him if only he had someone to pay for his washing and clothing, but alas had nobody.

He heard of others heading to the US, and realized this was likely his best path too. And so, for over 20 years, he will scrounge up what he can, constantly displaced by wars and economic distress, to make the voyage across the world to a country that will ultimately condemn him. At 14, he walked 100 miles from Kassel to Frankfurt, where after roaming the city starving he was eventually able to find someone to teach him the trade of painting in return for his labor. After training, he applied his skills in Mainz, Cologne and Düsseldorf until he arrived in Bremen in 1863, where he drilled with their militia to respond to a northern invasion from Denmark. (It’s worth noting that Liaison Fischer, from Denmark, would have also been in Bremen at this time, though he would have been just five years old.) He then made it to Leipzig but left to avoid the 1866 Austro-Prussian war. In 1868, he moves to Rehna, is married and starts his own business, but rapid industrialization and the factory system forces him to close down.

It is in 1873 that he finally makes it to the United States with his wife and young children. He spends a year in Philadelphia and though he initially finds some decent paying work at a sugar refinery, he quickly becomes ill and his family is starving. He moves to Chicago in 1874. As his life stabilized, he found more opportunities to read and become politically engaged, first becoming involved with the International Workingmen’s Association until it was disbanded in 1876, then helping to organize the founding of the Socialistic Labor Party of North America which would successfully elect four Chicago alderman, three Illinois House Representatives and one Illinois State Senator. In 1883, he would become an active member of the IWPA and its militarist North West Side Group.

He started his toy store with his wife in 1876 and she continued to run it after he was imprisoned.

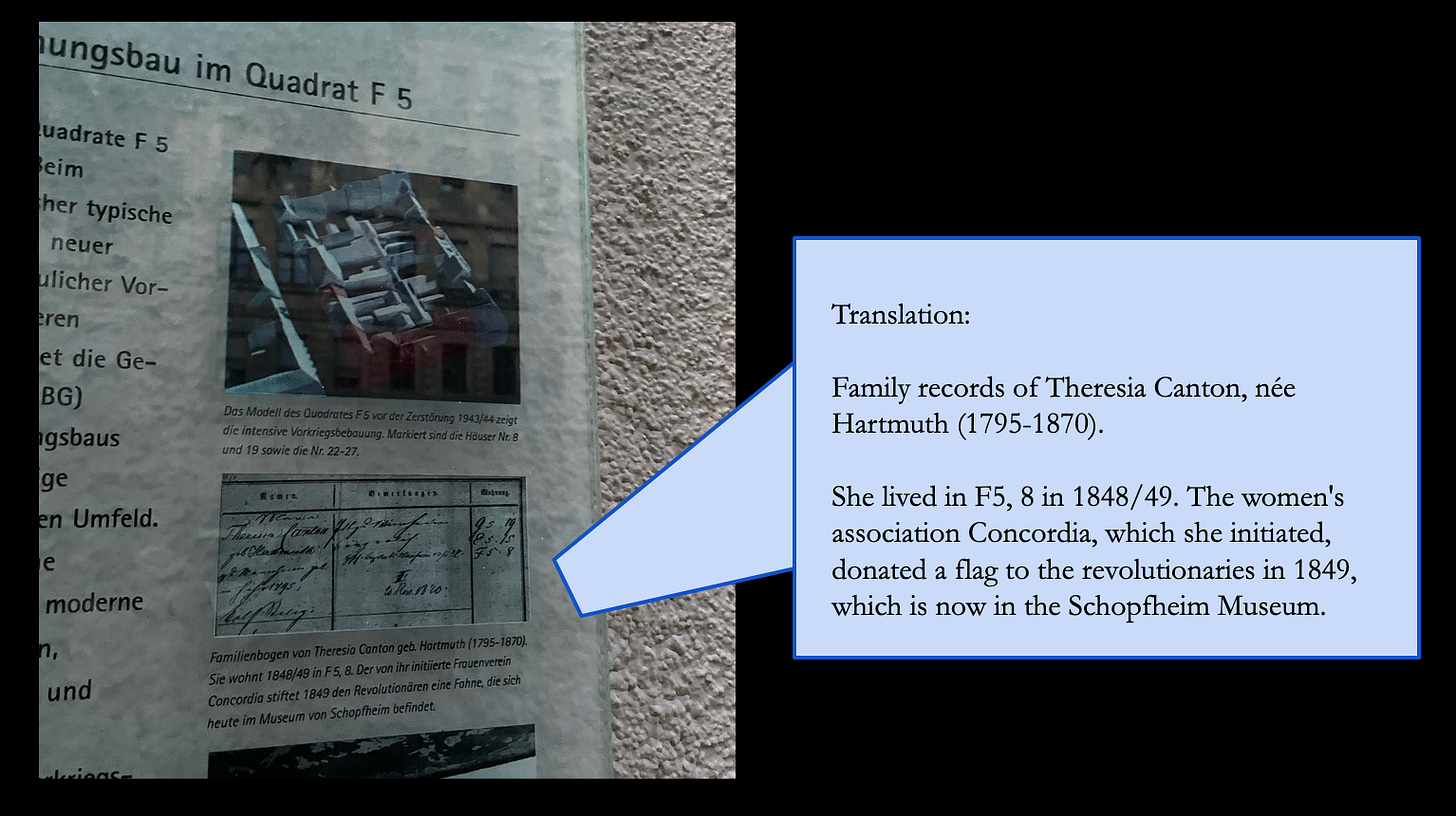

At the start of 1871, 💣 Young Bombsmith Louis Lingg 💣 is only seven years old. He lives in the “Mannheimer Quadratestadt”, a unique number-letter planned grid system that as far as I can tell exists only in Mannheim. Instead of a street and a house number, each home would have a square with its North-South position dictated by a letter, its East-West position dictated by number, and then radial positioning by another number. See how easy it is?6 It’s the sort of radical design thinking that befits an engineering city that claims to have birthed the invention of the bicycle, the car and the plane. The Young Lingg would eventually be an engineer as well -- specifically, a bombmaker.

Even within the radically designed SquareCity, the Young Bombsmith grew up on a block with particularly radical history: Quadrat F57. This block housed the print shop that printed the Mannheim Evening Times, a radical democratic newspaper that would publish the Mannheim Petition of February 27th, a call for a bill of rights that spread revolutionary fervor across the country and sparked action across the country. This published call to revolution was the first of a wave of such calls in Germany and resulted in the imprisonment of the newspaper’s editor, Peter Grohe.

