Globalism Is Too Hard. Can We Make It Easier?

Six Trips Around The World. My Screen Door Problem. The Many Humanisms of Yesteryear. A Dashboard Guiding My 2026.

I travel a lot for someone who doesn’t quite like traveling.

Truly, I’m much more a homebody who just so happens to not have a home.

I grew up mostly on a series of international islands, trying a few US cities post-college before landing in LA. I mostly kept put between the ages of 23 and 30, traveling a couple weeks a year for work. When I turned 30 in 2019, I realized LA would never feel like home, so I packed up all my stuff into a storage container and set out to broaden my sense of the world.

Since I found travel exhausting, I realized it would be easier to establish a permanent travel routine. I would use Newtonian principles in my favor -- the same inertia that was keeping me at rest could be keeping me in motion.

Six years into this journey, I’ve now been in motion for roughly as long as I was at rest. And traveling is tiring me out. So I’d like to stop.

But it’s not so simple.

I had specific goals when I started traveling. I wanted to understand the human experience in our time. And I wanted to have a more realistic mental model of the world. I’m not eat-pray-loving; I’m cultivating a better sense of species-being. And it just turns out cultivating a sense of species-being is exhausting.

Last week, I wrote about the joys of dashboards in general. This week, I’ll walk through the specifics of how I’m mapping my personal dashboard to my specific goals for the year. And again, this will break down into three parts.

The Big Problem of the World’s Bigness

Three Models For Tighter-Knit Humanity

A Dashboard That Might Help Get There

Feel free to just scroll to the dashboard screenshots at the end if that’s what interests you.

For everyone else: let’s start with the problem.

The Screen Door Problem

Over a billion birds die annually from flying into windows. As animals, we’re quite good at using our senses to detect risks and respond to them. We’re also good at knowing when we lack information; a bird wouldn’t fly full-speed in the pitch-black, for example. It would show more caution. But specifically when it believes one thing about its surroundings (it’s clear ahead) and the truth differs (there’s a window), the result is tragedy.

I mentioned in last week’s essay the idea of “The Screen Door Problem”, which is the risk one takes when they maintain a mental model out of alignment with the world. People don’t fly into windows, so it’s much more visceral and available to imagine a screen door. You or someone you know has likely not realized a screen door is closed and walked into it. It hurts. It’s no fun.

This is the problem I am trying to solve -- for myself and for people more generally. We cannot directly perceive the-world-at-large. I’ve tried. People say the world is small, but it’s not. To think it is small is to show one isn’t thinking at a human scale -- they are thinking of markets or nations or some other framework. And these frameworks are misleading. And when you take the largest capital city on each continent as a sample size, your worldview will be warped. This is how you can walk into screen doors.

We rely on media platforms to fill our gaps. They are our window to the world. But these windows have funhouse physics.

Many publications choose to just focus exclusively on local affairs. And this is good! Alone, it won’t ground your humanism in a global perspective, but placing more focus on your neighbors and community is sensible. Local media operations are important -- they are often under threat, so I’d highly recommend supporting one if you have the resources for it.1 (Not all local news brands do their own independent investigative reporting, though; some simply distribute national/global content. Try to find the former if you can!)

Others focus on that nebulous frame between the local and the global: national news.

Let’s do a quick analysis of what’s in the major papers today.

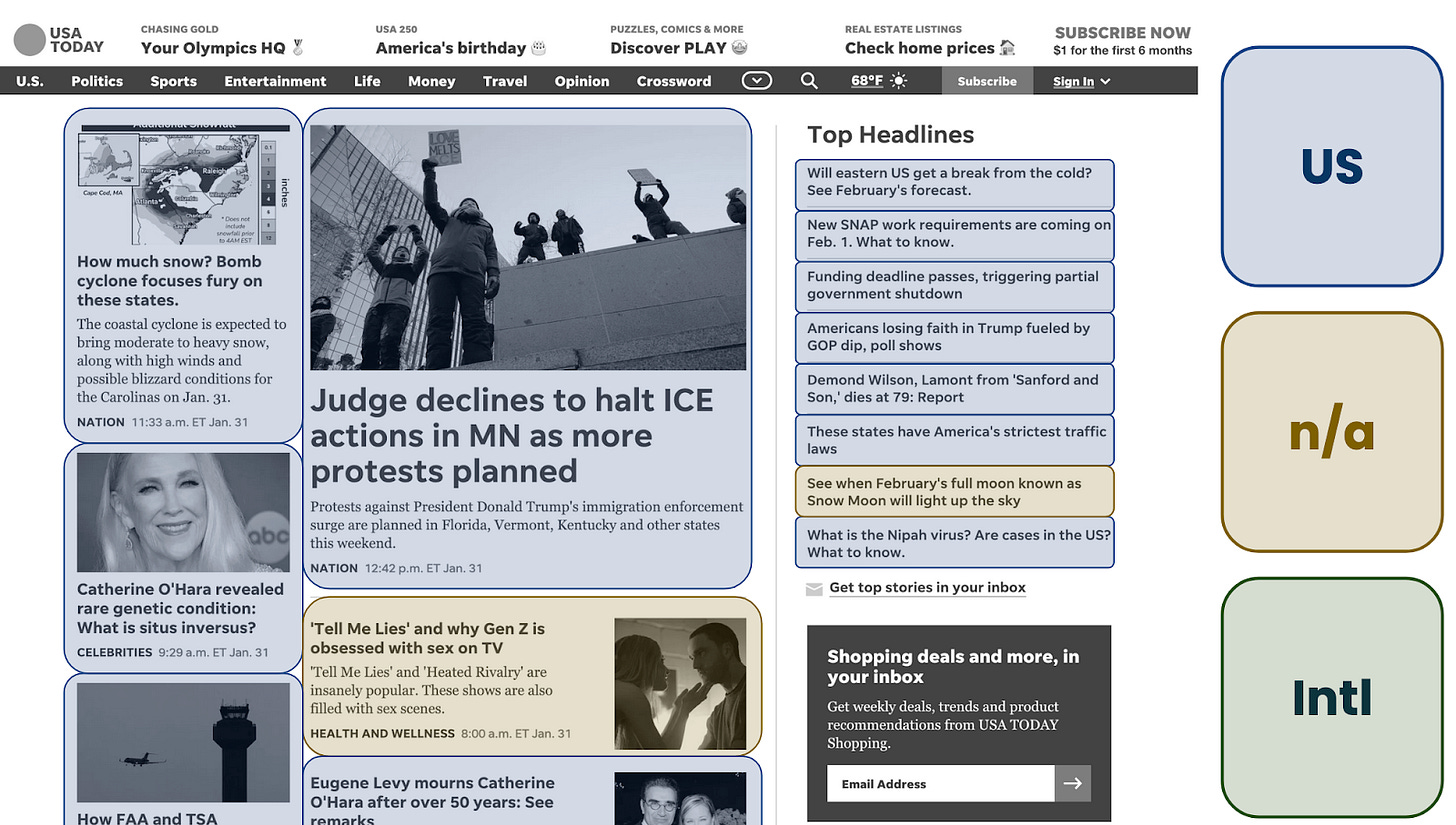

The “front page” of The USA Today website has 12 national stories and 2 stories I would classify as generic. I will never hate on a story telling people how to observe the Snow Moon, but it feels like a stretch to call it global. (It peaks at 5:09pm Eastern Time tomorrow, in case you were curious.) The other generic story feels roughly as broad as moon coverage: an article about young people’s interest in sex2. For stories that are non-geographic in nature, I’ve classified them as “not applicable”.

