X-Axis, Take The Wheel

A case for a dashboard-driven media diet.

In an ideal world, this newsletter helps people answer one simple question: “What should I put in front of my face?”

And the main way I’m answering this question for myself this year is: “Dashboards”.

In case that’s not intuitive, I’ve broken down my reasoning into ~25001 words. The case for a dashboard-centric media diet has three sub-arguments.

A great deal of unhappiness in high-income countries derives from a lack of meaning.

Much media erodes our sense of meaning through misalignment, inaccuracy, and incomprehensibility.

Building your media diet around a well-designed dashboard will invigorate your sense of purpose and wellbeing.

I’ve been spending my January developing just such a dashboard that I can quickly use to orient myself each day, and I think others could also benefit from a similar approach.

Let’s dig into the argument.

The Insufficiency of Wealth Alone

Claim: Happiness requires purpose, and purpose requires accommodation.

The draw of Americans on both the left and the right to more centralized leadership styles seems to surprise and upset a lot of people, but it’s not particularly surprising to me.

As someone who runs a daily global wellbeing survey, I’m maybe less surprised than most.

Academics are divided on the best way to evaluate wellbeing, but one popular framework is “eudaimonic wellbeing” which focuses less on emotional state and more on essential qualities of one’s life. It draws on Nicomachean Ethics, where Aristotle posits that what makes a thing “good” is how well it serves its function. (A good chair, for example, supports weight and can be sat in at great lengths; a good blog post is one that is comprehensible and shares useful insight.) A good life, then, is one that helps you realize your human potential -- what he calls “eudaimonia” and is often translated as “human flourishing”.