The specific rights in this call for a bill of rights were a major influence on both the formation and legislating of the Frankfurt National Assembly, Germany’s first freely elected parliament of all German states that was elected two months later on May 1st. (38 years before our May 1st.) They passed the Basic Rights of the German People reflecting the Mannheim Demands in December, and then the following March passed a German Constitution. When they offered the role of Emperor to the Prussian King, he declined the offer to rule a democracy, saying he “will not pick up a crown from the gutter”; as discussed before, Wilhelm and Bismarck would instead create their own unified Germany with “blood and iron” in 1871.

And so, in 1849, the Prussian state mobilized their military to crush the uprising in Mannheim. The 48ers fought for their democratic constitution while the monarchy forces occupied the city just south of Mannheim. Lingg’s radical F5 block was also home of Maria Theresia Canton, who founded the Concordia Women’s Society, a pro-democratic organization that supported the freedom fighters, and is documented gifting a legion from Poland a flag -- presumably the flag of the Frankfurt National Assembly government, which flew the same German tri-color design still used today. This would be deemed incitement, and after the Prussians crushed the uprising they banned the Concordia organization and denied Canton her pension.

And to speculate broadly: the freedom fighters defending Mannheim were being led by Ludwik Mierosławski, and so it’s at least a possibility that Louis Lingg, who was born “Ludwig Link”, was even named after the man who defended the city. It’s also true, though, that the occupied city south of Mannheim is called Ludwigshafen, named for the anti-revolution King Ludwig I. So, you know, I guess lots of people seem to be called Ludwig8.

Moving forward again to 1871, Young Louis was too young to experience the revolutions before his time, but the influence of this community was likely still felt. And further, many 48ers left Germany after the democracy movement failed and instead moved to the United States to fight for the Union Army, so it is unsurprising that he saw about United States as a place of freedom but I expect he grew up hearing old stories of evil reactionary rulers and the men chasing revolutionary dreams. I don’t see how such an environment wouldn’t cultivate a love of freedom.

If the political history of his neighborhood was not enough, the Young Lingg’s childhood alone will be sufficiently radicalizing. As a thirteen-year-old in fast industrializing Mannheim, Germany, he saw his father incapacitated by a lumber mill accident, made a victim by his own hustle. The accident broke his father’s spirit, which in turn resulted in him losing his job. For the next three years, the Young Lingg would watch his father die slowly. Determined to maintain control of his own life and career, Lingg trained as a carpenter, as a tradesman could have more agency than a day laborer. From ages 18 to 21 he set out into Germany and Switzerland, finding work and joining worker’s organizations. At 21, to avoid mandatory military service and with money secured by his mother from her new husband, he travelled to NYC and then Chicago to build a new life in the new world.

And the final two I group together as “Anglo Allies”. Whereas the IWPA is primarily a German-American association in Chicago, these two are drawn in despite not sharing that ancestry.

Only one of the Haymarket Eight was already in Chicago in 1871, and that man was ⛪ Lay Preacher Samuel Fielden ⛪. He was relatively new there, having left his family home in Lancashire, England only a couple years prior. Then 21-years-old, he headed to New York City where he briefly worked at a Brooklyn hat factory before packing cloth at a textile mill in Providence and working at a farm outside of Cleveland. Once in Chicago, he was a laborer on public projects like the Illinois and Michigan Canal and Douglass Park. The day of the fire, he was working on the drainage of Mud Lake near where today the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal runs north of Midway Airport. After about a decade of working for others in 1880, he used his savings to buy a team of horses and operated his own business hauling stone.

It’s around this time that two paths of his begin to merge. He had been religious in his upbringing, joining the Methodist church at 18, following in the footsteps of his mother who had passed back when he was 10. His involvement grew, and he was even “on trial” to serve as a local preacher but plans were interrupted and he chose to head to America. He continued with preaching while doing farmwork in Ohio, but in Chicago after a late night debate with D. L. Moody (of Moody Bible Institute fame) felt further from the church and instead found a use of his voice in the world of labor agitation.

He was involved with the creation of a Chicago Teamsters Union of which he was elected Vice President, though the union did not end up being effective and disbanded. He joined the Chicago chapter of the National Liberal League which advocated for separating church and state, and as an officer he represented them at a national convention. Most crucially to our purposes, he became a member of the IWPA and was a frequent speaker at their events, which is how he ended up speaking at Haymarket Square on May 4th, 1886 at the moment when the bomb was thrown.

Finally, we have 🇺🇲 American Idealist Albert Parsons 🇺🇲. In 1871 he was working in Austin, TX with the Texas state government, helping fill vacancies created by reconstruction era bans on ex-Confederate officials. In addition to his election as a secretary to the state senate, he also held one of the least anarchist jobs conceivable: an IRS tax collector.

Indeed, Parsons' resume is all over the place. Born 1848 in Montgomery, Alabama, he’d lose his mother at 2 and his father at 5 and be sent to Waco, TX to live with his sister. With a family with centuries of American heritage and several officers who fought in the American Revolution, it perhaps unsurprising that as a 13-year-old he snuck away to join his local military company -- though this being 1861 that meant he was on the side of the Confederates in what he would later call “The Slaveholder’s Rebellion”. After the war, he’d trade a mule for some corn for six months of college that prepared him to launch his own newspaper, the Waco Spectator; in his journalism and later in direct political action, he supported the rights of newly enfranchised Texans.

He would come to Chicago at 26 years old with his wife Lucy Parsons, getting a job as a typesetter for the Chicago Tribune. Investigating the accounts and activities of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society made him sympathetic to the worker’s plight, driving him to ultimately join the Social Labor Party of America and Knights of Labor. As a candidate with the Workingmen’s Party of the United States he would run for alderman three times, county clerk twice and US congress once; the Workingmen’s Party nominated him to be their presidential candidate, but he had to decline as at 31 he was too young to qualify. A speech to tens of thousands of striking workers during the 1877 Great Railroad Strike led to threats on his life, his firing from the Chicago Tribune and a general disillusionment with electoral politics.

In 1883, the American Idealist Albert Parsons will attend the Pittsburgh convention where the International Working People’s Association is founded, and it is in association with this group that he launches his anarchist weekly The Alarm. With this publication as his platform, he advocates for the eight-hour work day within a political frame of anarchism. He publishes from the same building as fellow IWPA publication the Arbeiter-Zeitung at 41 N. Wells St.

Viewed out of sequence, Parsons' politics seem almost chaotic; like a petitioner’s dream passerby, he seemed to join anything. But his arc is clear: a confederate at 13, to a Republican at 18, to a socialist at 26, to an anarchist at 32.

And he will be 37 when he and his family lead that first May Day Parade.

Okay, I think you’re caught up. Let’s dig in.