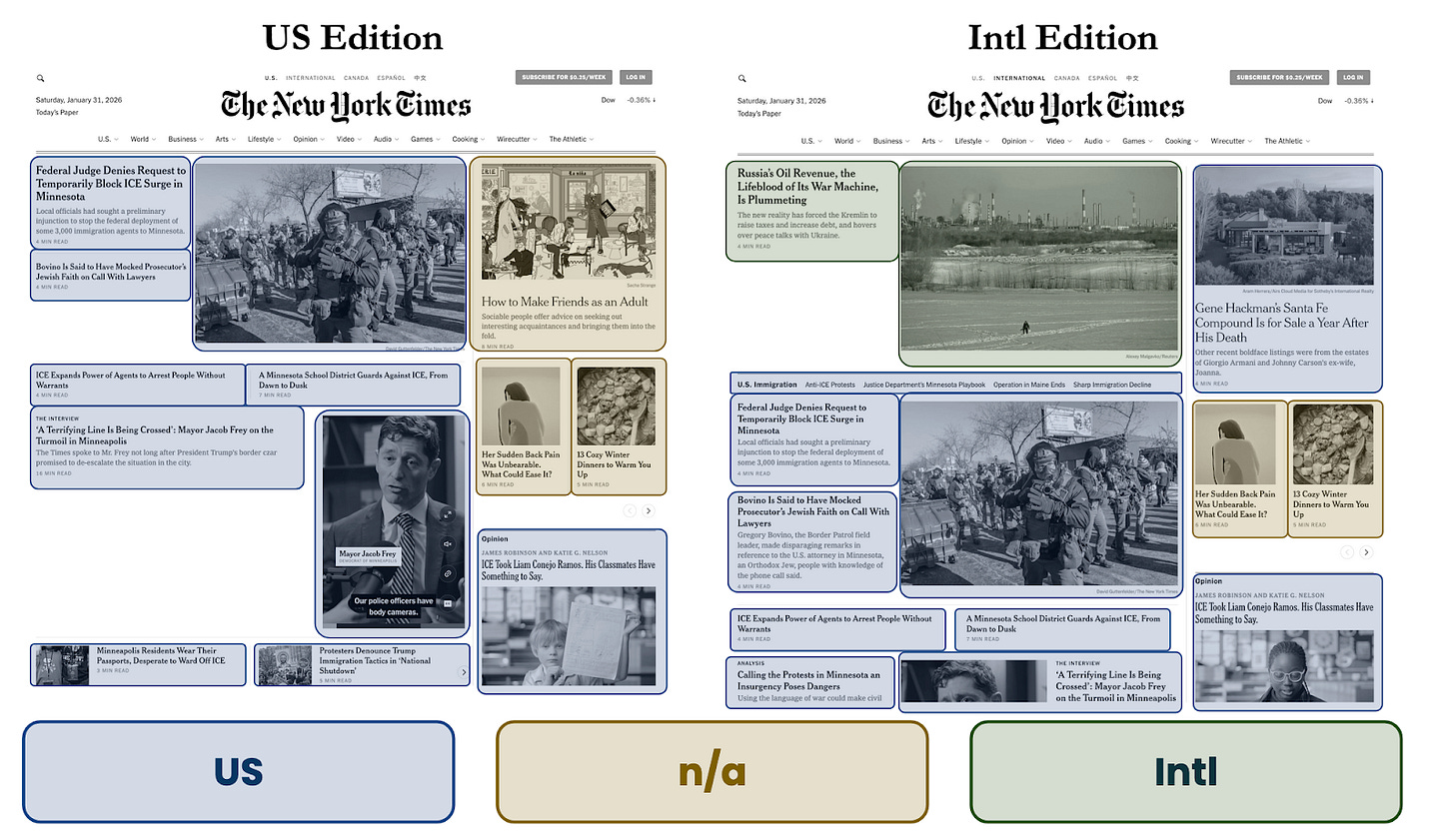

Meanwhile, the New York Times front page gives the choice between a US Edition and an International Edition. The US Edition today has 8 US stories, one with a picture and one with a video; it also has 3 generic stories -- about back pain, cozy dinners and making friends. International readers don’t need to learn how to make friends, it seems, but they do get a single international story and no sacrifice of US stories; there are still 8, plus 4 links to coverage of US Immigration excluded from the domestic edition.

It’s fair that at this particular moment, most international readers of American papers are reading them to monitor the collapse of democracy, and I expect a broader study wouldn’t be quite so US-centered. Further, the generic front page is not how people discover stories; they are being directed from social media or search engines, or subscribers are logged in and receiving curated recommendations.