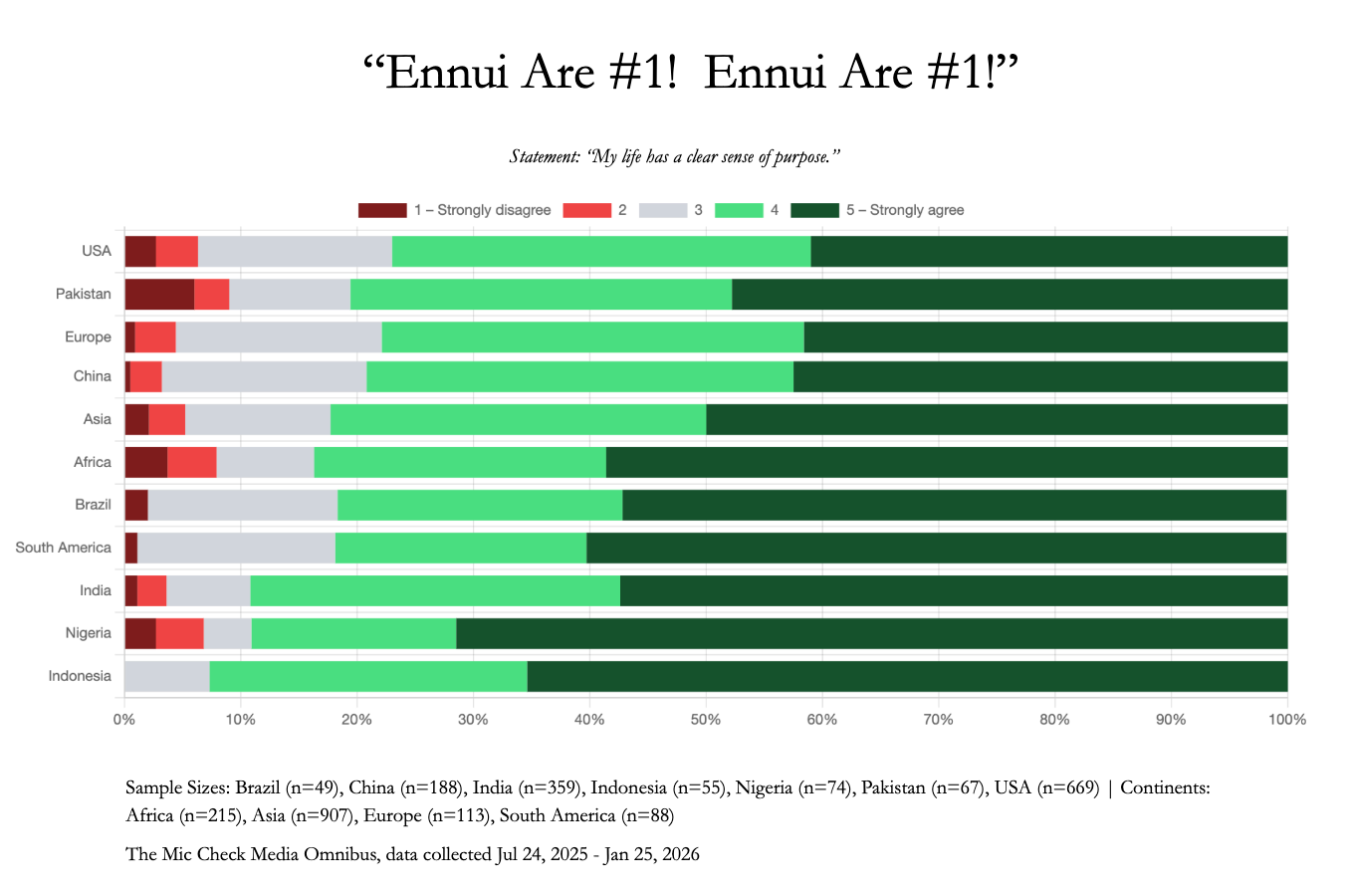

Psychologist Carol Ryff distilled this concept into a six-factor model of psychological wellbeing, and my daily survey asks people around the world to evaluate themselves on each aspect: Autonomy, Mastery, Growth, Relationships, Purpose and Self-Acceptance2. And when it comes to Purpose, the US is currently dead last3.

Meaninglessness is a serious problem. You don’t want to feel meaningless. You don’t want your neighbors to feel meaningless. You don’t want leaders chosen by people who feel meaningless.

The increasingly pro-authoritarian politics of our era are sometimes called “post-liberalism” -- a reference to how these attitudes are a response to perceived failures of conventional “liberal”4 politics. Some see liberalism as having centralized power in the hands of an elite few, failing to distribute and check power as it had promised. Others, though, have found that when people are given the freedom to choose their own sense of meaning, they are not always effective in locating it within their lives.

This post-liberal attitude is not exclusive to the left or right. Two quotes that articulate this perspective from both sides come to mind. They both have drawn criticism in the past year.

On the left, Zohran Mamdani critiqued the liberal order as dispassionate when he spoke of “the warmth of collectivism”. This was not a call to celebrate command economies and the camaraderie of breadlines. Rather, it voices a hope for a spirit of shared meaning and belonging, a sense of meaning that can be lost even in the most theoretically efficient of market machinery.

On the right, Donald Trump attacked the same market efficiency when he suggested that children have “two dolls instead of thirty dolls”. It’s harder for me to clarify the positive alternative here -- different people have different interpretations -- but my most generous read would be an endorsement of more local supply chains, which are less alienating for workers than the large globalist economic system we have today.

Since I myself am a globalist with liberal sympathies, I don’t totally align with these perspectives. Yet, I feel the tug of post-liberalism, and I too want to take seriously the problems of loneliness, alienation and meaninglessness.

I can at least agree that the path to shared meaning is not through more dolls.

It’s through dashboards. (Obviously.)

And to move further toward that case, we should first establish a rubric to evaluate current media on.

Three Ways the Media Makes You Sick

Claim: Healthy media is aligned, accurate and simple.

The “media”, from the Latin for “middle”, helps you center yourself in the cosmos. In an older time, “the media” was the view out your window and conversations with your neighbors. Later, you might leaf through a delivered newspaper. Later still, some would tune into a morning news broadcast with a focus on traffic and weather. Now when we wake up, we have seemingly limitless options. All designed just for us, intelligently serving us content!

Yet it’s not necessarily the good news that it seems. Last year around this time, I published a newsletter that was very focused around how you should be careful about letting the media shape too much of your values and goals, where I talk about this at greater length.

You want to know what to do, and a well-designed media will quickly provide what you need. An ideal media product serves as a Guiding Ontological5 Digest. Or to abbreviate it blasphemously: a GOD.