Part I: The Story of The Affair

May 1st, 1886: The Parade

On May Day, Parsons and his wife and his two young children marched in support of Eight-Hour Workday on a day that had been selected years in advance to enact a general strike.

This is of course the day commemorated as Labor Day in much of the world; its power is less in narrative nuance than in the sheer mass of people participating in a general strike for an eight-hour workday -- as many as half a million Americans by some estimates. Chicago, the center of the movement, sees 30k-40k striking and as many as 80k marching down Michigan Avenue. It’s a strong foundation for the lore that events to come will build upon.

This year, there were marches in Chicago again; to give a sense for relative scale, Block Club Chicago estimated the participant number as “thousands”, so the march of 1886 could easily have been ten times the size.

I spent the day working on an early draft of this blog post instead of attending the march (boo me!9), but I did attend the Haymarket Memorial Plaque Dedication, which occurs every year at the old Haymarket Square site since the current honorary installation was put up in 2004.

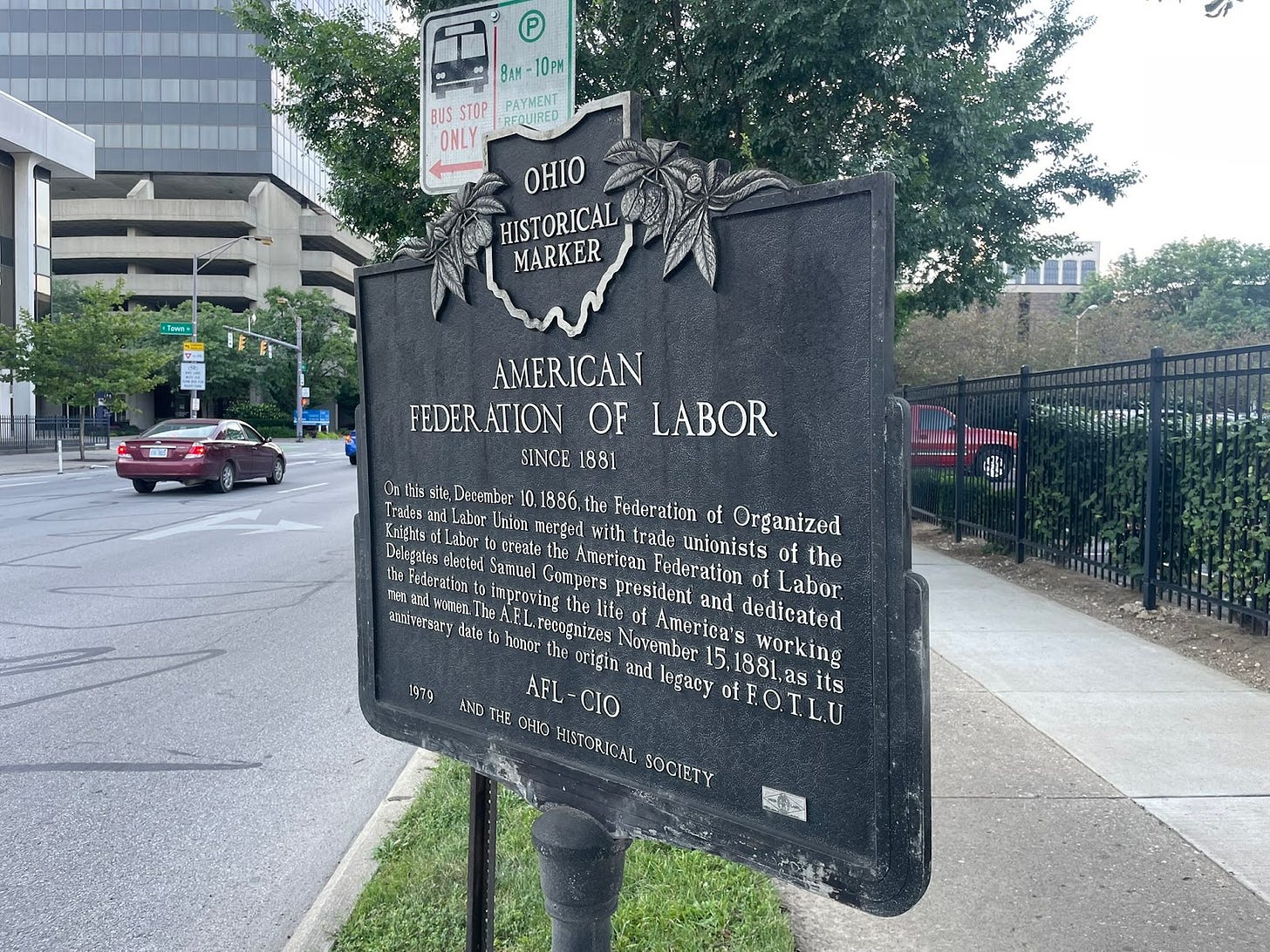

This year the plaque was from the Illinois AFL-CIO. Neither the AFL nor the CIO existed on May 1st, 1886, but the AFL would be founded later that year in December. I happened to learn the founding date of the AFL because I stayed in a Holiday Inn in Columbus, OH in June that happened to be on the grounds where the AFL was founded, with a plaque up as to mark the space.

Placing an AFL plaque on the Haymarket Memorial is a particularly interesting choice because it will be an AFL founding officer, Peter J. McGuire, who is credited with being the “father of Labor Day” as a September celebration. They say he proposed the idea in 1882 to the New York Central Labor Union.

The AFL-CIO website also calls McGuire the “founder of May Day”, as while serving as a delegate representing the United Brotherhood of Carpenters, he proposed that the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (a precursor to the AFL) directly enforce the eight-hour workday on May 1st, 1886. It is perhaps one of many examples where the invention is less consequential than the marketing; I’d say that McGuire is perhaps the Zune to Parsons’ iPod. An AFL marker on an IWPA memorial truly does embody solidarity forever.

What catches the world’s attention, though, is where things go from here.

May 3rd, 1886: The Escalation

After their Sunday day of rest, many workers are ready to carry out their general strike.

At the McCormick Reaper Works, strikers led by the “Castleborn” August Spies confront workers and when police become involved guns are fired and two workers10 are killed. Outraged at the killing, strikers use the printing presses of August Spies’s Arbeiter-Zeitung calling for a gathering to protest police violence.

I could not find any buildings from the McCormick Reaper Works still standing, but it was an absolutely massive plant in its time. From what I read, it seemed reminiscent of the massive factories we now associate with Chinese manufacturing. I believe some of it existed on the banks of the river across from the Daley Park Boat launch, which I visited on May 3rd.