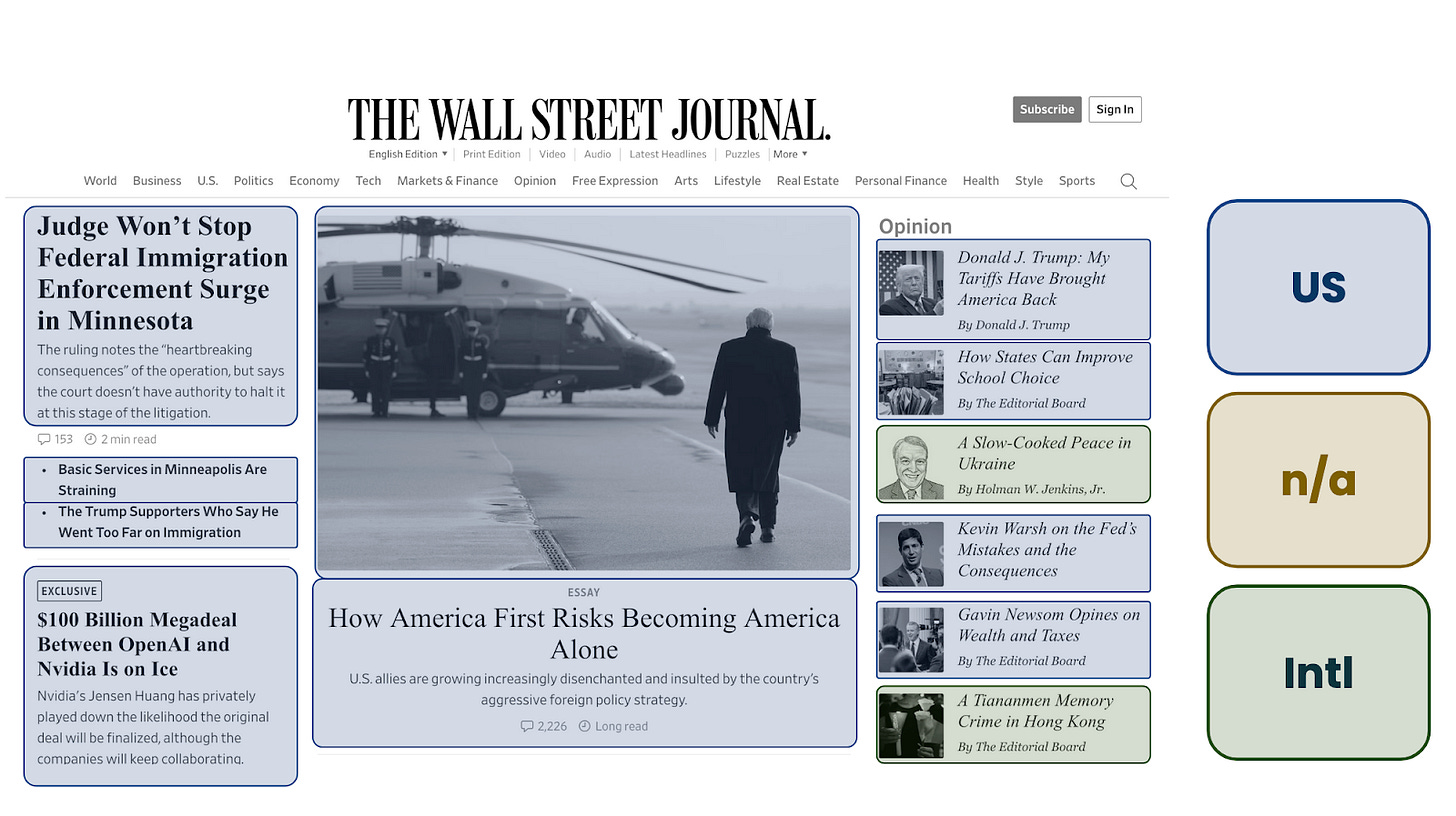

The Wall Street Journal is only marginally better. Of the big three American papers, it’s the only one with two -- count ‘em! -- international pieces above the fold on their website. They are opinion pieces rather than news, so I’ll leave it to your pre-existing biases to decide whether NYT’s hard news piece about Russia is more substantive than WSJ’s two op-eds about Ukraine and Hong Kong. The point is that “the world” that major US publications show us features surprisingly little of, well, “the world”.

People obviously draw information from different sources. But to extrapolate off of today’s websites:

The US occupies 82% of a WSJ front-page-reader’s mental world map.

The US occupies 88% of a NYT International Edition front-page-reader’s mental world map.

The US occupies 100%3 of a USA Today front-page-reader’s mental world map.

There are better English-language publications, thankfully.4 Let’s pick a smaller example that I think actually makes a strong effort to be global, as -- though certainly an improvement -- they still fall short from cultivating a representative humanist perspective.

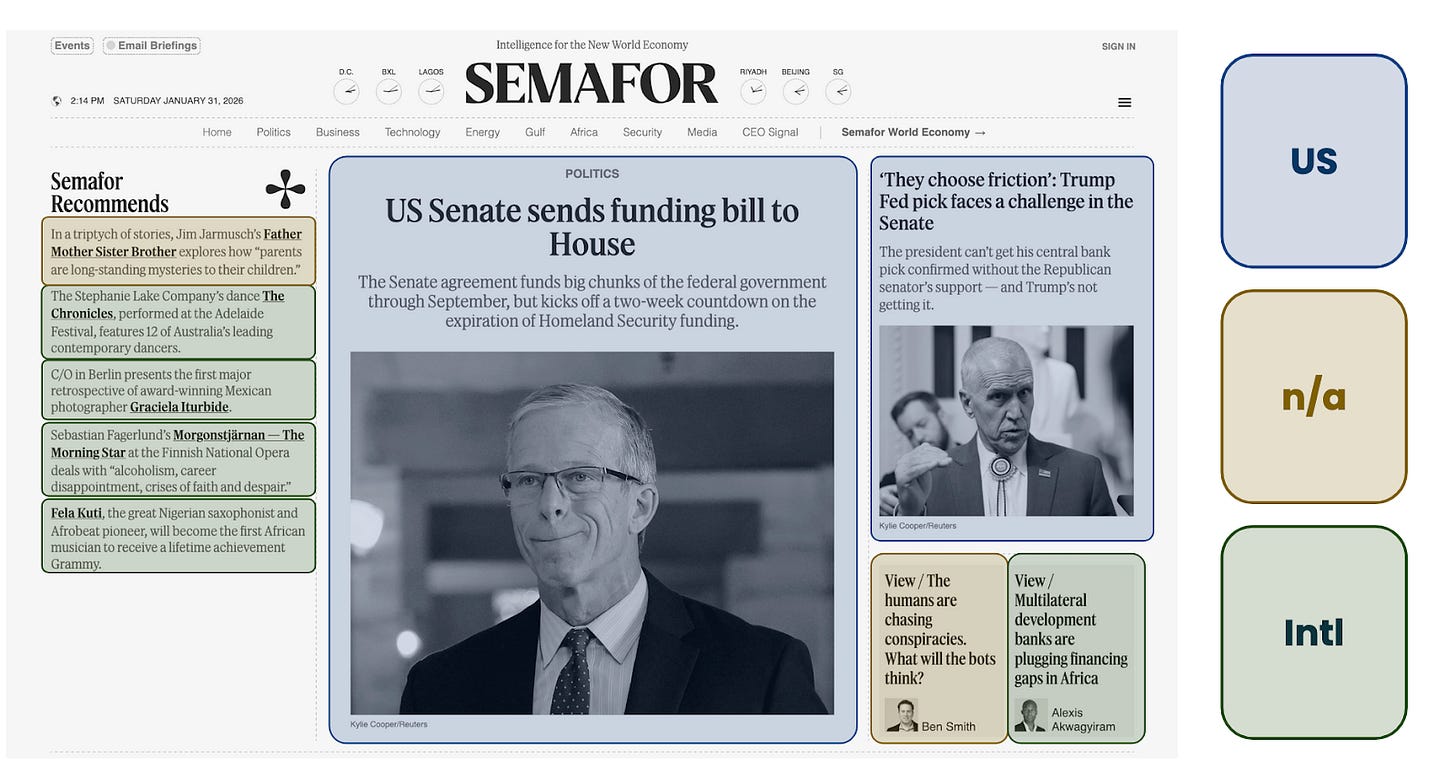

I’ve been subscribing to Semafor’s “Flagship” newsletter since it started in 2022. And though I will critique it, and I don’t read every edition, I do check in with it and want to give credit where (some) credit is due.