Let’s break down the three components.

Guiding. Your media should guide you. Which means it knows where you want to go, and is designed to get you there. You need confidence that it is aligned with your interests, not pushing its own agenda.

Ontological. Your media should also ground you. It should be real. It should be honest. It should make you aware of the world as it is, and help you avoid “The Screen Door Problem”: running into obstacles that you don’t see.

Digest. Your media should distill its subject matter, taking only as long as is necessary. It is comprehensible and brief. Murder is wrong in large part because it deprives a person of their time. Good media avoids such murder. It respects the sanctity of life.

How do our existing media options fare on these three dimensions?

Guidance: Does This Media Take Me Where I Want To Go?

Our media is increasingly trying to sell us things. It used to be that media would sell us things dispassionately, allowing space and time to be carved out of programming. With referral codes and digital ad tracking, publishers are increasingly invested in the effectiveness of their advertising.

As time goes on, the entire experience will become more and more oriented around getting you to part with your hard-earned cash. Their success is your maintaining employment and delivering your paychecks to their advertisers, a perpetual near-impoverishment.

Ultimately, it’s very rare to find media products produced by others that are aligned with your interests. And even when you find such a media product, its interests tend to drift against you in the long run.

Ontology: Does This Media Help Me Connect With Reality?

The view presented of the world in the media is inherently distorted6. Over 8 billion people live twenty-four hours each day, and there’s no way to cut that down without drawing blood. The trick is to find a distillation that captures the broad essence of the nuanced and complex story.

Narrative journalism centers anecdotes and asks you to generalize; it is very easy to warp a worldview with this strategy, selecting a convenient subject for your story. (Perhaps this is why the CIA was so committed to nurturing it.) Though many claim the classical Aristotelian narrative approach is universal7, it is indeed not the only approach. The dramaturg Bertolt Brecht sought deliberately to design his plays to distance the viewer so they could see the whole scope of the system at work, not merely a seductive story. I feel like Bertolt Brecht would have liked dashboards.

The notion of media bubbles and bias is certainly not novel for me to point out. I am emphatically adding, though, that this is a distinct challenge from merely misaligned interests. The media industry, if anything, attracts a disproportionate number of caring and empathetic souls. There are deep wells of good intention. The challenge is that understanding a big complex world is difficult, and while fact-checking a politician’s quote is straightforward, fact-checking a broader model of the world is more complex8.

Digestibility: Does This Media Respect My Time?

Digestibility is perhaps the worst of all. Our media platforms seek more and more time from us; our time is their lifeblood, and they need more and more each passing year to support growth. Great stories often center unresolvable ironies, as perfect resolution allows us to move on.

Even when brevity exists, it’s fleeting. In 2009, I subscribed to a newsletter called The Slatest because my two college best friends both recommended it; it was thoughtfully designed to give you the top 10 stories of the day without requiring you to click out into their ad-laden site. I would read it and quickly feel my news appetite satiated in about ten minutes. It was a great product but a terrible business model. A couple years later, the newsletter was repurposed from news aggregator to “a news companion”; instead of summarizing the news, it would direct you to more news. (And more ads.) Alas, good media is often bad business.

Thus, we have a media environment that is ungrounded, misguided and endlessly complex.

But what the market will not provide, we can learn to provide ourselves.

And joyously, dashboards can be as simple to create as they are to view.

Happiness is a Line-Going-Up

Claim: A self-designed dashboard will serve you better than generic media.

Back when I would interview for jobs, my work with dashboards was one of the first things I would talk about. I deeply enjoy all aspects of them -- decisions around what to place where, how to operationalize complex ideas succinctly, how to create a stable data pipeline that speedily provides needed insight, all of it. I’ve created them to help a wide range of folks: Hollywood studio execs, a multi-billionaire philanthropist and my dad. I suspect the most impactful dashboard I ever made was a bar graph generator used by TV networks selecting shows that would be watched by millions of people9, which was in my early twenties. (Personally I preferred the biplot generator, but after a decade of biplot-boosting, I’ve come to understand that most people just don’t feel the way I do about them.)

What I had never really done, though, was make a dashboard for myself.