It seems a bit unfair to me that this series of events is referred to as “The Haymarket Affair”, when the initiating events take place the day before the Haymarket gathering; by centering the story on the May 4th events instead of the May 3rd shooting, we lose the Monday context for the tension that likely sets Tuesday’s tragedy in motion.

After all, it is at the McCormick Reaper Works, not at Haymarket Square, where the first blood is drawn. And this was a repeat offense, with workers11 killed by McCormick’s private security forces during a strike the prior year, with no consequences faced by the Pinkerton guards responsible. Does it not make sense to instead call this whole episode “The McCormick Affair”? Or does that clash too strongly with McCormick Bridgehouse, McCormick Tribune Plaza and McCormick Place?

I do speculate that the McCormick Reaper Works is honored in historical iconography, regardless of how Americans refer to the series of events in their own history books. What symbol might you select to counter the mechanized farming technology McCormick develops? An old-fashioned reaping device of some sort? Though it’s merely conjecture, the “sickle” in the classic communist “hammer and sickle” could be seen as a historical allusion to the McCormick’s place in sparking a labor revolution.

Regardless, it is in response to this series of worker killings that the motivates the “Monday Night Conspiracy” meeting later this night, with Toymaker Engel and Liaison Fischer allegedly deciding that a designated codeword “ruhe” (German for “quiet”) will be published in the Arbeiter-Zeitung, signalling to the broader labor militia groups that they should take arms -- the revolution is nigh.

May 4th, 1886: The Assembly

Thousands see the flyers printed by the Arbeiter-Zeitung, and as many as 3,000 gather in Haymarket Square to protest the killings. That evening, the “Castleborn” Spies, the Idealist Parsons and the Preacher Fielden deliver speeches to a crowd that the mayor would later testify was peaceful.

Around 10:30pm, police ask the crowd to disperse. The Preacher Fielden is just completing his remarks, and when the police ask the crowd to peaceably disperse, Fielden reinforces their message, saying “but we are peaceable”. Perhaps hearing “peaceable” as a reference to the call-to-revolution codeword “ruhe”, someone launches a homemade bomb into the air, and when it lands near a police officer, Mathias J. Degan, he is killed. The resulting gunfire and chaos lasts a brief five minutes, killing six more policemen and at least four workers. Many more are injured, including Preacher Fielden who is shot in the leg. The crowd quickly scatters to escape the violence.

Over the next few days, the police seek out those they see involved with the conspiracy. August Spies and Samuel Fielden are arrested for their speeches which are seen as riling up the crowd. Albert Parsons is sought out for his speech as well, but he has fled the state. Three employees of August Spies at the Arbeiter-Zeitung are also arrested (Michael Schwab, Oscar Neebe and Adolph Fischer) for their connection to the flyers that drew together the crowd. Louis Lingg is arrested when his landlord reports him for assembling bombs in his apartment. George Engel is arrested for his attendance at a planning meeting for the event.

The detective’s lead suspect to have thrown the bomb is Rudolph Schnaubelt. He is captured by police, interviewed and then let go; after his release, he crosses the border to Canada, then escapes further to England and then to Argentina.

June 20th, 1886: The Homecoming

The police tell Albert Parsons’ wife, Lucy Parsons, that his evading capture in hiding gives credence to the conspiracy case. The four employees of the Arbeiter-Zeitung share an office with his own publication, The Alarm. To show solidarity with the fellow defendants and to demonstrate both his and their innocence, he realizes he must return and stand trial.

On the night of his 38th birthday, Parsons leaves Waukesha, Wisconsin and travels through the night back to Chicago. He reports to a police station and turns himself in. It is the Summer Solstice, and the days get shorter -- for everyone, and especially for Parsons.

June 21st, 1886: The Trial

The trial opens the same day Parsons turns himself in, and jury selection begins.

There are thousands of pages of testimony and evidence online in the Haymarket Affair Digital Collection provided by the Chicago Historical Society. The trial runs roughly seven weeks, from June 21st through August 11th. The jury deliberates for only a few hours. Their verdict, delivered August 19th, is that all eight men are guilty. Seven12 are condemned to death.

On October 1st, the Haymarket defendants’ counsel motions for a retrial, naming 14 justifications and providing new sworn testimony that contradicts existing testimony. The concerns include how the jury was constructed13 with deliberate bias, how the instructions to the jury were inconsistent with the law, how the judge didn’t permit dividing the trial to handle the militant IWPA North West Side Group separate from those merely involved in writing and speaking, and how the “verdict is manifestly illegal, unjust and against the testimony”. On October 7th, though, the motion is overruled.

The executions are planned for December 3rd. Roughly a week before, on Thanksgiving Day, they are granted a “writ of error” from the Illinois Supreme Court -- putting the executions on pause and setting a date for their appeal on March 1st in the new year. Closing arguments are held on March 18th, but the court’s 220-page decision isn’t published until September 14th of that year, when it affirms the original conviction. A new execution date is set for November 11th.

Nov 10th, 1887: The Lineup Changes

An attempt to appeal to the US Supreme Court is unsuccessful, but the Governor of Illinois is conflicted by the case. A “Radical Republican” and former major general in the Union Army, he is no stranger to passionate and violent pursuits of noble ideals. And so, to those who ask for clemency, he will reduce the sentence to “merely” a life of hard labor in prison. Of the seven on death row, two take the deal: Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab. Less than 24 hours before their scheduled execution, they no longer face the noose.

Five remain on death row, with Louis Lingg the only of them with a clear connection to the violence in that he potentially assembled the bomb. As you recall, at 21 he was sent to the US by his mother to pursue his dream of moving to America. Now 23, Lingg has now spent the majority of his new-world-new-life held captive within the Cook County Courthouse and Jail. He was only in Chicago seven months before his apprehension by police, and he’s been awaiting his fate for over twice that time.

If Louis Lingg were to hang for associations with the bombing, then the county could at least know they were punishing one man with plausible direct connections to the violence. The trials did show bombs allegedly from Lingg’s apartment that were similar to the one used on that prior May 4th. While I’m not certain about his participation, and many claim the innocence of all seven martyrs, having a bombmaker among those persecuted would at least provide better optics to the state in their performed justice.

Alas, the night before executions would be carried out, Louis Lingg places a blasting cap between his lips like a cigar. He then, lighting it, blows up his own face. While he slowly dies over the next six hours, he scrawls “Hoch die Anarchie” (“up with anarchy”) on the jail cell floor in his own blood.

This leaves only four non-violent men scheduled to hang the next day: three journalists and a toymaker.