Let’s look at the front page first.

Only two US stories! With five international stories! (And two that are somewhat hybrid.) It invites Americans like me to contemplate that perhaps we are not most of the global population! Radical.

They are doing this in part by recommending content that they themselves didn’t author, but I think that is still wonderful -- so much of a brand is its curation power, not simply its creative capacity. Yes, 100% of the photos are driving attention to US stories; but with a tagline like “intelligence for the new world economy”, you know they expect that their audience can read. And look at all those clocks showing time in different places! Plus they plug Fela Kuti, who I had discussed in my inaugural 2026 newsletter “The Great Calendar Heist”.

The mental world map of the Semafor front-page-reader will be much less distorted than other American publications: only 29% of their location-specific front-page headlines are in the US.

This is getting warmer and closer to the truth, and they often perform even better within their newsletter.

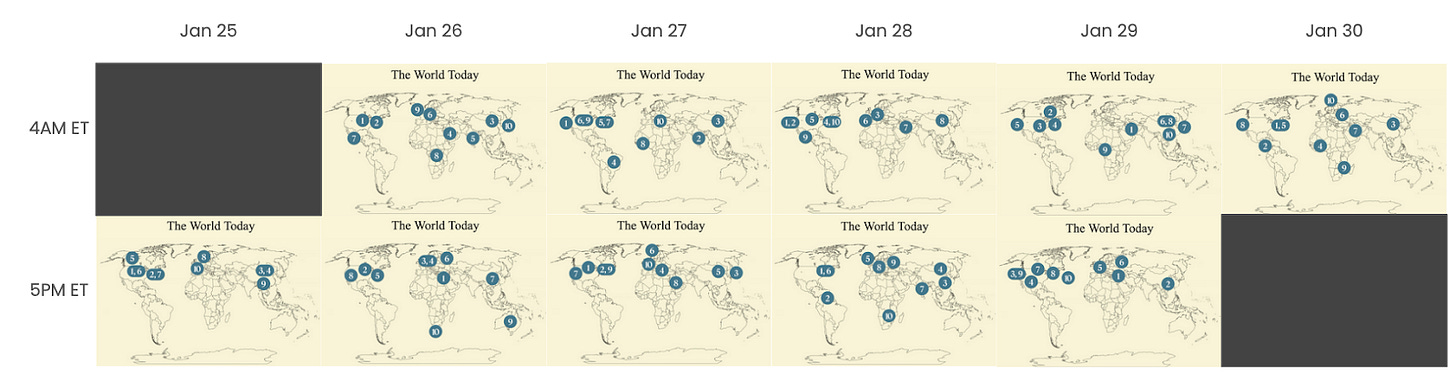

Their weekday morning newsletter is named “Flagship” -- with “flag” both referencing their “semafor” brand and also as a signifier of international scope. As a map-lover, I love that they situate each story within space at the top of the newsletter. It also makes it much easier to geographically analyze their coverage; they clearly are doing so themselves!

Let’s look at the past week of “Flagship” map summaries.

Of the 100 stories they featured in their newsletter during this week, 36 seem to be tagged as within the US -- but I think if anything they’re too generous in identifying stories as US-centric. For example, their January 30th headline “Apple’s Record iPhone Sales” is pinned to Silicon Valley reflecting the headquarters of the business, but those sales took place around the world (with particularly strong growth in China). After accounting for a few of these generic headlines, my math has them closer to 25 US-centered stories. Some days give as few as 10% of their headlines to truly US-centered stories.

Is this the clear-eyed worldview I’ve been looking for?

To answer that, I’d need to know some population statistics. What percentage of the world’s people are in the US? You probably know the global population and the US population, and you can do the division, but before you even do that -- do you have an intuitive sense of the US share of the world’s humans?

Hopefully you have a guess in mind. Or enough of a feeling that when you see a number you’ll be able to sense if it’s higher or lower than your expectation.

Ready? Here’s the number: the US contains ~4% of the world’s population.

Even the praiseworthy internationally ambitious scope of Semafor is over-representing the US by a factor of over 6X by my geographic assessment and 9X by theirs. A truly population-weighted newsletter would have a single US story in fewer than half of their ten newsletters they send in a week.

But nitpicking at Semafor is unfair; they are making a real effort to widen their aperture. Mainstream news outlets like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and USA Today overrepresent the US on their front page by ~2050%, ~2200% and ~2500%.

And so this leaves us with our challenge:

Lacking a true and grounded sense of the world is dangerous.

The tools available to develop that sense of the world largely mislead us.

Building that broad grounded sense of the world directly is unsustainable.

So what are our options?

How can we follow the broader human story of our time? What’s a globalist to do?

Fortunately, global humanism has a deep historical well that can guide us.

Globalism Is Old

Something I’ve enjoyed about the past two Januaries I’ve spent in Mexico City is the extra couple weeks of holiday decor. Many in Mexico, like in other countries of the Iberosphere, celebrate “Día de Reyes” -- or Epiphany as it is sometimes known in English.

I tend to study the Catholic Church primarily as a media company, maintaining and expanding its story universe. (I try to do so in a way respectful to my ancestors to whom it was sacred, as well as to the many who have been harmed by the institution and its affiliates.) The organization, in its desire to spread, would result in absorbing and incorporating local stories and heroes into their lore. This was often done with creation of new saints and saints’ days, and the tradition can be seen to continue today with the 2025 canonization of Carlo Acutis, deemed to be the patron saint of the Internet. This is a sort of aspirational globalism, and I think there’s perhaps something in here I can learn.