I make decisions too. Sure, they are much lower stakes than “what TV series should be blasted out globally” or “what world-problem-solving startup should receive investment”. I control neither a giant media conglomerate’s programming department nor immense tech boom wealth. My main resource is my time and attention. They too are precious. And further, they are under threat.

In the mid-2010s, when I would lay my fingers at the keyboard in a web browser, I’d find my fingers moving on their own. I didn’t realize it at first. My left pointer would gently and independently tap the “f” key, which was enough for my browser to auto-complete “facebook.com” and draw me into the original endless feed.

I almost can’t believe I would struggle so much with Facebook, as someone who now just logs into it once a year when responding to birthday messages. To discover this pattern, I conducted my own self-ethnography, tracking my minute-by-minute time-use for roughly a year. All I knew at the time is that I was seriously struggling with productivity. The day would fly by, and I wouldn’t have a good sense for where the hours went. It didn’t make sense to me.

I didn’t have a dashboard for this data, and indeed I recorded this information by hand in Moleskine notebooks. To find my lost time, I simply would reread the events of the day. It was enough to help me realize I needed to break off of Facebook and approach media more skeptically in general, but there are easier ways in our great golden age of LLM-assisted rapid software development.

In working on a dashboard truly for myself, I understand why others have enjoyed them. The clarity they provide in a world so muddled with ambiguity. The personalized specificity of purpose. The gentle directive, stable and nourishing, with supporting data points where necessary. Some metrics that respond directly to my moment-to-moment activity, showing me I have agency in this world. Other metrics are unpredictable, reminding me that there remain mysteries unsolved that I must continue to pursue in noble faith.

This too is a kind of “post-liberalism”, I think. A decision to create my own straightforward purpose, and march forward in consistent rhythm. It is a kind of “post-liberalism” that doesn’t require structural changes, only the decision to make plans and follow through on them.

I’m confident that centering a dashboard will make me productive in a world that seems hungry for good work. It will also make me connect with constructive energy in a world that seems deeply lost and miserable. But a dashboard alone won’t ensure my productivity and energy are directed toward good. How do I do that? How might you also do that?

Here, it matters what you measure. Though any line-going-up can feel sacred, not every line-going-up truly is.

What do I want to measure? What do I want to achieve? These questions are critical in maintaining alignment, groundedness and simplicity, and I’m set to finish January with a working proof of concept that will guide me through the year.

Join next week when I’ll share how I’m using these concepts to ground my life in meaning -- no post-liberal authoritarian drift required!

I was told readers of mine are using AI to summarize these essays, so I’m making more of an effort to focus each one on a particular topic. If they are still too long, please just tell me; if they feel too short or rushed, you can tell me that too!

If you group “autonomy/mastery/growth” into a wellbeing of agency and “relationships/purpose/self-acceptance” into a wellbeing of accommodation, you get an active/passive binary that maps to the values I identified in the world’s major value systems.

The survey system is still a work in progress, and larger sample sizes will allow for more weighting and cleaning of the signal, but that’s the data as it falls out right now.

Liberal in the more general sense that largely would reflect traditions of the Republican and Democratic parties: a value for checking executive power, divided branches of government, democratic elections, and so on.

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. Good media doesn’t have to be factual, but it should enable you to connect with and/or engage in reality. Bad media deludes you, leaving you blind to both the risks and opportunities in your midst.

To be clear, I’m not saying that the media directly states mistruths. I do believe there is great effort to avoid blatant misrepresentation of facts. It is more that the attention economy is not designed to help people develop accurate mental models of the world.

I believe that classical narrative is universally resonant, but that’s not the same as being ontologically honest. This is in part what can make it dangerous.

I have a specific epistemic model in mind, but for the sake of brevity that will have to wait for the next newsletter.

How much these tools actually are used to shape decisions versus mere politics is hard to say, and there is certainly a strong chance my biplot tool served as mere “dashboard theater” as so many do.

A long time ago I audited my entire media diet with a spreadsheet and then wrote an article about it for a long-gone but once-influential tech website called GigaOm. The basic idea was to rank everything I read 1-5 and then think about where it came from and prioritize those sources more. I’ve thought about doing it again, but I dislike such processes seemingly much more than you do, lol