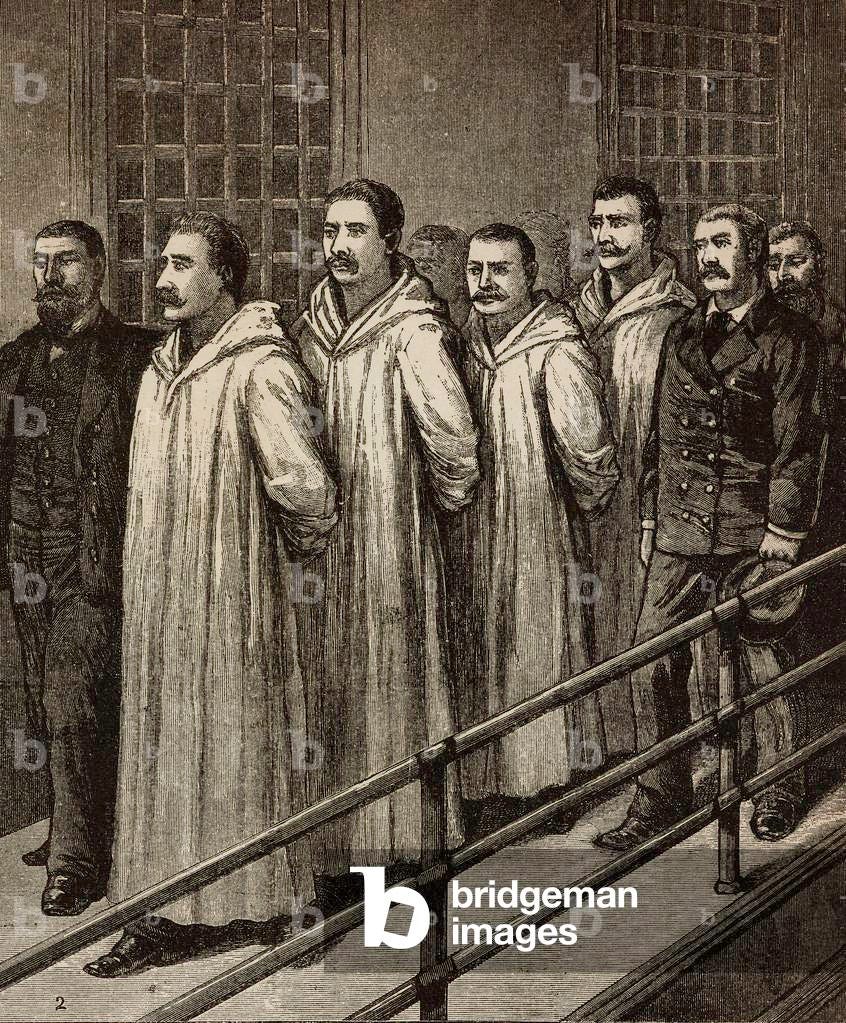

Nov 11th, 1887: The Martyrdom

Dressed in white robes, the four activists marched to the gallows by the Cook County Courthouse singing the Marseillaise. In the moments before their death, August Spies shared his last words, “There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today”. Adolph Fischer and Georg Engel shout “Hoch die Anarchie”, echoing the Young Lingg’s bloody scrawl.

I have often been dismissive of the term “leftist”, as asking “where would this person sit in the 18th century French parliament” has the same vibe of describing a foreign city’s neighborhoods with NYC boroughs. But something about these martyrs walking to their death singing the “Marseillaise” has me thinking differently about this. Something about the German-born Americans singing a French swan song captures the transatlantic identification with the revolutionary story that grows into the global labor movement.

On the anniversary of the Haymarket Bombing this year, I ate ramen across the street from the former Cook County Courthouse where the Toymaker Engel, the Liaison Fischer, the “Castleborn” Spies and the Idealist Parsons were executed. I was listening to an audiobook (finally getting around to Cobalt Red) but it wasn’t loud enough to drown out being bookended by two Hinge dates who seemed much less interested in the historic hangings that had taken place outside ~138 years ago.

While we do not get May Day off in the US, it’s somewhat ironic that the US does provide a Federal Holiday on November 11th, which is the anniversary of the martyrdom. What we now call Veterans’ Day was once called Armistice Day, honoring the day in 1918 when the people of the world decided to stop killing each other for a while. While many of the fighters were young men who weren’t yet born, anyone over 31 would have been alive when an American and three Germans died side-by-side for a loosely shared idea of freedom. And if you think of Veterans’ Day as a day where we celebrate those who risk their lives to protect their vision of the American Dream, perhaps there is room in your conceptualization to reflect on the May Day Martyrs.

After the four had died, a funeral procession was held where participants wore red ribbons and sang the Marseillaise. The more modern anthem “L’Internationale” was not yet composed, and would not be used ceremonially until the Second Internationale would assemble in 1889.

It would be at this meeting that the global journey of the Haymarket mythology begins.

Part II: The Spread of the Story

The world was watching as the executions provided a definitive conclusion to the Haymarket Affair, but the struggle that the May Day martyrs were fighting for was far from over.

July 14th, 1889: The Holiday

Over three years later, a gathering would take place in Paris on the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The goal was to reorganize workers in the continued struggle for workers’ freedoms.

That gathering, “The International Workers’ Congress”14, would result in the formation of the “Second International”. The “First International” was the International Workingmen’s Association15; the “International Working People’s Association” was also called the “Black International” but it does not receive a number, only a color. (We honestly need an equivalent of those monarchy lineage charts but for all these labor organizations.)

Whereas the First International began its collapse when it kicked out the anarchists 8 years into its founding, the Second International was a new start and re-engaged with the anarchists in fellowship until kicking them out again 7 years later. (It’s important to recognize this was an earlier era when the Left struggled to hold together a broad coalition and would constantly become mired in counterproductive infighting.)

The constituency of The International Workers’ Congress was so divided, the people who had gathered for it were literally split into two separate factional meetings: The Marxists meeting at the Hall of Parisian Fantasies (“Salle des Fantaisies-Parisiennes” at 42 Rue Rochechouart) and the Possibilists meeting a 25-minute walk to the southwest at the Union for Trade and Industry (10 Rue de Lancry). It would be in the Hall of Parisian Fantasies and on the final afternoon of the congress where the motion to create a global May Day would be put forward and passed.

The holiday was first simply a decision to demonstrate on the 1890 anniversary of the original Chicago demonstration. The AFL in the US had already set this date, and the Second Internationale was presenting a broad global coalition of support. After initial success, it became recognized as an annual event the following year.

June 26th, 1893: The Pardon

Though 1893 had a particularly noteworthy May Day, with President Grover Cleveland giving his opening address at the World’s Columbian Exposition, the more remarkable date would be a couple months later when Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld would drop a 16,545-word pardon16 for the three imprisoned of the original Haymarket Eight. This was deeply controversial and even earned Altgeld a place in Profiles in Courage (the TV show, not the book).