The Three Kings Day traditions similarly evolved over time, though in a seemingly less centralized fashion. There are records from the 700s discussing how the kings represented the three Mediterranean continents: Europe, Asia and Africa. Early depictions of the kings would often reflect the locality of the depiction; only in the second millennium, though, did art have the kings’ appearances reflect their distinct cultural heritages. It may be the earliest example of “diverse recasting”.56

I expect these celebrations were supported in Spain and other monarchies because it provides a framework to legitimize the role of kings within the otherwise radically liberal doctrines of Christianity. And the enhanced racial pluralism of the story was certainly resonant in the explicitly abolitionist Catholicism of Bartolomé de las Casas and his peers in the 16th century -- still centuries before the same movements would pick up steam in the northern Anglo-American colonies.

We can look to other models for global inclusiveness as well.

While visiting China last year, I came across the phrase 人类命运共同体 (“community of common destiny”) several times. The quote is initially from Hu Jintao, who served as Premier before Xi Jinping; Xi Jinping has carried the term forward, though, invoking the ties across nations and communities that bind us all together. We share the earth and therefore are partners in facing the future.

This Chinese notion of common destiny is grounded both in deep historical traditions, going back nearly three millennia to the 易經 (“I Ching” or “Book of Changes”), which was used to predict the rise of their Western Zhou dynasty. The idea was to build a framework to render the randomness of the universe intelligible, using a mixture of casting yarrow stalks and reading the stars. Two major Chinese schools of thought grow out of this idea that we can find our path within an ordered universe: Daoism focuses on the natural order, while Confucianism focuses on the social order.

Today, these ideas are still recognizable within the contemporary ideology of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. In 2020 I watched 领风者 (“The Leader”), a 7-episode donghua7 about the life and contributions of Karl Marx. The material was very new to me at the time, which gave it a dry educational feel. Still, it captures that Hegelian sense of historical inevitability, which is honestly present in most hero narratives. (The theme song samples “L’Internationale”, an expression of transnational human solidarity that serves as a counterpoint to the globalism of market capitalism.)

I came across a third distinct tradition around human connectedness traveling in India. A key part of Indian humanism emphasizes the connection of individuals with their meatstuff through mind-body connection -- in meditation, in yoga, in various oil-based therapies. This physical groundedness shares a bit with how the naturalism of the Daoist frame, but whereas Daoism focuses outward, these South Asian traditions focus inward. (Though both ultimately drive toward a dissolution of the inner/outer distinction entirely.)

But much seemed very distinct to me about how the subcontinent orients itself around pluralism. The easiest reference point for me here is what is sometimes called the “head bobble”. Whereas the West uses a vertical nod for “yes” and a horizontal shake of “no”, Indian head gestures operate somewhere between. The “head bobble” or “head wobble” can be used to say “yes”, “maybe” and even “no”.8

The Hindi word associated with the bobble is “अच्छा” (“āchā”). The term is often translated as “good” or “fine”, but etymologists postulate it is derived from the Sanskrit word “अच्छाय” (“acchāyá”) meaning “without a shadow” -- unshaded being brightly light, or evident/visible. The bobble can then be read as simply a motion that affirms a message is understood. It’s a sort of Vedic “roger that”.

This same nonbinary denotation exists somewhat in the word “okay”, which as an abbreviation for “all correct” both signifies adequacy (in signifying correct) but also lacking (in that it relies on improper spelling)9. It is both right and wrong at the same time. The draw of this irony is part of what makes the word one of the most common to spread outside English.

I personally call the head bobble “the quantum nod”: it conveys a superposition of “yes” and “no” in one discrete gesture.

What do we learn from this? How can we emulate these broad yet distinct traditions of connectedness?

I do think culture and media are critical to an effective globalist-humanist foundation. While we tend to think of media innovations as new apps or devices, there is just as much innovation in these examples: a holiday celebration, a practical theory of natural physics and an expression of body language. Whether it’s from the deliberate diversity of Día de Reyes, the shared journey of Daoist cosmology, or the pluralistic ambivalence of the quantum nod, these frameworks enable peaceful cooperation in groups of over a billion people.

And yet, to believe media can unite people is actually a bit of a “hot take”. The general consensus is that it tears people apart. Most of us can witness how media platforms are clearly polarizing the world now just through using the platforms, but this is nothing new. The printing press is seen as a major driver of the Thirty Years’ War, for example, in which pamphlet-driven religious fervor whipped the Germanic Holy Roman Empire into killing 40% of themselves.

It does not seem inevitable to me, though, that the media must be so destructive. It is somewhat of a paradox -- that in order to connect people, media must be between people, thus separating them. Even the mere creation of language creates an abstract layer that distances us from a simpler mirror-neuron empathy. The trick is to get media to support unmediated interactions, rather than having media replace it10. Humanist media brings people together; anti-humanist media drives people further apart.

Ultimately, the goal is to foster the humanistic spirit. Good media creates a foundation for discourse.

I’m not going to create a new holiday, cosmology or head motion, but I can help provide some light scaffolding to our existing media decision space. This is the project I’ve been engaged in since releasing my first post: The World Is Not Small. It provided a list of 80 tracks representing 80 groups of 100 million people on the planet the day the population hit 8 billion.

The World Isn't Small

Today humanity hit a new milestone, with the UN projecting a population size of eight billion people. Many are reflecting on what this means for resources on the earth, and these questions are valid and intereting. Personally, I’ve been more concerned about what this means for our abilities to care for each other.

While I think improving the world’s relationship with media is a critical challenge of our era, that’s out of scope for this year. What I can do, though, is work on improving my own media mindfulness. And the goal is to make purposeful11 media consumption easy and natural.

To do this, I am creating a dashboard.

A Dashboard To Guide Me

Having covered the sublime joy of dashboard meditation last week, I’m going to focus on the practical elements of how I’m mapping my goal of pushing myself toward a more humanistic media-consuming experience.

This will be a personal dashboard designed primarily to help me stay on track, so I won’t necessarily share every view here, but I will share some key data updates throughout the year. If I committed to sharing everything constantly, it would tempt me to posture rather than merely measure. While conspicuous consumption can be a positive motivator, I think an intrinsically motivated framework will be more durable.12 The goal is for the dashboard to be, in itself, useful.

There’s a criticism of modern politics becoming too centered on a “liberalism of manners”, more about learning the right words to say than about actually making substantive improvements to people’s lives. This critique resonates with me, and yet, as a media researcher, I do believe messages and images are powerful. Again, this is about The Screen Door Problem; everyone is better off when their sense of the world stably maps to reality.