One note here though: Altgeld calls the circulation of the IWPA-affiliated publications small, which is kind of sad for the state to do as a part of the pardon; he basically calls their life’s work of writing inconsequential? If I am ever murdered by the state for anything I write in this Substack, please don’t posthumously pardon me by saying that nobody even reads my Substack. I am aware that just a few friends of mine read my Substack to humor me, but that just feels unnecessarily hurtful.

Altgeld is remembered by a plaque in his birthtown of Selters that faces a skatepark.

Though Altgeld’s publication of his reasoning is titled “Reasons for Pardoning Fielden, Neebe and Schwab”, it is later republished under broader headers, such as a pamphlet published by Lucy Parsons titled “Gov. John P. Altgeld’s Pardon of the Anarchists and His Masterly Review of the Haymarket Riot”. This later titling encourages a broader reading of the Altgeld pardon. Though he does not explicitly pardon the four men killed in 1887, his reason mostly focuses on discrediting the process as a whole -- including selection of jury, competence of jurors, fittingness of the charge and overall judge bias. This strengthens the martyrdom narrative and builds into the myth.

June 28th, 1894: The Other Holiday

The following year, President Grover Cleveland is back in DC and signs S-730 (“A Bill Making Labor Day A Legal Holiday”) into law.17 The bill had been proposed almost a full year earlier by North Dakota Senator James H. Kyle from the Populist Party, but now the country is deep in a summer-long strike and boycott of the Pullman Company and the government is looking to show solidarity with working people. Many states already recognize the first Monday of September as Labor Day, and this broadens the reach of the holiday.

As mentioned earlier, the September Labor Day was first celebrated in New York City in 1882 -- nearly four years before the May Day March that would escalate and capture the world’s attention. As for who to credit for the 1882 parade, historians dispute between two similarly surnamed strikeleaders, Peter McGuire18 and Matthew Maguire. It’s a topic for another essay.

I didn’t focus on the September Labor Day so much in my research, but I did enjoy how congressional candidate Kat Abughazaleh tied the two together in her history explainer that covers the Pullman Strike in greater detail.

October 24th, 1938: The Workday

It’ll be on the other side of World War I before the US passes a broad eight-hour workday in The Fair Labor Standards Act. As one of the key components of New Deal legislation, it is signed into law by FDR on June 25th, 1938 and then takes effect on October 24th, 1938.

The bill is famous for guaranteeing time-and-a-half wages for time worked over forty hours, establishing the norm of a five-day workweek of eight-hour workdays. (The original 1932 draft from Alabama Senator Hugo Black actually set the workweek at 30 hours, which perhaps was merely shrewd negotiation.) In addition to encouraging limits on working hours, the bill also decrees a federal minimum wage and prohibits child labor. Bangers all.

It took over fifty years from the original May Day march, but at last the dream of the eight-hour day has been achieved.

December 21st, 1939: The Flag

And now let’s engage in baseless speculation.

When Chicago’s May Day March movement had finally achieved its mission, restricting work hours and protecting free time and free thinking, there were only three stars on the Chicago Flag.

Initially adopted in 1917, the Chicago flag had featured two stars for events already discussed: the Great Chicago Fire and the World’s Columbian Exposition. Chicago then adds a star to the flag as a promotional stunt19 for the WCE’s sequel in 1933.

And so here we are in 1939. Chicago’s historic and globally renowned labor movement has achieved a critical policy goal that liberates laborers across the country. The march and movement that captured the hearts and minds of people, though never finished, can finally call itself a success. Chicago City Council gathers. They have a new star in mind. Along with the fire that drew support from around the world and two world-famous fairs that drew global crowds, the Chicago Flag will add a star for… Fort Dearborn?20

I’m not going to talk about Fort Dearborn at all. I did read some about it. Someone wanted to name a bridge after Fort Dearborn and then the City Council was like “no let’s add a star to the flag instead”. And so they did.

It does lend itself to a conspiracy theory though: what if the “fort” is actually code for the “fort-y hour workweek”? Hmm? And the radical Chicago City Council of 1939 just knew that celebrating leftwing activism of the late 1800s would be too much for most people to swallow? So they had to do that thing that kids do on TikTok where they use “unalive” instead of “kill” to evade automated content moderation. It is perhaps a little open to interpretation.

I’m generally opposed to government speech regulations, but it does feel like there should be some regulation as to what can represent a star on a flag. When someone dreams of becoming a movie star, they are dreaming of becoming globally recognized -- a star is seen in the sky regardless of your provincial habitation. When Chicago burned down, drew donations from 2521 foreign countries making it a global affair. The World’s Columbian Exposition has at least 3422 countries represented and the followup Century of Progress has at least 1823 countries represented -- not including attendees which would span even wider. The May Day March not only set into motion nationwide policy achievements but it would become a holiday in 180 countries, making it more recognized than Christmas. What has Fort Dearborn done? Does anyone outside of Chicago know about it? I’m skeptical.

Those in Chicago can claim the stars mean whatever they want. Seen from abroad, though, I like to think the stars represent Spies, Fischer, Engel & Parsons. Four men whose origins were outside of Chicago, and whose legacy burns brightest outside the city and country where they made history. One needn’t obsess over the particular minutes of the Chicago City Council. We can disregard “alderial intent” and all that post-modern literary theory stuff.

May 1st, 1955: The Canonization

As May Day ages into its 60s, it starts to get religious.

The Catholic Church, in part attempting to deepen its solidarity with the working Catholics of the Soviet Union, gets in on the May Day hubbub. Pope Pius XII adds a second feast day for St. Joseph, supplementing March 19th. Saints Philip & James, who already have the awkward situation of sharing a Feast Day, must now also oblige as the church asks them to move their feast day a couple days later to May 3rd to accommodate the new holiday.

St. Joseph was a carpenter, just like the Bombsmith Louis Lingg and AFL President Peter McGuire. And so St. Joseph gets a feast day of St. Joseph the Worker on the same day as May Day / International Workers’ Day.24

May 1st, 1958: The Other Other Holiday

As May Day has grown globally, along with the central myth of the Haymarket Eight, the US feels it must counterprogram. The Eisenhower administration creates an American alternative to the seditious socialism of May Day: “Law Day”.

I like to think the parallel six-letter length was to trick communists into revealing themselves in a crossword puzzle clue “holiday that starts the fifth month”. It is evenly weighted in length to remind you that it is just as real a holiday as May Day is even though you maybe never had heard of it until just now.

Eisenhower rang in the first Law Day, reminding us: "In a very real sense, the world no longer has a choice between force and law. If civilization is to survive, it must choose the rule of law."

If the purpose of the day is about rejecting force, then I think the freedoms fought for in the May Day movement are broadly aligned.

May 1st, 1989: The Stadium

It is the year following the 1988 Seoul Olympics, and Pyongyang wants to show it too is a part of the global community. It, like the government in Seoul, celebrates May Day on the first of May. And it, like the Olympics-hosting city of Seoul, can build a big stadium. Bigger even than the stadiums that held Olympic athletes from all around the world! It is at the time the biggest stadium in Asia and would eventually be the biggest stadium in the world after Prague decommissions its giant gymnastic center.

Though they are politically isolated, the hermit kingdom wants the world to know that they are not so different maybe. They celebrate May 1st like just about everyone else. They like to gather around in a circle by the tens of thousands and cheer for/against teams and contenders. And they are around if you’re looking for an enormous sporting hall for a transnational athletic competition of some kind.

How To Go Viral in the Late 1800s

One of my first jobs out of college was working in Hollywood as a data analyst that helped major US broadcast networks like CBS, ABC and FOX decide what TV pilots to put on the air; I designed and developed a dashboard that was used to determine programming that over a hundred million people ended up watching. For better or for worse, it’s probably the most impactful dashboard I’ve ever made.25

Every day while eating my lunch I would listen to longform podcast interviews with writers talking about their processes and frameworks, so I’ve easily listened to over a thousand hours of interviews with TV writers. I hoped that one day maybe I would be more involved in creative details, but my career took off in the direction of researching new ad platforms. (There is always a sense of gravity toward “where the money is”, and there was a lot of money in then-tween-age Silicon Valley social media companies; on top of that, the network creatives generally wanted research folks to stay in their lane.) Still, I layer in these elements and frameworks to hopefully approach Story in a way that is not excessively clinical.

In TV pilot testing, the most important measure for deciding what shows got picked up was self-reported intent to view more episodes. We’d recruit people all over the United States to sit and watch the first episode of a TV show (“the pilot”). When we wanted to break down a pilot that wasn’t working, the diagnostics focused on three measures: characters, concept and execution. Ultimately, I see the May Day Myth as succeeding on all three core elements.

1.) The Characters: 3 Stolen Rules to Engineer Love

In the old days of television, researchers would highlight the importance of characters by emphasizing that by tuning into a program a viewer was inviting the characters into their home. We can think of modern programming whose casting seems to appeal more to our sense of curiosity, but while shock or strangeness can help initially draw attention, the longevity of a story relies on building a story world that people truly want to live in and return to, and to succeed at that we must feel connected to the characters.

The head of the TV pilot testing consultancy I worked at bought one book for nearly everyone who worked there: Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The book identifies a “monomyth” structure that identifies common threads in stories all across cultures, and it has a reputation in part for its influence on George Lucas and Star Wars. Like any “theory of story” that is widely adopted, it can be used in tired ways by unimaginative risk-averse people to create dull art, and people in the creative industry hoping to achieve a kind of raw self-expression can resent it, but it’s a great place to start with Story.

That said, while Joseph Campbell’s anthropological approach is deeply researched and broadly applicable, it can also be unwieldy; I find that the practical wisdom of writers themselves can be useful. To understand Story, I tend to look to people who have been effective at captivating me in stories that also have published thoughtfully on their process. And at the risk of pigeonholing myself as a specific kind of person, the two monomyth-aligned creator-analysts I look to here are TV showrunner Dan Harmon and science fiction author Kurt Vonnegut26. And so when introducing people to Campbell’s “The Hero’s Journey”, I tend to prefer to introduce Dan Harmon’s gloss, “The Story Circle”.

The story wheel is read like a clock, starting with a character (“You”) who has a need (“Need”). The specific insight I like here is that the first job of every story is to get a viewer to identify with the protagonist. As for how writers work this magic, I’ve always liked Kurt Vonnegut’s “eight rules for writing fiction” as a toolkit -- specifically the three rules that are character-focused: #2, #3 and #6. They speak to a character’s success at being relatable, motivated and vulnerable.

By these rules, a creator can achieve “soulbinding”; a good story will get you in the shoes of its protagonist(s) fast, activating your mirror neurons. If you can get the audience to fall in love with your characters, the rest of the story doesn’t even have to be that interesting. We can tolerate a great deal of dullness from those we love.

There is a classic situation writers can complain about, where they get a note from a production executive that asks them to give their main character a dog. In this situation, DO NOT GIVE YOUR CHARACTER A DOG. This is a hack move. Executives are not experts in how to write; they are simply experts in how they feel when they read a story. They are telling you they don’t feel connected to your main character. In business culture, it is generally frowned upon to just say you don’t like or get something, so instead people try to be solution-oriented; this is also a decision insecure people make to avoid flat out saying “they don’t get it”. But many executives are ill-equipped to resolve a problem, bringing characters to life is the explicit domain of the storyteller.

When you read about the May Day Martyrs, you don’t feel like they need a dog to be captivating. The people of the world fell in love with the Haymarket Eight in large part because they presented themselves as remarkably relatable, motivated and vulnerable.

Relatable: “[Someone] To Root For”

Relatability is admittedly a bit of an annoying concept, but the basic idea is that a story should have at least one character that a viewer or reader can connect with.

Vonnegut’s Rule #2

“Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.”

The Haymarket Eight are a diverse mix of characters that allow anyone to step into the story and feel connected.

As labor movement icons, it was probably most important that they cover different ground professionally. The Lay Preacher Fielden worked in textiles; the Bombmaker Lingg was a carpenter; the American Idealist Parsons was a government employee. Indeed, despite their anarchist philosophy, a number of them are actually business owners. Old Toymaker Engel of course owns his toy store; the Understudy Neebe is a shareholder in the collective that publishes The Alarm and The Arbeiter-Zeitung. Lay Preacher Fielden specifically jokes in his autobiography that when he bought his own horses to operate independently as a teamster he “became what Chicago Tribune calls a capitalist”.

Their biographies also are diverse. At the time of the affair, Young Lingg was 21 and Old Engel was 50. Religiously, we also see a mix of perspectives common to Europe at the time. Schwab begins his autobiography talking about his Catholic Bavarian upbringing, whereas Fielden talks about his service in the Methodist church. Their politics are also very broad. Even just from the four hanged men we get three different definitions of socialism and anarchy. It invites a broad coalition to see themselves in the story of their martyrdom.

Motivated: “Every Character Should Want Something”

This is relatively straightforward, and I think it’s clear that the May Day Martyrs were deeply motivated. Those motivations strong enough to be felt shared by their global audience.

Vonnegut’s Rule #3:

“Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.”