There are many factors that drive one’s capacity to be mindful about their media diet, just as there are with one’s eating diet. I am trying to use my relative flexibility to focus my media environment to find easier ways to consume more whole-grain truth and less empty calories. I am almost certainly not measuring the right stuff yet. The purpose of this is to learn, and it is certainly not to create new rules and shame people. Hopefully that comes across clearly!

The dashboard I’ve designed focuses on three key categories: service, sustainability and systems.

Service: What value am I delivering to the world? What value is realistic for a given day?

Sustainability: What risks exist threatening my service capacity? What changes do I need to make?

Systems: How are my habits supporting or detracting from my global-humanistic mission?

I focused almost exclusively on developing professional skills and saving money from 2013-2020, and I focused nearly exclusively on media processes from 2020-2025. I’m hoping my dashboard design helps me balance these various objectives and ultimately act more directly in ways that help improve lives.

Service

Service will be more central to me in 2026. It is here that I hope to find my primary line-goes-up metric -- my “Global Ontological Digest” as discussed last week. I want to shift away from esoteric systems-tweaking and toward using these ideas to help the willing broaden their perspectives. I also want to share systems I’ve built for myself with others.

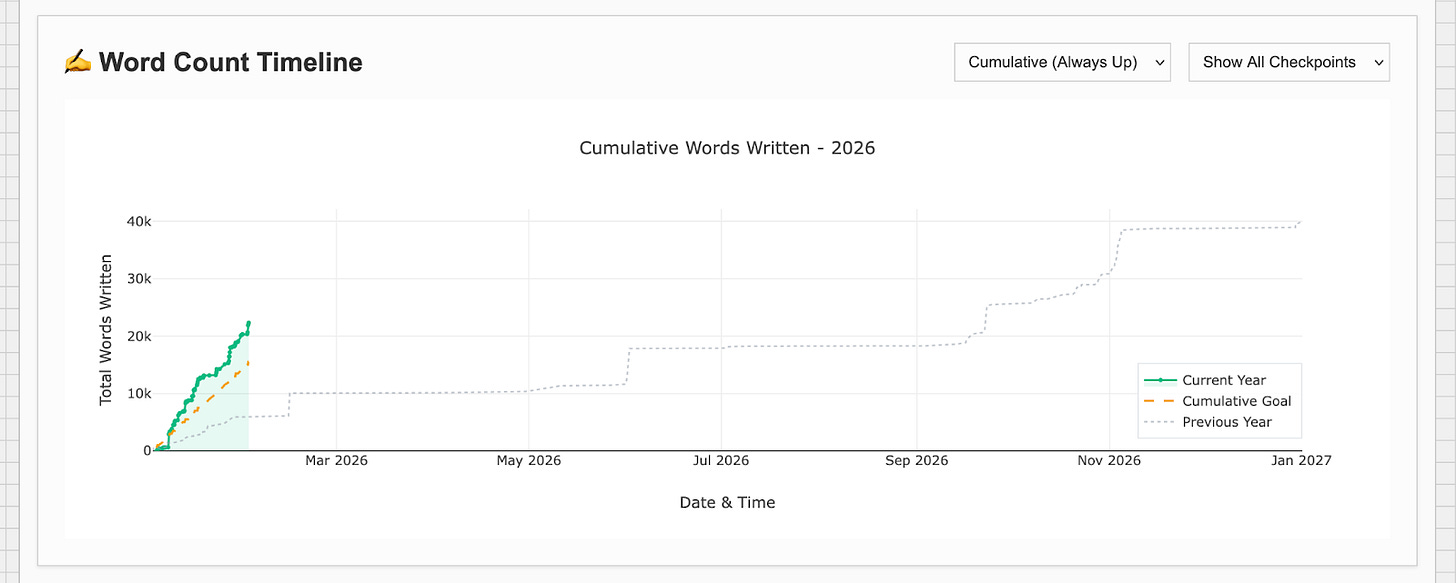

To express this, I’m really focusing on word count and making small incremental improvements each day. I think I should be able to write a post a week, especially as I try to integrate my other work into this newsletter. All my work connects to media and wellbeing, so it will hopefully be relevant to subscribers. Achieving my writing goals will mean withdrawing from much other socializing, so hopefully receiving the occasional graphs and reflections is a worthy substitute!

Viewing my word count timeline is quite nice. I am working on adding more tracking of the influence of media frameworks I am introducing, and I’ll consider that a major component of my service as well. I will also start making some of the tools that I use available to others, and tracking their usage and usefulness will be the primary way I assess my own personal success.

Stay tuned on that piece!

Sustainability

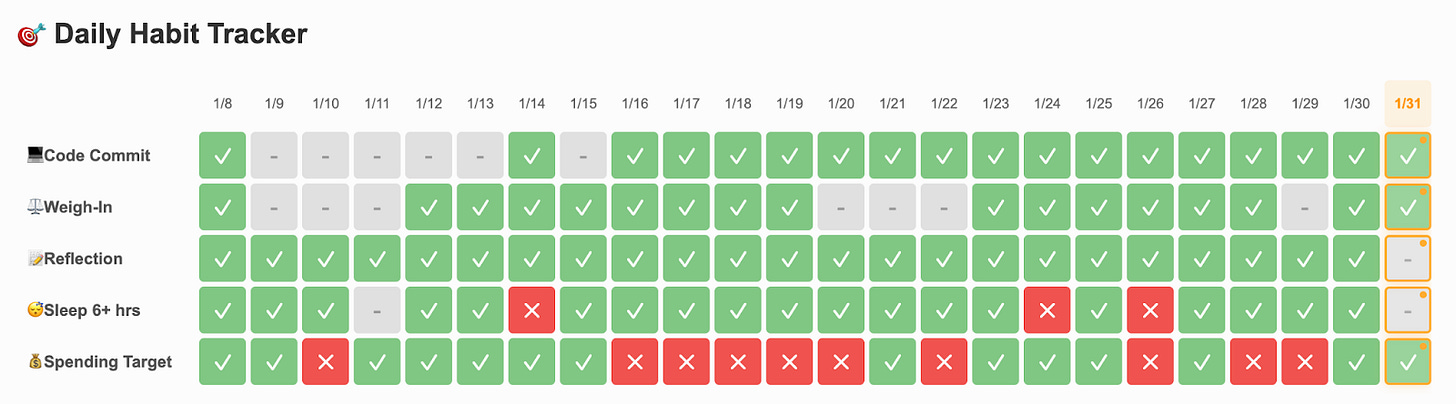

Sustainability is really more about keeping alert for “red flags”, so I think a tracker view works well here.

I track a mix of habits to confirm sustainability, and I expect I’ll grow these and even become more strict with time.