They were motivated in different ways, but all wanted to see America live up to a promise of freedom. The Old Toymaker Engel wrote in his autobiography about his conversation with a dissident after arriving in the US: “I sang the praises of this ‘free and glorious’ country. […] I told him America was a free country, anybody could earn good wages if he wanted to, and save money besides.”

This motivation of seeking a better life was widespread and relatable at the time. Europeans in the 1800s were weebs for America as an idea. Seeing the Haymarket Martyrs betrayed by the country they crossed an ocean for pushes a shift from fandom to fear, leaving the international public disillusioned with the state of freedom in the US.

Vulnerable: “Be A Sadist”

When a person watches another person experience some sensory scenario, their brain will create similar patterns as if the event was happening to them; this phenomenon is said to be caused by “mirror neurons”. The more intense the experience, the more intense the connection. This motivates the third of the Vonnegut rules that apply to May Day Martyrs’ story.

Vonnegut’s Rule #6:

“Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.”

It’s a trope to achieve this by just killing a character of meaning and this is often hacky. And it can be problematic how often male protagonists demonstrate their vulnerability by killing a female character. But then Pixar will make the opening of Up where they do just that and people will be like “greatest opening ever”. So it’s hard to say what will or won’t break through.

Some of my favorite examples of this find creative ways to trigger multiple examples at one.

Walter White caught moonlighting at the carwash and getting made fun of by his students in the pilot of Breaking Bad, showing his vulnerability in a way that also highlights his broadly relatable motivation to earn more money.

In Train to Busan, we are introduced to protagonist Seok-woo as he gifts a Wii for daughter only to be told he gifted her one last year, showing a moment of weakness and framing his core motivation for the film.

The Battle at Lake Changjin, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army unit that we follow is early on bombed from above on flat open ground, leaving them defenseless and vulnerable.

On page two of Stephen King’s writer’s guide On Writing, he tells a childhood story about being wasp-stung and the dropping a cinderblock on his own foot crushing his toes; this is explained makes no sense for a book on writing, except its demonstration of his deeply human fragility deepens the reader’s connection with him as a narrator of his memoir.

Because I’ve watched Edge of Tomorrow many times (mostly on planes), I’ve seen Major William Cage die horribly perhaps thousands of times, an incomparable display of vulnerability which makes me deeply and tragically soulbound to Tom Cruise.

The shoeless John McClane of Die Hard is vulnerable and motivated to find shoes.

The May Day Martyrs demonstrate their vulnerability early in their autobiographies listing out their childhood traumas. Fielden loses his mother when he is 10; Spies loses his father when he is 15; Lingg loses his father when he is 16. Schwab and Engel both are orphaned at 12 years old; Parsons is orphaned at just 5 years old. Their struggles to find decent work in a rapidly industrializing world stack atop social disruptions.

Their many trials and tribulations show not just their humanity but their strength to strive amid strife. In hard times, they offered hope that hard work could lead the way to success.

When many movies are star-driven, the writing doesn’t necessarily have to do much “soul-binding”; you’ve already attached yourself to the protagonist by seeing their trials in prior films (even if as other characters). But for stories without stars, the narrative does more work. And since the May Day martyrs were not yet stars before their history unraveled, their emphasis on relatability, motivation and vulnerability was particularly important.

2.) Concept: “It’s The Gospel Meets Serial”

While the characters are critical to retain an audience, the audience first must be drawn into the narrative. Today’s film industry relies heavily on marketing to draw in prospective filmgoers, generally spending as much on selling the movie as they spend on the movie itself; for a story without attached talent, though, it is the concept that draws in viewers.

The go-to book to understand Concept in the early 2010s when I worked with a story consultancy was Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat; looking at the wide range of consulting tools and workshops on their website, I get the sense it is still popular (and consequently rejected by certain artist types). The most succinct expression of the concept is the “logline”, which is a brief pitch intended to spark interest in the full story.

Snyder has four rules for a logline: (1) it must be ironic, (2) it must imply the story in full, (3) it must make an investment case to producers, and (4) it must include the (“killer”) title.

“The Haymarket Affair” is a title that seems deliberately designed to disengage, so there is a clear failure on the fourth criterion. And Snyder’s third criterion is more directed toward screenwriters trying to get their script optioned, so telegraphing factors like potential audience and production budget can be consequential.

The core irony in the May Day Martyrs logline is clear though, and to capture both the irony and the arc of the narrative in a sentence, you could write something like this27:

A group of tradesmen pursue freedom across the ocean to the “Land of the Free”, where their practice of free speech, free association and free assembly result in their arrest, imprisonment and state-sanctioned murder.

This kind of irony is perhaps trite for a modern American audience, and I’m certainly framing things from a particular angle and reducing complexity, but this is what would draw a reader in. Readers would want to understand how and why America, a place famous for choosing freedom over tyranny, would be so hostile to the immigrants who share its dream.

Who Is Heisting Whom

The book Save the Cat also breaks down stories into specific story archetypes; with the Haymarket Affair, we are looking at a “Golden Fleece” -- a reference to the 8th Century BC myth where Jason and his team of Argonauts engaged in a journey to capture this particular amber-hued pelt. The fleece is a proto-macguffin in this three-millennia-old ancestor to the heist film.

The three essential elements Snyder identifies in a “Golden Fleece”28 story are (1) a road, (2) a team and (3) a prize. The road does not have to be the paved sort. In the Haymarket Affair, the literal journey of metaphorical trials is rather the metaphorical journey of a literal trial. The team is evidently the defendants, made a distinctive cohesive unit seemingly only by the trial itself. The prize is the Eight Hour Workday that the May Day demonstrators were marching for. The workers are trying to reclaim a pre-industrial independence of working life that political and technological shifts have taken from them. Its heist movie is a heist of justice and freedom.

It’s not essential, and actually somewhat rare in Hollywood films, that many protagonists will die in an STC “Golden Fleece” story. Nearly all of the Argonauts in the original myth make it to the fleece and back home. But as you already know, the Haymarket protagonists will all pass on years before the Eight Hour Day prize is won.

Ingredients of a Tragedy

Roughly half a millennium after the times of Homer and the age of the Argonauts, Aristotle would also write his own theory of narrative in Poetics -- much older than Save the Cat or Harmon’s Story Circle or Vonnegut’s Eight Rules for Writing but still very useful today.

In particular, he provides a series of elements that contribute to tragic “mythos”, a term generally translated as “plot” but relevantly also a cognate of “myth”. We find many of these within the story Haymarket Affair.

Peripeteia: a reversal of fortune

As already discussed when distilling the Haymarket Affair to a compelling logline, the grand reversal here is seen in the core irony of immigrants coming to the US to find freedom and instead being imprisoned.