The major groupings here are around psychological, biological and financial risks. Am I maintaining an emotionally healthy working relationship with myself? Am I introducing unnecessary health risks in my eating and sleeping? Am I operating at a budget that reflects my economic condition?

Though I know pursuing immortality is currently trendy, I see permanent sustainability as fundamentally impossible and undesirable. But on the ephemeral-sustainable spectrum, I’m hoping to moderate my position.

Systems

I generally think I’ve had the habit of over-investing in my systems, but this is also central to the work I’m trying to do.

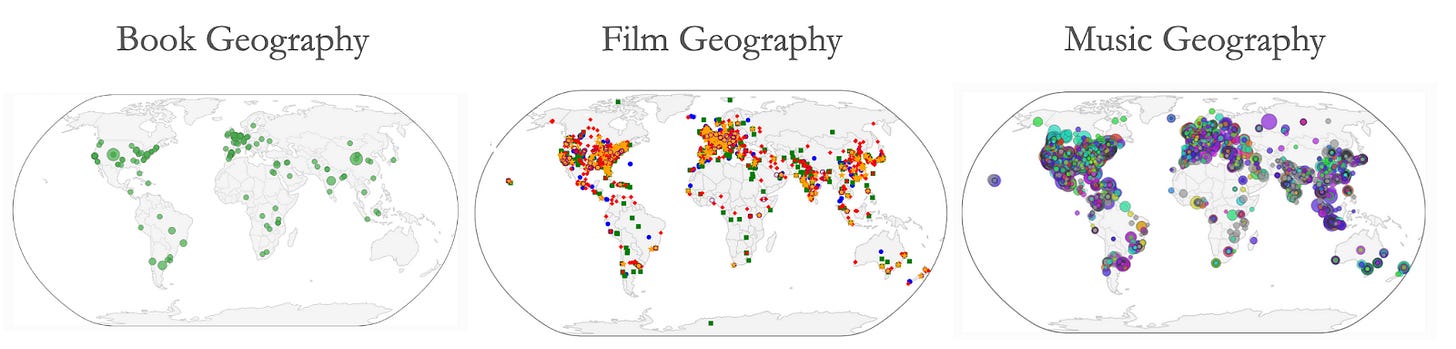

It is here where I put my own media habits under the microscope, and try to understand how I’ve been performing so far and where my major gaps are. I’ve started by mapping the subjects and origins of books, films and musicians within my diet.

The largest weakness across all three formats is on the African continent, so this is a place I’ll need to pay more attention to this year. This will take some deliberateness, but I’ll also try to tweak the design of my life to make this more natural.

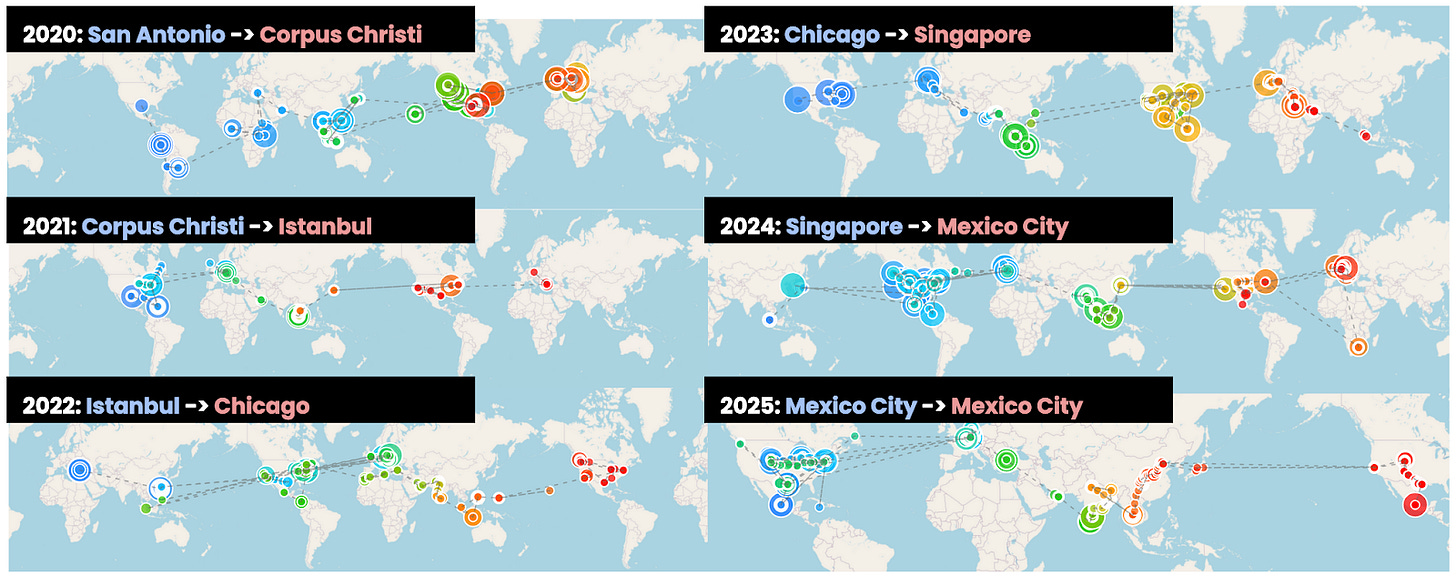

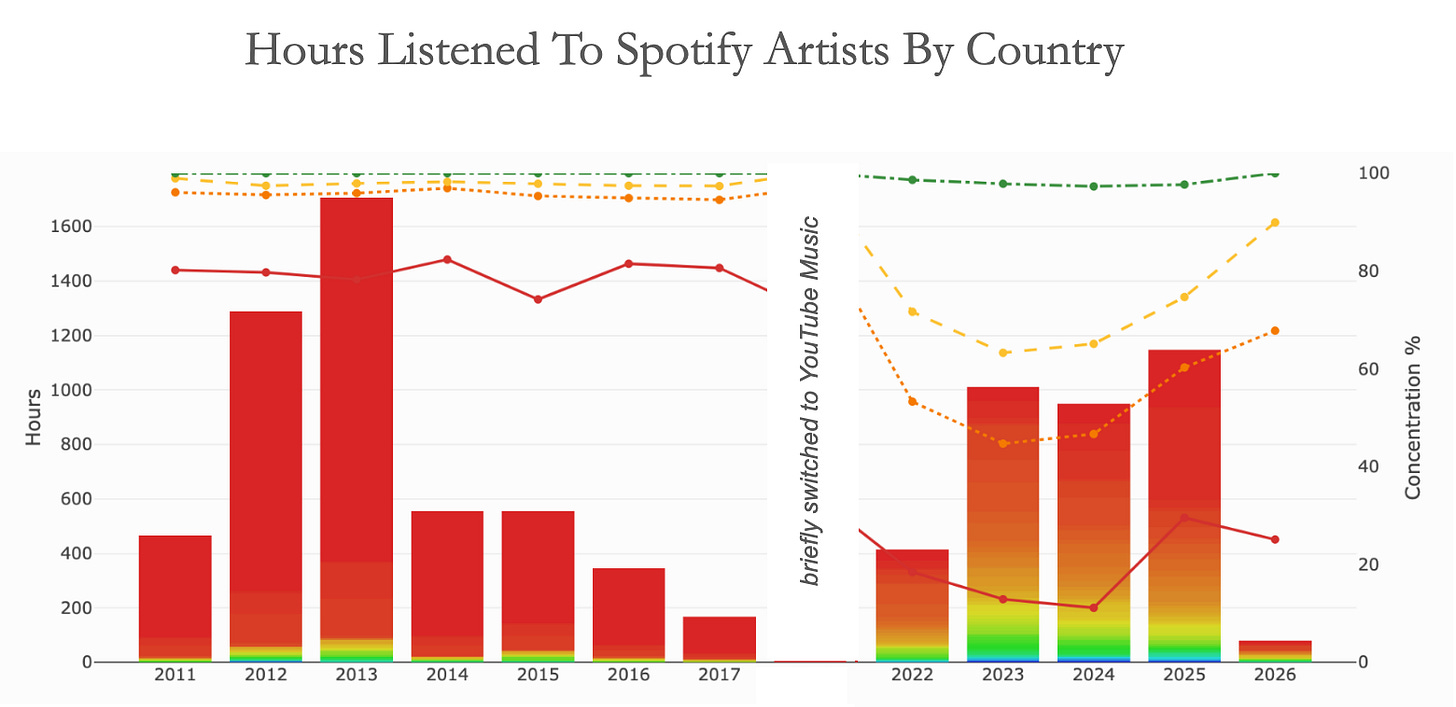

To investigate how the global aperture of my music listening has evolved, I downloaded my Spotify data and used a mix of Perplexity and OpenAI to collect and validate information about the countries of origin for music I listen to13. And indeed, I can see that decisions I made in 2019-2020 to listen more globally did result in a more diverse geographical taste profile.

This chart is a little tricky to read, but the bars stack various countries by hour of listening; the most listened to countries are dark red and the least listened to are later in the classic ROYGBIV spectrum. The more rainbow you see, the more diverse my listening. The four lines correspond to the percentage of my listening from my top country, top five countries, top ten countries and top fifty countries. 2024 had the lowest percentage of listening to my most listened-to country, corresponding to a sort of personal “peak woke” for me.

My music spread was thrown off a little last year, with my most-listened-to country breaking over 20% and my top-five most-listened-to countries tipping over 50%. I think this is in part because I listened to more songs recommended from friends this year, which tipped me a little outside my globalized focus. Music is an important tool to connect with neighbors and one’s local community, so this is permissible. This year, though, maybe I can find ways to both embrace global creative works while also being engaged with communities of meaning to me.

An Era of Unprecedented Media Agency

As we enter into this era of vibe-coding, your decisions about media won’t just be what platform or channel to use. You can already, in a brief amount of time, design your own agent-driven newsroom.

I am hopeful that these less human-intensive media pipelines can still be humanistic in intent. And in fact, they can perhaps even be more humanistic than options available pre-AI. You can create a media that better balances the concerns of people globally -- one that is better insulated against the various anti-humanistic forces that infiltrate our information pipelines.

Maybe you’re skeptical that taking this kind of control is worthwhile. Indeed, creating this system wasn’t as point-and-click as recent viral Claude Code projects seem to have been. It’s taken much of my time and focus, not to mention about half the credits provided with my Cursor Ultra subscription.

A question I return to often is: if my media sources weren’t representing the world accurately, how would I know? When would a blind spot become obvious to me? How can I try to detect such a blind spot before it poses a risk to me? It seems like there are enough fundamental misalignments in my media environment that building this audit framework was worthwhile, and this framework will be easy to repeat and update on a quarterly basis.

This dashboard will be the center of my media usage in 2026, and with a few charts and graphs keeping me honest, I’m confident I can work toward a more humanistic information-gathering experience — even if only within my own media diet.

Maybe you can even find one on Substack!

They include non-news stories like this to be salacious enough to draw clicks while staying within their brand guidelines. Don’t fall for their tricks.

This is shock-jock math already, working off small sample sizes, but I’m excluding the content that is neither international nor domestic in these calculations. Yes, Catherine O’Hara was Canadian-American, but her passing took place in the US so it is at least part of a domestic story. Maybe all stories about media personalities should be classified as generic. It doesn’t change the fundamental point.

I personally try to draw from a mix of The Economist, Al Jazeera and The South China Morning Post. All three have strong international coverage, but operate from different parts of the world: London, Doha & Hong Kong. They also have different funding models: The Economist is primarily subscription and privately owned (about a quarter owned by the Rothschilds); Al Jazeera is a public media foundation funded by Qatari petro-wealth; and South China Morning Post has been owned since 2016 by Alibaba, a tech giant under Chinese Communist Party oversight. They are all anglophone and in places where the British have played significant roles, but enough history has passed that I do think they offer distinct perspectives; if I am deliberate, I can try to fill in gaps and learn new things. (The particular biases of these publications are worth getting into in another newsletter.)

There can be no deification without “DEI”.

Movie pitch for a gender-swapped Epiphany story: She Three Kings.

Donghua is the Chinese version of anime; literally, “motion painting”.

There are sources for this online like the BBC here or Wikipedia, but I’ve also experienced all three meanings personally. To me, the bobble was used in agreement more than it is used for disagreement, but I think this is also because the people I met were generally agreeable, not because the gesture has an embedded valence.

There are a wide range of etymologies of “okay”, but this one is my favorite.

Markets, as currently constructed, encourage the creation of media platforms that isolate people and replace unmediated socializing. I do not think all market designs would drive this outcome, though.

The current state of algorithmic media delivery is very purposeful as I understand it; its purpose simply is not aligned with my purpose.

A brief caveat as well: While the dashboard has been helpful, it’s also been a bit of a transition. When I started using it, it was actually so unsettling it gave me a bit of a panic attack. If you haven’t been tracking your goals and feel like you’re on track, looking at a dashboard of key metrics for the first time can be a rude awakening. Like, looking in the mirror for the first time in years and realizing you don’t look how you thought you looked.

I’ll share more on this pipeline in a future post!